Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:00 — 38.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

During the 1970s, the modern-era of ultrarunning was slowly increasing. The term “ultramarathon” (“ultra” for short) was introduced by legendary Ted Corbitt about 1957 and by the early 1970s it was being used more often to make the distinction with the public that athletes could run further than the marathon distance.

During the 1970s, the modern-era of ultrarunning was slowly increasing. The term “ultramarathon” (“ultra” for short) was introduced by legendary Ted Corbitt about 1957 and by the early 1970s it was being used more often to make the distinction with the public that athletes could run further than the marathon distance.

100-mile races were not yet widely prevalent and open to all, but the spark had been kindled to bring back the distance that many hundreds of runners had achieved before World War II. The shorter ultra-distance races including 50-miles were ever-increasing, including races such as the JFK 50 in Maryland, the Metropolitan 50 in New York City, London to Brighton in England, and the Comrades Marathon in South African. Many other ultradistance races were put on around the New York area by Ted Corbitt and various point-to-point ultras were raced throughout Great Britain.

| Please consider supporting ultrarunning history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

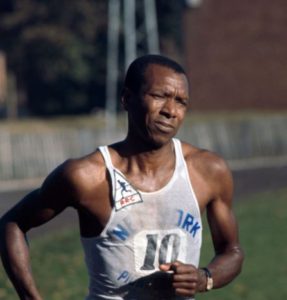

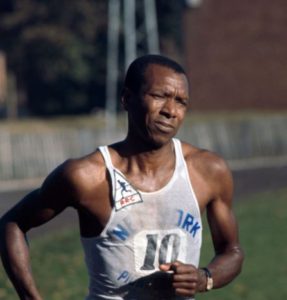

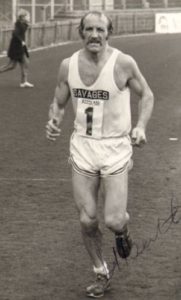

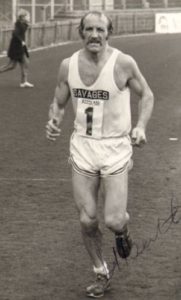

Ron Bentley

The Tipton Harriers

While home on leave, he watched Jack Holden race in the area. That motivated Bentley to train harder and he went on weekly long runs of about 10 miles. Once out of the service in 1951, he joined the Tipton Harriers, wanting to concentrate on long-distance running. He participated in many races but didn’t start racing the marathon until 1958 when he was 29. He placed third at the Midland Marathon at Baddesley with a time of 2:47:18. Bentley became one of the core leaders of Tipton’s cross-country and road running teams which developed into the most successful club in England. Ron’s voice could always be heard above all others shouting encouragement for his team.

Ben Nevis Race

Bentley ran a classic trail race in Scotland for many years, the “Ben Nevis Race.” It was only about 10 miles (depending on the route taken) but ran to the top of Britain’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis (4,406 feet), and back down. It was said, “It is not an unusual sight to see exhausted runners carried off to the hospital.”

Bentley’s Early Ultrarunning

The Exeter race included 3,000 feet of climbing along the way. It was the 7th year of this race, usually won each year by “The Ghost Runner,” John Tarrant. But Bentley broke the course record by about three minutes with his win. Tarrant experienced a disappointing slump during the race and did not finish. Alcohol had always been a part of Bentley’s training. He explained, “It’s what you did. The night before I won the Exeter-to-Plymouth, I had three pints of Whitbread and steak and chips at an Inn.”

1971 Century of Miles

1971 Radox 100 Mile Race at Uxbridge

With Bentley’s failure finishing the 100-miler two years earlier at Walton-on-Thames, he made sure he was ready for this second attempt. For many months he had been training 120 miles per week including back-to-back running days on weekends with four hours on Saturdays and five hours on Sundays. “If the Tipton Harriers clubhouse was locked when he got back, four pints of beer and three bottles of lemonade would be waiting for him in a bucket by the back door.”

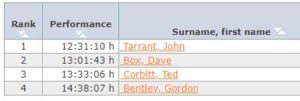

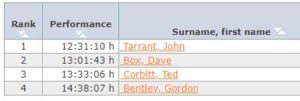

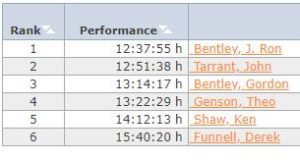

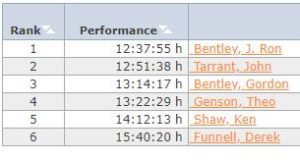

Twelve runners were entered into the highly competitive 1971 100-miler including the “ghost runner,” John Tarrant, age 39, the former world record holder who was allowed to race in Britain. Phil Hampton (1935\-) of Great Britain who had recently broken the 50-mile world record on a track with a time of 5:01:01 was also in the field along with Bentley’s brother Gordon. The two brothers prepared the night before the race drinking pints of ale and eating stake and chips.

