Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:33 — 32.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

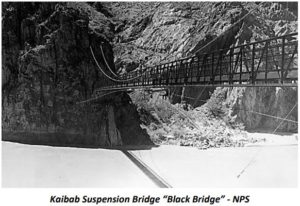

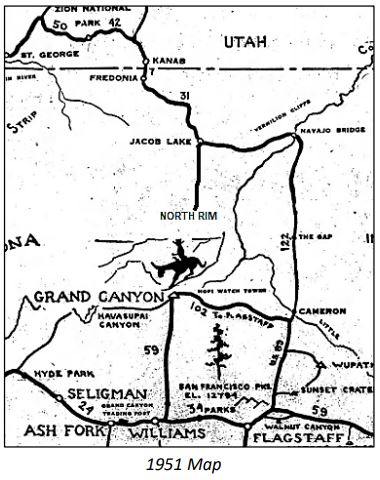

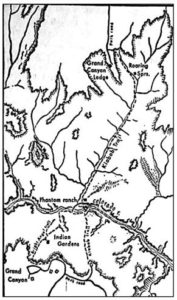

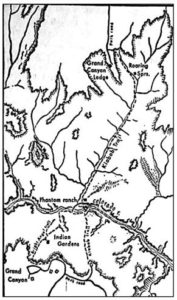

This part will cover additional stories found through deeper research, adding to the history shared in Part 2 of this Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History. These stories can also be found in the new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. By 1927, Phantom Ranch was well-established at the bottom of the Canyon. The new South Kaibab trail was complete, and the Black Bridge was nearing completion. On the North side, the North Kaibab trail up Roaring Springs Canyon was also nearing completion, which would make the rim-to-rim hiking experience much easier instead of using the “Old Bright Angel Trail” that went steeply up to the North Rim. During the early 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) had a camp across from Phantom Ranch and worked on many significant projects, including the River Trail along the Colorado River. Their story can also be found in Part 2.

This part will cover additional stories found through deeper research, adding to the history shared in Part 2 of this Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim History. These stories can also be found in the new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. By 1927, Phantom Ranch was well-established at the bottom of the Canyon. The new South Kaibab trail was complete, and the Black Bridge was nearing completion. On the North side, the North Kaibab trail up Roaring Springs Canyon was also nearing completion, which would make the rim-to-rim hiking experience much easier instead of using the “Old Bright Angel Trail” that went steeply up to the North Rim. During the early 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) had a camp across from Phantom Ranch and worked on many significant projects, including the River Trail along the Colorado River. Their story can also be found in Part 2.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. Read more than a century of the history of crossing the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim. 290 pages, 400+ photos. Paperback, hardcover, Kindle, and Audible. |

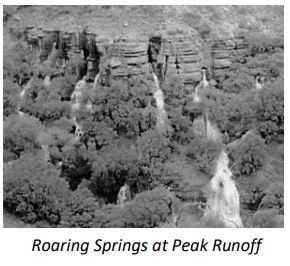

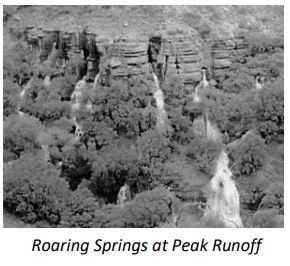

Power and Pump Stations at Roaring Springs

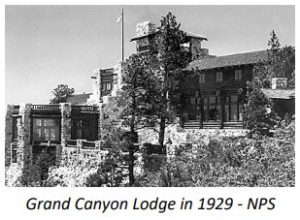

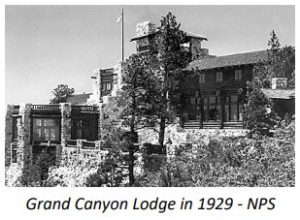

Grand Canyon Lodge at the North Rim

Grand Canyon Lodge Burns Down

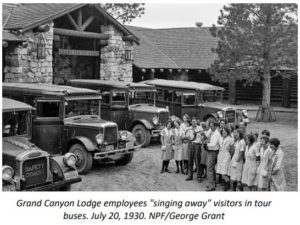

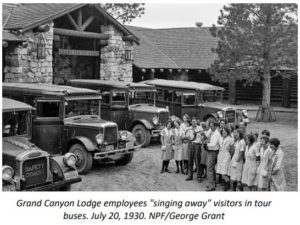

On September 1, 1932, at about 4 a.m. a kitchen fire broke out in the Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim. As John Richards, the chief chef, was preparing breakfast for the employees, sparks flew, and a blaze started. He quickly sounded the alarm. Twenty girls from Provo, Utah, employed as waitresses, fled their dormitory on the second floor. “The guests in the adjoining cabins were aroused and many volunteered in preventing the spread of the flames to the more than 100 cabins situated around the central lodge. The flames spread so rapidly that it was impossible to save the personal effects of the employees and the rich furnishings in the building.” Within an hour and a half after the fire was discovered, the Lodge was a raging inferno. Some wet blankets draped over nearby cabins prevented the fire from spreading.

