Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:27 — 28.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Episode 75 introduced the Fort Meade 100 held in Maryland from 1978-1989. Lost in the Fort Meade history of the late 1970s was the fact that it also attracted Centurion racewalkers who attempted to walk 100 miles in less than 24-hours. It was reported, “Some participants were walkers engaged in an odd-looking sport of walking heel-to-toe as fast as possible. It’s a small sport, there’s a lot of camaraderie in it, with only about 600 people participating nationwide.”

Episode 75 introduced the Fort Meade 100 held in Maryland from 1978-1989. Lost in the Fort Meade history of the late 1970s was the fact that it also attracted Centurion racewalkers who attempted to walk 100 miles in less than 24-hours. It was reported, “Some participants were walkers engaged in an odd-looking sport of walking heel-to-toe as fast as possible. It’s a small sport, there’s a lot of camaraderie in it, with only about 600 people participating nationwide.”

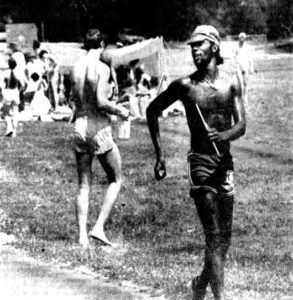

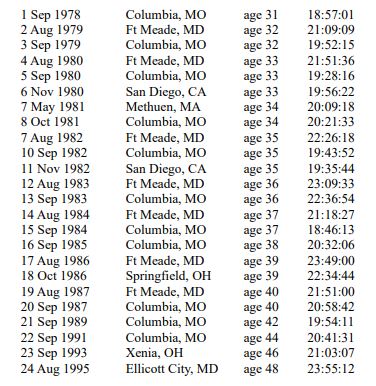

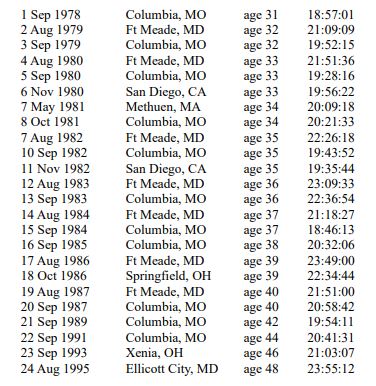

Alan Price, an African American racewalker, was a fixture at Fort Meade 100 each year. He was an incredible athlete who became perhaps the greatest American ultra-distance racewalker ever. Price was truly an ultrarunning legend.

Also covered in this episode is a division of the ultrarunning sport that most Americans have never heard about before. It is The Long Distance Walkers Association (LDWA) in England that started holding 100-mile walking events during the 1970s that attracted the general public and some 100-mile runners. The events set the stage for many of the modern 100-mile trail events.

Alan Price – 100-mile walker

It took Price some time to get the walking technique down. He said, “There can be a thin line between walking and running. It all depends on how the judges view it. When I first started out, I was guilty of things like not having both feet on the ground at all times. That made me more careful than anything else. It’s no fun to go out for five or six miles and then have someone disqualify you.”

As a black American, Price was a pioneer in the sport. He became a member of the Potomac Valley Seniors track club and said he felt funny practicing his walking in the daylight in Washington D.C., so he would train in the darkness of night at the track at Bennicker Junior High School. He said, “People who don’t do this, think it’s easy. That’s because they haven’t tried it yet.”

Just as today, the ultra-walking sport back in the late 1970s wasn’t well understood by the public. Price would be the object of taunts and laughter. “People saw the switching of the behind and arms flailing, and they seemed to get a big kick out of it. But after seeing for a while, they begin to realize that there must be some difficulty in it. People who saw me train in Malcolm X Park over the years respected what I was doing.”

Price first walked for personal satisfaction. He said, “It was something that I felt natural doing.” Then in 1976, he went to a meet at Niagara Falls, New York, where the top racewalkers in America were trying out for the Olympics. The top three finishers qualified, and he was only one minute behind. He said, “I was surprised, and it was at that point that I knew I could hang with the big boys.”

