Podcast: Play in new window | Download (37.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Several 100-mile races and solo runs were held in 1974 across the globe that year, but the most significant run, which mostly went unnoticed at the time, was performed by Gordy Ainsleigh in the rugged, hot mountains in California. You were probably told he was the first, but he was actually the 8th to cover that trail on foot during the Tevis Cup horse ride and the sport of trail ultrarunning was not invented that year.

Previous to 1974, more than 1,000 sub-24-hour 100-mile runs had been accomplished on roads, tracks, and trails. Thus, Ainsleigh’s run did not get much attention until several years later, when with some genius marketing, it became an icon for running 100 miles in the mountains, the symbol for Western States 100, founded in 1977. Using this icon, they inspired hundreds to also try running 100 miles in the mountains on trails.

Also hidden in the annals of the Western States Endurance Run history, is a forgotten story of 53 individuals, men and women, who covered the Western States Trail on foot in 1974, just one week after Ainsleigh made his famous run. This was another story that was well-known at the time but wasn’t mentioned in the Western States origin story. Perhaps, it isn’t significant, but it is interesting and will be shared.

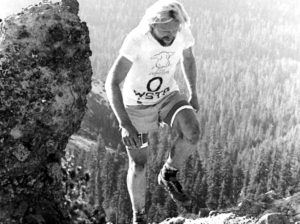

Gordy Ainsleigh

1974 was the year when Gordy Ainsleigh made his famed run on the Western States Trail in the California Sierra. Ainsleigh’s solo journey run must be mentioned, examined, and put in its proper historic context, peeling away the decades of marketing hype and myths that grew out of it.

1974 was the year when Gordy Ainsleigh made his famed run on the Western States Trail in the California Sierra. Ainsleigh’s solo journey run must be mentioned, examined, and put in its proper historic context, peeling away the decades of marketing hype and myths that grew out of it.

Early Years

Ainsleigh grew up going by the name of Harry. He was the son of Frank Leroy Ainsleigh (1926-2007) who served in the Korea and Vietnam wars, in the Air Force. Frank and Bertha Gunhild (Areson) Ainsleigh (1918-2004) married while Frank was very young. The marriage didn’t work out, and they filed for divorce one month before Gordy was born. He was then raised by his mother (a nurse) and his Norwegian-born grandmother, Bertha Fidjeland Areson (1894-1984), who was also divorced.

Frank Ainsleigh left the home, quickly remarried, and eventually settled in Florida where he raced stock cars and worked in a Sheriff’s office as maintenance supervisor over patrol cars. Bertha Ainsleigh remarried in 1952, when Gordy was five, to Walter Scheffel of Weimar, California. He was employed at a sanatorium. But Gordy’s family life continued to be in an uproar. They divorced less than a year later.

Gordy spent his childhood years in Nevada City, California (about 30 miles north of Auburn). He recalled his first long run. “One day when I was in second grade. I came out on the playground with a bag lunch that Grandma had packed for me, and I just couldn’t see anybody who would have lunch with me. I panicked. And I just felt like I couldn’t breathe. And I just dropped my lunch, and I ran home for lunch.” On another day he missed the bus for school and didn’t want to admit to his mother that he again missed it, so he just ran several miles to the school. He explained, “I came in a little late. The teacher knew where I lived. She asked, ‘Why are you late?” I said, ‘I missed the bus, so I ran to school.” She was so impressed that she didn’t punish him.

By the age of fourteen, he started to get into trouble with the law, so his mother decided it was time to move out of town, back to the country. They moved back closer to Auburn, to a small farm near the hilly rural community of Meadow Vista. In junior high school, his gym teacher treated P.E. like a military boot camp with lots of pushups. He recalled, “I’d goof off and he’d make me run. I made sure I wore a real pained expression whenever he could see me. Actually, I was having a good time.” Living on a farm, he grew up among livestock animals, and in 1964 was given an award at a country fair for a sheep.

High School, College, and the Military

But perhaps Ainsleigh’s greatest recognition in college was winning the 1967 Sierra College Pancake Tournament. “He consumed 30 pancakes, breaking his record of 24 ½ at the beginning of the competition. Ainsleigh took advantage of all the rules which allowed anything inside the mouth to be counted as consumed while pancakes still outside were disallowed.”

In 1968, Ainsleigh served in the military, and did his basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. While there, he was given an award for the highest rifle score in his company. In July 1968, he volunteered for a 21-day high altitude testing program conducted at Fort Sam Houston in Texas and at Pike’s Peak in Colorado. He took part in a series of diet and exercise tests as part of the program.

In 1969 Ainsleigh was back in California, and started to attend the University of California, Santa Barbara. He wasn’t fast enough to qualify for their cross-country team.