The Start

The next morning, just minutes before the start, Tarrant was making a last-minute bathroom stop and having a crisis of confidence. “In the toilet I tried to instill in myself the importance of the race, why I had more incentive than any other runner to win.” His family was there to support him and he promised himself to give it all he had. He made his way to the start with must seconds to go.

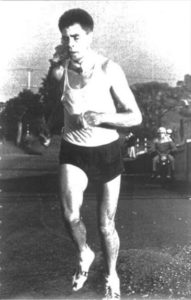

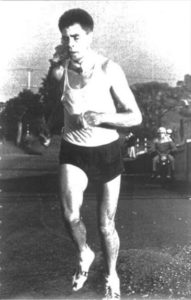

After the start, Ron and Gordon Bentley when out strong. After ten miles Tarrant had fallen back. “Tarrant wasn’t running, he was wallowing like a stricken ship, and after twenty miles he’d fallen six minutes behind the leading pack. Ahead of him he could see Ron Bentley running alongside his older brother Gordon. Tarrant was still struggling at 30 miles and was telling himself if he didn’t feel better after one more mile that he would drop out.” He said, “I was flogging my body unmercifully.”

The Second Half

Others were struggling too. Ron Bentley had a seventeen-mile lead over Tarrant at mile 60. He said of Tarrant, “I had seen him leave the track, but when he came back, he was flying. I just couldn’t believe the way he was running. One minute he’d been dying and the next he was lapping me and I was starting to lose my confidence.” Bentley broke the 100 km British record with a time of 7:29:07 but his lead over Tarrant was reduced to fourteen minutes at mile 70 and thirteen at mile 80.

Tarrant continued to push hard. At mile 90 the lead was six minutes and at mile 95, Bentley had only a two lap lead. “From dawn to dusk, for eleven appalling hours, he had floundered hopelessly behind the metronomic Ron Bentley. At last, as darkness hunched around them, he’d run his rival down.” The spectators were amazed at what they were watching. The race director, Eddie Gutteridge (1941-) recalled, “It was Tarrant’s greatest race. He was mortally ill. It moved you to be there, because he was not physically capable and yet his mental approach was magnificent.”

The Finish

Tarrant finished in rough shape with blue lips and froth around his mouth. He sat covered in blankets, barely able to speak. Bentley said, “I knew he was very ill, but there was nothing we could do.”

Two weeks later Tarrent’s recovery was slow and he was still too crippled to run. But a few months later he was back nearly to his world-class form. But soon his health degraded and it was discovered that he had stomach cancer. Initial surgery helped and recovered enough to continue to run. But during 1974 his health slowly worsened and he lost significant weight. He died in South Africa on January 19, 1975 at the young age of 42.

Ken Young

Young ran his first marathon in 1969 at the National Junior AAU Championships in Redfield, Iowa. He finished in 3:21. He ran his first ultra in 1970, a 50-miler at the National AAU Championships in Rocklin California with a time of 6:20.

While working on his Ph.D at the University of Chicago, Young joined the school’s track club where he met Ted Haydon (1912-1985) who was twice an assistant coach on the USA Olympic team. He asked Young to help him with statistics for a race to introduce the idea of handicapping. That started Young’s lifelong computer work with runner data. He could compare results from various distances to determine who the faster runners were.

In 1971 Young, working as a meteorologist, began a daily running streak of at least one mile a day that lasted nearly 42 years. In 1972, Coach Haydon set up a race to see if Young could break an indoor world marathon record. He set the world record in Chicago of 2:41:29.

Darryl Beardall

Beardall ran on Brigham Young University’s track team during the 1950s where he finished 7th in the national championship for the 10,000 meters. From his early twenties he consistently logged 120 training miles per week. He started competing in ultras at the age of 31 in 1967 and that year won the Pacific Association of the AAU 50-miler with 6:06:47. The next year he also won it in controversy with a time of 5:38:16 on a 5-mile road loop course at Sunset-Whitney Ranch in Rocklin, California. Skip Houk (1942-) actually won by 11 seconds but was later disqualified by the AAU because he didn’t display his bib number on his jersey, even though everyone knew who he was in the small race.