Episode 63 introduced “Centurions,” a brotherhood of walkers who had reached 100 miles in a judged racewalking event. Larry O’Neil (1907-1981), a lumberjack from Kalispell, Montana was America’s 100-mile walking pioneer who dominated events during the early days, setting in 1967 the American out-door record of 19:24:34. The world record was held by Huw Neilson (1924-) of Great Britain with a time of 17:18:50, set in 1960 at Walton-on-Thames, England. Neilson continued on, reaching a walking world record of 131 miles in 24 hours. His world records are still held to the present-day.

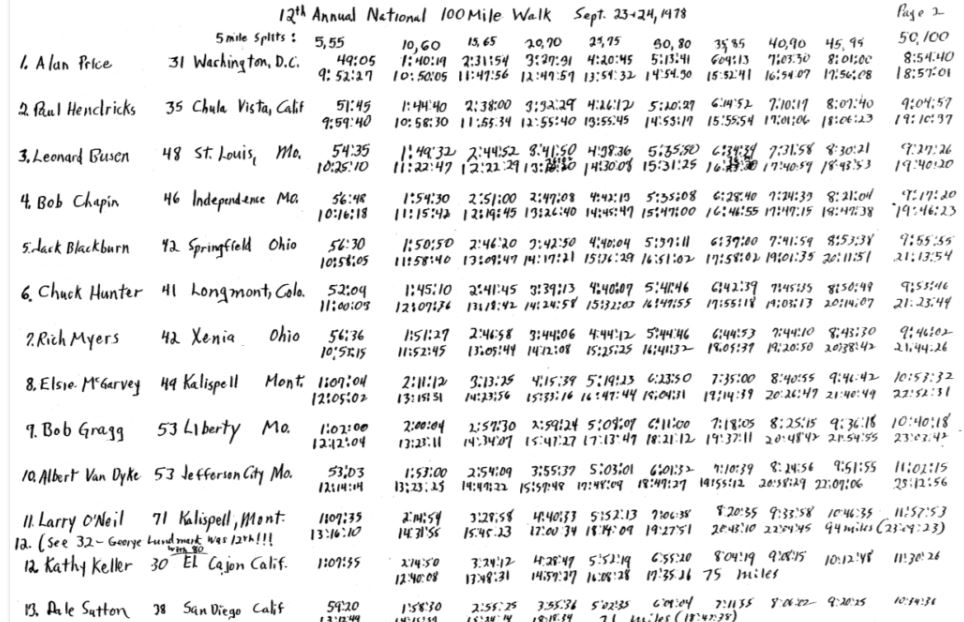

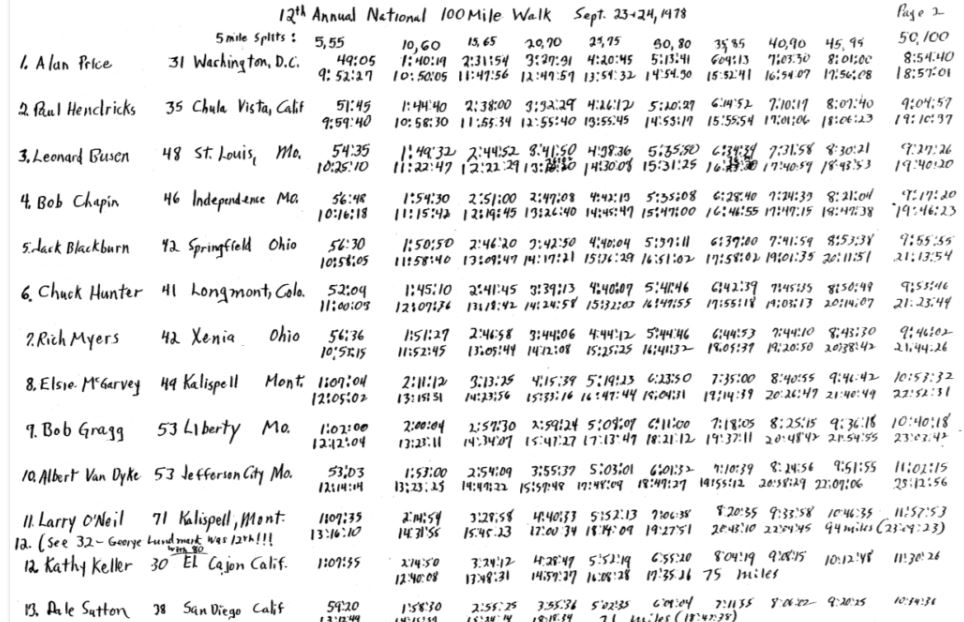

1978 Columbia 100

The weather for the historic 1978 race was perfect. Thirty-seven walkers competed including the defending champion, Paul Hendricks (1943-) a high school teacher from Chula Vista, California. Hendricks was confident that he could defend his title with his experience and technique. He said, “If you racewalk in a competition against top class racewalkers, you will hurt more than in a running competition.”

Price remembered, “I kept telling myself that I wanted that record and that’s what kept me going. I’ll never forget the feeling I had when that warm sun came up the following morning. It was like new life was being injected into my body.”

Price recovered and put on a chase, taking the lead at mile 82. “Hendricks succumbed to the effects of his hard effort to take the lead. This time he had no response and Price continued to pull away over the last 15 miles to take a very hard-fought and well-earned victory.” He crossed the finish line first and broke O’Neil’s American record with a mind-blowing walking time of 18:57:01. Henricks finished 13 minutes later. Eight other walkers reached 100 miles in under 24 hours. The veteran walker, O’Neil, age 71, reached 94 miles.