In 1970, he was caught up in violent anti-war and anti-apartheid unrest and rioting taking place near the UC Santa Barbara that had been going on for months. In June, police conducted raids to quell student unrest taking place during a dawn to dusk curfew. Ainsleigh was there taking part in a sit-in at a local park. He was part of a group of 200 who were ordered to disperse but did not, and then were sprayed with pepper gas. Ainsleigh claimed he had been hit by police on the skull four times and said, “I didn’t really believe one person would hit another person who wasn’t threatening him. I kept thinking that after this one, they’ll quit. I thought they wouldn’t keep beating a person on the ground, but they did.”

Endurance Riding

In 1971, at age 23, while going to UC Santa Barbara, Ainsleigh bought a horse named Rebel. One day he read a notice on a bulletin board about an endurance horse race, the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) which was held just miles from his home. He had never heard about it before but wanted to give it a try. It was a 100-mile horse race from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California.

Ainsleigh entered and rode on his eight-year-old horse, Rebel. Staggered starts were used with small groups of riders starting together. There were four key checkpoints in place that year with mandatory rest periods. Ainsleigh, disadvantaged because of his larger frame and weight, had to run many miles ahead or behind his horse to take the weight off and make faster progress. He finished in great pain at the fairground’s stadium in Auburn, with a time of 19:37. Ainsleigh said that after that 1971 ride, he began to consider running the entire Western States Trail, but it took several more years to take place.

Ainsleigh dropped out of college and worked in logging/tree-removal. He didn’t know what he wanted to do in life and felt depressed. He visited his old high school and started running long distance road races with the school’s math and music teacher. He also started to run on trails.

In 1973, Ainsleigh went to another endurance ride event, 50-miler, to attempt to run it on a $10 bet. It was the Castle Rock 50 Mile Ride, in Big Basin Redwood State Park, southeast of San Jose, California. This race was established in 1967, patterned after the Western States Trail Ride. Ainsleigh successfully ran the 50-mile course in about nine hours, finishing in the middle of the pack of riders who had two mandatory one-hour stops. That year Ainsleigh also finished a marathon in a very impressive time of 2:57:07, weighing more than 200 pounds.

On July 14, 1973, Ainsleigh rode the Western States Trail Ride for the third year but only made it to Robinson Flat (mile 30), which took him seven hours. His horse, “Old Rattle Nose” was lame and couldn’t continue, so he dropped out of the race. He never replaced that horse and thus didn’t have one for the next year’s race.

It wasn’t until 2020 that Ainsleigh admitted in public that the soldiers were indeed the first to cover the course on foot during the Tevis Cup. However, he disparaged the attempt. “When Wendell announced at the pre-ride meeting on Friday in 1972 that a crack marching team from Fr Riley KS had started out that morning, and were planning to finish before 5 on Sunday morning, I said to myself, ‘What? Anyone can do that!’ . . . The commanding officer should have been court-martialed for sending out untrained soldiers into such a stupid task.”

Western States 100 established, along with exaggerated claims

In later years, others would try to run the course too, but it wasn’t until 1977 that Wendell Robie, President of the Western States Trail Foundation, finally decided to organize the Western States Endurance Run. Ainsleigh was not the founder of the Western States Endurance Run, Wendell Robie was. Ainsleigh did work hard for the 1977 race that came under the direction of Mo Livermore. But as planning occurred for the 1978 race, Ainsleigh was very disappointed that he was not appointed as an officer on the first board of governors for the race. He was on the board but was relegated to a marketing role, to be brought out once a year to tell his tale and promote the race.

For 1977 and 1978, the marketing effort for Western States came together. The board strategically decided to “prop up” Ainsleigh’s story of his run and make him into the icon of the emerging race.

Ainsleigh did love the attention and he was skillful and dynamic in his role. The board also purposely decided to bury the 1972 story of the soldiers. Ainsleigh was proclaimed in marketing material and news stories as the first to cover the 100-mile course on foot.

The Western State origin story continued to be enhanced by Ainsleigh and the 1978 race organizers, who made some over-reaching historic claims. These people were primarily horse endurance riders, and were just becoming ultrarunners. They were focused on California, knew nothing about the history of ultrarunning and what was going on with 100-milers across the world. They did not know that nearly 1,000 athletes had already covered 100 miles on foot in less than 24 hours on tracks, roads, and trails before Ainsleigh’s run. Historic accuracy was not their focus, marketing was.

The 1978 Western States Board of Governors thought their race was the first 100-miler and started to make that inaccurate claim. The focus for Robie and these organizers was to make Auburn California “the endurance capital of the world.” Despite their over-reaching claims, their efforts were amazing and would bring Western States 100 into the world spotlight. Dozens of 100-milers would pattern their races after Western States.