Beardall was also an elite marathoner and finished 23rd at the 1968 US Olympic Marathon Trials. He improved his 50-mile personal best to 5:18:55 when he finished 3rd in the National AAU 50-mile Championship in 1970, also at Rocklin, California.

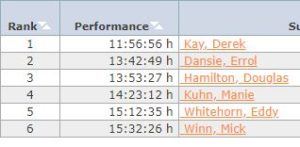

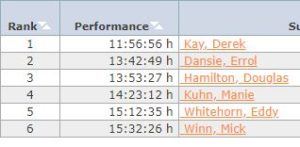

The 1972 PAA 100 Mile Race

Others who finished included Ralph Paffenbarger Jr. (1922-2007) with 16:42:58, and Paul Reese (1917-2004) with 17:15:34. Six other runners did not finish due mainly to the high temperatures (75-80°) and humidity during the race. Dehydration was common to all who ran. Natalie Cullimore won the 1973 edition of this 100-miler and in 1974, there were no finishers.

Young died in 2018 with 141,000 life-time miles. In 2020, Beardall was 84 years old and had run more than 300,000 life-time miles. He was still doing some running despite a hip replacement and lived in Santa Rosa, California.

100×100-mile Relay Record

The Baltimore Road Runners Club lowered the record on May 17, 1981 with a time of 7:53:52.1 on Towson State track. This record was held for 16 years. The average time was 4:44.1 per mile.

Derek Kay, the first to break 12 hours for 100 miles

1972 Western States 100-mile March

In the spring of 1972, at Fort Riley, Kansas, Captain Joseph McCarthy was on an adventure team consisting of many Vietnam veterans still in the service. His wife had ridden in the famed race a few years earlier and he came up with the idea to have members of his adventure team try to be the first to cover the Western States course on foot instead of on a horse.

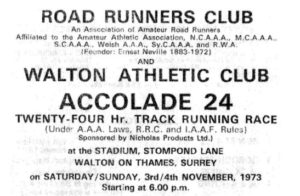

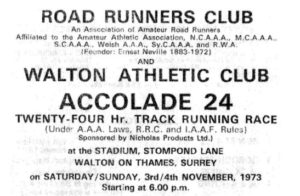

1973 Walton-on-Thames 24 Hour Race

Wally Hayward of South Africa still held the track 24-hour world record of 159 miles, set in 1953 at Motspur Park (see episode 61). But little did they know, on October 23, 1972, George Perdon of Australia reached 164.9 miles in 24 hours at Albert Park in Melbourne during an uncertified road race, going four more miles than Hayward.

Pre-Race

Sixteen runners entered, but John Tarrant had to withdraw because of his serious battle with cancer. Joe Keating (1948-), age 27, was the pre-race favorite because of his recent win at London to Brighton.

Ted Corbitt enters

Corbitt had a very long trip to England, grounded in Germany because the British airports were completely fogged over. But he finally arrived. Because the start wasn’t until 6 p.m., he did his best to rest during the day for the hours before the race. Outward he was calm, but inside he was in turmoil.

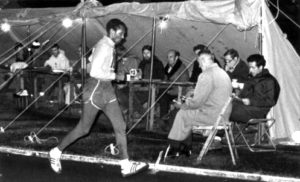

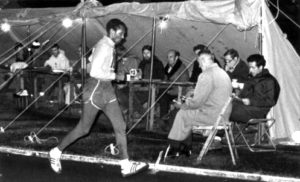

“We set up tents along the back-straight until the track resembled an army bivouac area. Each tent contained a bed in case a runner was so exhausted that he needed a complete rest and a portable stove for brewing tea and actual hot meals. In front of the tents were littered bottles and cans filled with home-made food and drink preparations. There was also a medical tent. The timer’s tent dominated the front straight. It was large accommodating 15 timers, one for each competitor. This tent glowed yellow-green under the harsh lights of several Coleman lanterns.”

The start

Before the start, the fifteen runners gathered together in a small dressing room where they joked, laughed and seemed totally relaxed. Bentley sat in the middle of the room and dominated the proceedings with his jokes and rough humor. Keating sat in a corner giggling. The casual pre-race atmosphere calmed Corbitt’s jitters.

The runners were called to the track at 5:50 p.m. and Corbitt joked, “How are you supposed to warm up for a 24-hour run?” The weather was cool and wet and the command “Go!” was shouted. Gordon Bentley shot into the lead at 6:15-mile pace followed by Ron Bentley and Keating who were chatting. Corbitt was content to run near the rear.