Price becomes the greatest American 100-mile ultra-walker

By 1980, Price was the 10th fastest racewalker for the shorter 50 km distance in the United States. He credited his training regimen for his endurance and stamina. “In the winter, it’s too cold to walk, so I train by running distances up to 100 miles weekly. On the other hand, it’s too hot to run in the summer so I walk the same distance. That’s how I get balance out of my training.”

In 1982, Price was invited to race against multi-day legend Don Choi (see episode 74) in an exhibition 100-mile walking match. “The race promoters figured walking a 100-miler would be a piece of cake for Choi. Price blew him away in 19:35:44.” Price said, “Well, he finished it, but he was hurting pretty bad. I asked him which he thought was harder, a six-day run or a hundred-mile walk. He replied, ‘No doubt about it, a hundred-miler!’” Price liked having one of the best runners in the sport invading his turf and come away shaking his head.

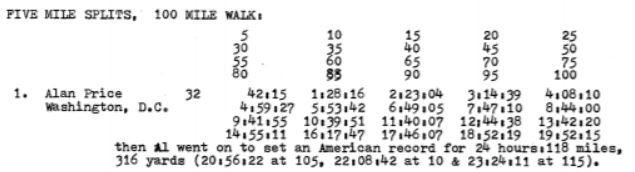

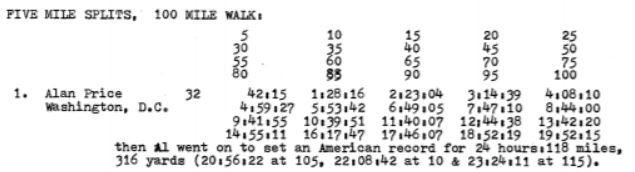

1984 American 100-mile Walking Record

In 1984, at the age of 37, Price recaptured the American 100-mile outdoor record with a time of 18:46:13 at the Columbia 100. (Larry Young had set a 100-mile indoor mark of 18:07:12 in 1971 when the Hickman track was flooded and the Columbia race was moved to Brewer Fieldhouse on a 220 yard dirt track.).