The 100-mile ultrarunning history claims would continue to grow through the years. Ainsleigh, who was a mid-pack runner, was proclaimed by some as being “the godfather of the sport,” ignoring the true modern-era contributions by Ted Corbitt in New York. Ainsleigh was also called, “the man who invented trail ultrarunning” a claim that Ainsleigh embraced on his personal website and on podcasts for many years. Trail ultrarunning, including races had existed for decades before Ainsleigh was born. Hopefully, the preceding 12 parts of this 100-mile history have preserved the true rich history of the 100-mile sport that early Western States marketers most likely did not know about. Despite the claims, Ainsleigh went on to be an important ambassador for the sport ultrarunning. To his credit, he was the man who put the greatest spotlight on trail ultrarunning as it was evolving in the 1980s.

1974 Western States Backpackers

While Western States founder Wendell Robie wasn’t mentioned, he likely was involved because he was president of the Western States Trail Foundation. This further built on the “Western States on foot” idea that originated with the Fort Riley soldiers two years earlier. Ruth Clark, a volunteer organizer for the event said, “the Trek will provide a unique opportunity for those representing Placer County to combine recreation and community service.” Between 50-75 participants were encouraged to sign up and “would be sponsored by local business and individuals raising funds on a per-mile basis.” Participants needed to have their own backpacking gear but would be provided food along the way.

Backpackers young and old, male and female signed up for the trek. A week before Ainsleigh’s run, Eleanor Macsalka, an elementary teacher from Ainsleigh’s hometown of Meadow Vista was highlighted in the Auburn newspaper, seeking pledges for her planned 100-mile trek. There is just no way that Ainsleigh can be given exclusive credit for the idea of covering the Western States Trail on foot.

Fifty-six backpackers started on August 10, 1974 from Squaw Valley and 53 completed the eight-day march. “Blisters, sore feet and tired muscles were numerous among the finisher who ranged in ages from 13-71. The oldest participant, Orvis Agee, 71 of Woodland, reportedly out-hiked many of his younger fellow backpackers.”

A big luncheon for the group was held on August 18th at the Auburn Fairgrounds. About $10,000 of pledges were made for the Lung Association. The backpackers said they had a great time and planned to have reunions to commemorate their historic hike.

The trek went on to be held as an annual event for the next eleven years, although the route changed somewhat each year. During the later years, it went between Lake Tahoe and Yosemite.

For more legends, myths and folklore about Western States 100, see Episode 28.

Canadian 1974 100-milers

Camellia 100

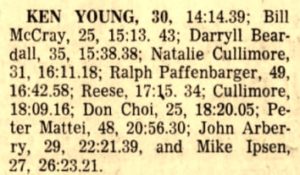

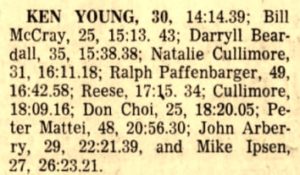

The 1975 edition of the Camellia 100, held on March 7th went better with 14 starters. It was held on a 7/8th mile loop north of the Cal Expo main gates in Sacramento. John Hill of Sacramento was the race director. Heavy rain fell during the first five hours but two finished, Bill McCray, 25, of Norton Air Force Base with 15:13:43, and Don Choi (1948-), 26, a mailman from San Francisco, finished his first 100-miler with 18:20:05. In the five year history for this 100-miler, there were a total of 11 finishers.

1974 Durban 100

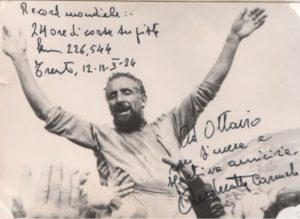

Carmelo Andreatta

But his fame came when he became a pioneer Italian ultrarunner in 1974-1977. On October 12, 1974, at the age of 51, he broke the Italian 24-hour record, reaching 140.7 miles on a track in Trento. He had trained barefoot, even in the snow, and often during the night.

The 1975 Queensborough 100

Barner was famous for his “back-to-back” runs. For example, in 1973 he finished a 50 km race in Vermont and the very next day finished 3rd at the inaugural Harrisburg Marathon. (For more about Barner, see episode 51.)

By 1975, Barner had run more than 30,000 miles and had ran 5,400 miles the past year. He had been receiving some strange criticism because he trained so much. It rankled Barner, so he used a new approach to combat the criticism. He said, “I wanted to prove they were wrong.” For the first eight months of 1975 he averaged only seven miles of light running per day. That was his training for his first 100-miler.