The blaze was visible for 13 miles from the South Rim. Superintendent Miner Tillotson, thinking it was a forest fire, flew over at daylight discovered the devastating damage. “Occupants of two burned deluxe cabins lost personal belongings in their haste to reach safety when the flames spread to their quarters.”

The fire left the famed Lodge “a smoldering mass of charred logs and cracked masonry. The loss, including a curio shop, cafeteria, amusement hall, park offices, and a post office, was estimated to be valued at $500,000. Among the fifty guests at the time were Latter-day Saint Church apostle and future president, George Albert Smith (1870-1951), and his daughter. For four years, the ruins stood undisturbed.

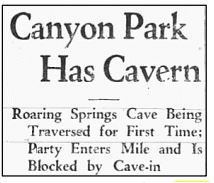

Roaring Springs Cave Explored

“At one point, the explorers found one side cavern of some considerable length. No very large rooms were discovered, though the cave was easily negotiable throughout the entire length examined. With proper equipment and guidance, park visitors to the Roaring Springs region could easily be afforded an opportunity to experience the thrill of subterranean exploration in this cave.” Today, the cave entrance is gated and locked.

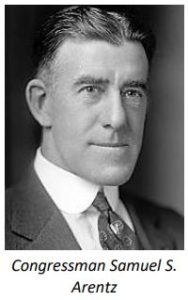

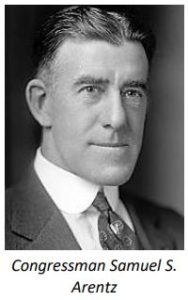

Fire on Bright Angel Trail

“Just below Indian Garden, the party came suddenly upon a fire caused, presumably, by smokers in a trail party which had passed a few minutes previously. Congressman Arentz happened to be about 100 yards in the lead and found the fire burning fiercely and spreading rapidly in the dry brush. He immediately started fighting it with his bare hands and succeeded in holding the flames in check until the other two hastily arrived to assist in beating out the fire.”

Congressman Arentz came away with singed eyebrows and torn and burned clothing. Congressman Appleby said, “It is the duty of every American citizen to become personally familiar with the National Parks.” He believed that the Grand Canyon “was second to none for its beauty, grandeur, and diversified character of its scenery.”

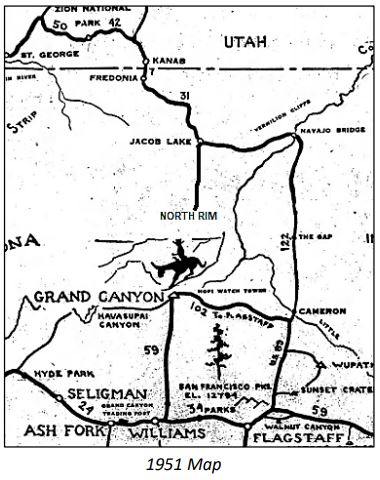

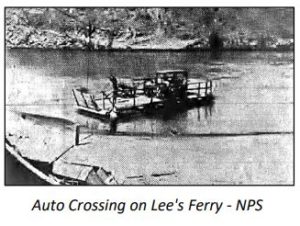

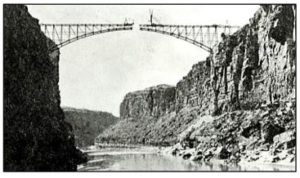

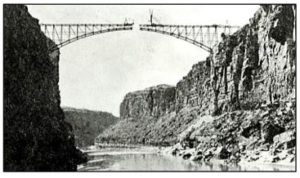

Navajo Bridge Over the Colorado in Marble Canyon

The original bridge still exists today as a pedestrian bridge. It was replaced in 1995 by a new bridge that was built 150 feet downstream that could handle heavier and wider vehicles.

Bright Angel Trail improvements

Cycling Rim to Rim

In late June, he rode to the North Rim from Kanab, Utah, and then got permission from the Park Service to ride his bike across the Canyon. “He made the trip on his bicycle from the North Rim to the South Rim over the famous Kaibab Trail, covering this distance in a little more than eight hours. According to the rangers at the Canyon, it takes a full day to make the same trip by mule back and 12-14 hours on foot.”

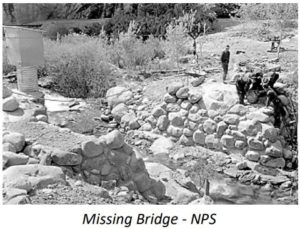

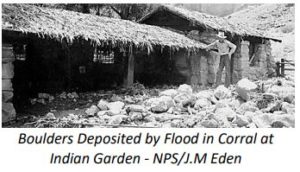

1936 Flood

Louis “Leo” Lester Purvis (1910-2006), age 26, recalled, “Since the cloud cover remained throughout the night, it was necessary to burn the flashlights at all times. Even though the trail was almost obliterated, there was enough evidence left to follow it. Boulders littered the trail and signs of landslides were on every hand. Every step was made with extreme caution for fear of starting another rockslide.” By the time they reached Bright Angel Creek, the water had subsided, running normally. “The high water had made a boulder field out of the trail area.”