After three hours, Gordon Bentley had nearly reached 25 miles, with Ron a half mile back, and Corbitt two miles back. During the fourth hour one runner threw up repeatedly and another was seen badly limping. Corbitt stopped for a meal of a hard-boiled egg, and a cup of orange and pineapple juice. Bentley fed on soup, rice pudding and cups of tea. His crew fed on a bottle of whisky.

The midnight hour was described as, “The silence of the track was ghostly. The only regular noises were the padding paces of the runners as they wove their way through the dark night.” After six hours, Ron Bentley led and hit 50 miles at 6:08:11, two minutes behind the world record pace. Corbitt was 41 minutes behind in 4th place. Half of the runners were struggling badly including Keating and Gordon Bentley.

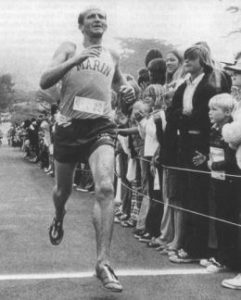

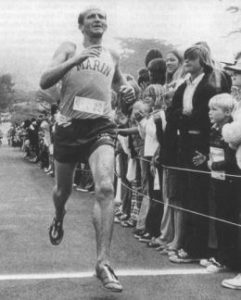

By the ninth hour, Bentley had a five mile lead and was seen “threading his way through the traffic jam of walking, limping, dog-trotting men.” He was in command and seemed to be a machine.

The Second Half

Bentley recalled, “That’s when the real battle started. I’d got a pull in my right thigh, the left foot was painful and I was slowing. I tried to convince myself I could still break the record even if I had to walk it, and every lap was one less to do after all. I slowly got on terms again.”

A British masseur took Ted into the dry dressing room and tried to bring life to his thighs. He bundled up in a dry sweater and headed out again as the rain finally stopped.

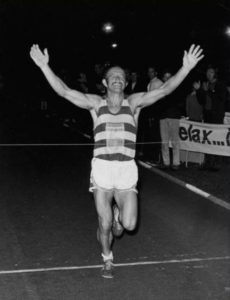

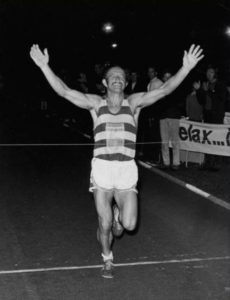

The Finish

During the afternoon the stands were filled with cheering spectators. An announcer continually counted down Bentley’s laps which greatly annoyed him. He pled, “Tell them to stop going on about the record and I will smash it for them.” (with a few swear words added.)

The remaining battle was for second place. Corbitt had held it for 13 hours but with 30 minutes to go, Peter Hart (1938-) was within two laps of him. “The track was a madhouse. Fans and handlers clogged the track, making an obstacle course for the runners.” Corbitt’s crew pled with him to go faster, but it was useless. He had nothing left and with 20 minutes to go, Hart passed Corbitt. Then the gun was fired and the nightmare was over for Corbitt.

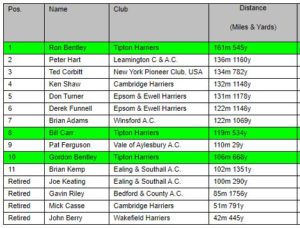

Bentley reached 161.3 miles, and new world track 24-hour record. Hart reached 136.4 miles, and Corbitt, 134.6. Eleven out of the fifteen starters remained at the end. Corbitt was carried off like a “rag doll” to a hot tub where he and other runners lay for a half hour. He was then lifted out, dressed and driven to the place he was staying. He later said, “That was my most disappointing result. Maybe I waited too late in life. Maybe it was just the accumulation of stress.”

“Those that had run knew the part they had played in a momentous event. Those that witnessed it were left marked by the resolute nature and personal performance of each of the competitors. Goodbyes were eventually exchanged but the ‘unspoken’ probably told more as each one their bid their personal farewell.”

Ron Bentley died in 2019 at the age of 88.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Sports Argus (England), Aug 27, 1960

- Bill Jones, The Ghost Runner: The Epic Journey of the Man They Couldn’t Stop

- Birmingham Daily Post (England), June 3,5, 1971, Nov 5, 1973

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Mar 12, 1972

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), Mar 13, 1972

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Mar 12,13, 1972

- Ron Bentley Recollections & Memories

- “Western States 100 on Foot: The Forgotten First Finishers.”

- “40 Year on: Ron Bentley and the 24 Hour World Record” 4 parts

- John Chodes, “Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner”

- Daily Mirror (England), Nov 6, 1973

- Tipton Harriers

- Darryl Beardall

- Northern California Running Review, Feb, Mar 1972