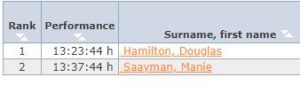

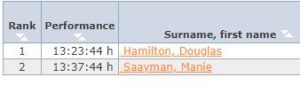

The venue for the 1975 Queensborough 100-miler was on the college quarter-mile track. There were only seven starters and all but Barner dropped out along the way. He reached 50 miles in 6:32, but without any competition he faded during the second half of the race. He won with a time of 13:40:59 for a lifetime best. It was just seven minutes slower than Ted Corbitt’s 13:33 track 100 mile American record, set in 1969 in England (see episode 63).

Barner tried to break Corbitt’s record the next year at the same event and was leading at mile 67 when he injured his hip. The temperatures were in the 90s, so he decided to drop out. It appears that there were no finishers that year.

100-mile Solo Attempt

Garner had to eat his words, when on November 29, 1975 he started an attempt to run 100 miles. He was hesitant and said, “This is an attempt. I’m not saying I’m gonna make it. But with the condition I’m in, I just feel full of confidence. My mental attitude is right and my determination has never been better.” He had learned from mistakes on his last run when he drank only water. He learned all about replacing electrolytes. He naively had hopes to reach 100 miles in 19.5 hours.

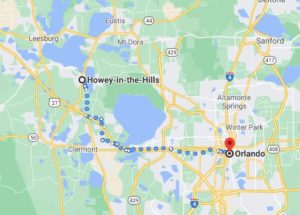

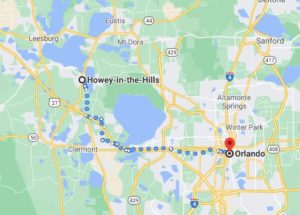

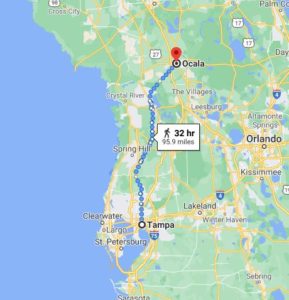

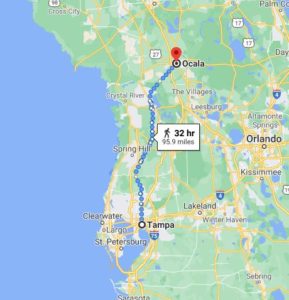

The planned route was from Starke to Leesburg, Florida. The Cancer Society provided a crew vehicle and a doctor to go along. His journey began in the afternoon, on May 29, 1976. He ran the first 12 miles in bad heat, not stopping for any fluids. But after 24 miles he started to have stomach pains and then refused to drink any more electrolyte fluids. His crew knew “that was a bad sign, the beginning of the end.” His pace slowed to a snail’s pace and he again quit, this time after nine hours, reaching only 30 miles. The heel in his right tennis shoe had also worn ragged. $700 were raised. His sponsors were grateful, but very alarmed that Garner was doing harm to himself. That was the last of his 100-mile attempts. He died about 25 years later.

Women’s 100-mile Relay

On June 6, 1975, at Stafford, New Jersey, an all-women’s relay ran 100 miles in 13:46:02. Ninety-three were students from Southern Regional High School and seven others were teachers at the school. They each ran one mile, covering a total of 400 laps around the school’s cinder track. The track coach, Brian Cahill said, “As far as we know, no all-female team had ever done this before.” The fastest mile was run in 6:15 by a track star, 17-year-old, Fay Wiseman, and the slowest was 12:15 by a teacher. The fastest teacher was Diane Depreter with 7:53. A boy’s team of five ran concurrently and finished their 100 miles about an hour ahead of the women.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Auburn Journal (California), May 8, 1947, Sep 18, 1952, Sep 17, Dec 15, 1964, Jul 31, Aug 23, 1974

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Nov 20, 1965, Mar 10, 22, 1975

- The Placer Herald (Rocklin, California), Nov 23, 1966, Jun 20, 1989

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), May 19, 1967, Jul 15, Aug 6, 1974

- The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), Apr 26, Jul 26, 1968

- Arizona Republic, (Phoenix, Arizona), Jun 12, 1970

- The Times (Nanaimo, Canada), May 25, Oct 1, 1974

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Apr 23, 1973, Oct 1, 1974

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), May 27, 1974

- The Leader-Post (Regina, Canada), May 28, 1974

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Dec 5, 1975

- Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida), May 10, 1075

- Ashbury Park Press (New Jersey), Jun 7, 1975

- The Orlando Sentinel (Florida), May 29, Aug 10, Nov 25, Dec 2, 1975, May 11, 27, Jun 4, 1976

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Jan 12, 1997, Dec 24, 2015

- gordonainsleigh.com

- Gordon Ainsleigh, the first trail ultra

- A Horse Race Without A Horse: How Modern Trail Ultramarathoning Was Invented

- NorCal Running Review No 46.

- “Carmelo Andreatta, the man of many goals”