Twenty-three walkers started the 1984 race. That year it was the TAC National 100-mile walking championship. For the first time that year “pacers” were banned from the track. The cool weather was an important contributor to Price’s success, with a high in the 60s and low of 32. The ultra-racewalking community agreed that Price was the best 100-miler in this country by a wide margin.”

Fort Meade 100

He had at least seven Fort Meade 100 finishes, only second to Ray Krolewicz, who commented, “Alan Price would come out every year and racewalk like a beast. He had beautiful form and never stopped. When I developed my survival shuffle, it basically was modeled after Alan. I would get behind him walking and shuffle. I knew if I could do that pace, it would carry me. Someone once told me my shuffle was a valid racewalk.”

Dan Brannen wrote, “I never fully appreciated the sheer natural beauty of flawless racewalking technique until I had the pleasure to witness Alan Price in action, side-by-side, at the 24-hour event at Fort Meade. The smooth perfection of his form was astounding, and mesmerizing. It seemed to defy the natural limitations of human two-legged fluidity of forward motion.”

Price Continues to Walk

In 1985, Price walked from Los Angeles, California to El Paso, Texas as part of a Mothers Against Drunk Driving March Across America. That year he won his eighth Columbia 100 in a row

Price’s Walking Career

He was remembered as a fierce competitor with a contagious smile. One fellow walker wrote, “He clearly was by far the best long distance walker ever. I can still see him sleep walking and then waking up and accelerating by me, leaving me in the cinders! But even more than that he was a warm, wonderful spirit. He touched many people.”

The Long Distance Walkers Association (LDWA) 100s

The 1978 Cleveland Hundred

One walker, Peter Parker wrote a letter of thanks to the LDWA staff that included, “The pains have left my feet and I’m writing to tell you how very much I enjoyed this year’s Cleveland Hundred. As I climbed up Baysdale, I was aware of a feeling of supreme happiness. I cannot ever recall such blessedness as in the superb dawn in that beautiful place. For me, C100 1978 will have the fondest memories in my life and I want to thank you and your team for making them possible.”

The 1979 Dartmoor Hundred

“After a slight delay waiting for the Deputy Lord Mayor, the walkers were loaded onto the double deck buses for transportation to the start at Cadover Bridge several miles away. The steady drizzle and mist looked at little ominous and just about everyone donned full rain gear. Once out of the busses the gaudily clothed crowd listened to a few words of advice from the starter and then at 12:15 p.m. they set off on a giant anti-clockwise circuit of the Moor.”

Things didn’t start out smoothly as the crowd went a bit off course on the first hill and then screeched to a stop at a waterfilled trench of unknown depth. “Where the bridge mentioned in the route notes was nobody knew. After various sorties to left and right, long jumping skills were tested with the result that most people prematurely wetted either one foot or both or in some cases a more extensive area.”

Gradually the walkers were strung out over many miles. After only ten miles, some quit. Once the evening dusk approached, many called it a day. The runners started about six hours after the walkers and caught up to the pack during the night. Navigation problems were many. “At one stage about twenty walkers were struggling through bog and tussock grass searching in vain for the path alongside the River Plym. Eventually some decided to bed down until daylight. Others thrashed about in aimless circles and a few went on to find the ford to Cadover Bridge.”

Sandra Brown from the UK, who has finished more than 200 100-milers and dozens of LDWA walks commented,

The LDWA Hundred has continued annually to present-day with up to 500 participants each year and an average finish rate of 70%. Only two years were cancelled, 2001, because of foot and mouth disease in the countryside, and in 2020 because of COVID-19.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- Alan Price – Centurion Legend

- The Washington Post, May 15, 1980, “Alan Price: One Fine Walker”

- Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1989

- Centurion Footnotes, Jan 2015

- United States Centurion Walkers

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), Aug 6, 1979

- The Billings Gazette (Montana), Sep 16, 1988

- The Long Distance Walkers Association

- LDWA 100s Archives – Route, Results and Certificates

- Interview with Ray Krolewicz, Mar 24, 2021

- Chula Vista Star-News (California), Apr 20, 1978