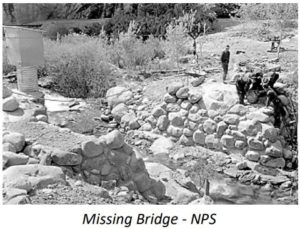

The flood destroyed the water pipeline going up to the North Rim. Damages were estimated at $50,000. Temporary water facilities were provided for the North Rim Lodge and camp. The North Kaibab Trail was closed. CCC enrollees went to work repairing the damage.

Snowy Rim to River and Back Attempt

They successfully made it down to the river. On their return to Indian Garden, they were advised to stop there until the storm passed, but they refused to heed the warning. As they were climbing back up, they were hit with one of the worst blizzards locals had remembered, which dumped 2-3 feet of snow on the South Rim. “Pultorak became exhausted, and his companion endeavored to carry him, but realizing the impossibility of the undertaking suggested that they retrace their steps to Indian Garden and await more favorable weather conditions. Pultorak didn’t approve of the idea and when Des Jardin decided he would return to Indian Garden, Pultorak, somewhat recovered from his exhaustion, decided he would continue to the top.”

The next day, Wilber Wright and his wife descended on mules. They found Pultorak dead in a snow drift with his legs sticking out. Des Jardins was found in the rafters of the rest house, in critical condition. He was brought back up on the back of a mule and was so badly affected that he could not talk. His feet were terribly frostbitten but were saved, although he lost one toe.

Recognized Rim to Rim FKT

Pigeons Race Out of Grand Canyon

Many of the speedy birds were successful. The winner was a bird named Henry. The bird owned by Sam Crowe (1898-1955) of Topeka, Kansas, flew to Prescott in 3:23. It broke the Grand Canyon FKT for birds by 23 minutes.

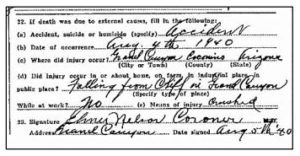

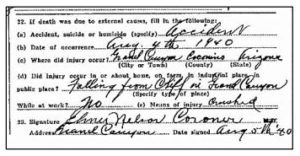

Death on the Trail

Rim to Rim in the 1940s

During the 1940s, many went to defend the country fighting in World War II. There were few daring rim-to-rim hikers during that time. Nearly all the journeys across the Canyon involved mule rides. It was emphasized, “Mulebacking is recommended for all but top-conditioned hikers.” Most of those people who ventured up Bright Angel Creek were seeking fish.

A few hikers made the rim-to-rim trek in multiple days and newspapers would make a big deal out of it. In 1941, R. L. Fry and his eldest son Bobby hiked rim-to-rim, starting at the North Rim, and indulged in a little fishing on the way in Bright Angel Creek. They took a day and a half.

Tourists on the rim would “gawk” at the unusual hikers who came out of the canyon by foot. One hiker wrote in 1941, “Arrived at the top to amusement and amazement of visitors, who had been following our progress with interest and who roamed around us as we rested, snapping pictures as if we were a newly discovered Indian tribe or something.” A college hiking club at Flagstaff, Arizona, made annual group hikes into the canyon for many years.

In 1943, Frederick F. Hoerger, a poet from Greenwich Village, New York City, went on an adventure. “He took the bus to Jacob Lake and, carrying a 25-pound pack, hoofed it over the Kaibab Trail across the big gorge. He spent two nights out in the open. Not our idea of fun, but it’s quite an accomplishment.”

Visit to Phantom Ranch

In 1942, extensive repairs were made to the buildings and sewer lines at the ranch. All the cabins had air-conditioners installed to pamper the guest during the hot summer months.

Grand Canyon Visitors Increase

A small peach orchard at Phantom Ranch was now over 20 years old. Hikers passing through would, at times, snatch one or two of the delicious fruit. In 1947, a tourist from Ohio felt guilty about their thievery and mailed in five dimes to the Grand Canyon ranger station. A letter was enclosed that read, “I am enclosing 50 cents in coins for peaches I ate from the orchard on the floor of the canyon several years ago. I wish to express my regrets, but at that time I didn’t consider it wrong.”

Easter weekend started to be a traditional popular weekend to hike down into the Grand Canyon. In 1948, a large group of nearly 100 members of the Sierra Club made their way down to Phantom Ranch.

Drag-outs and Guides

During the 1940s, three women hiked down wearing “tennis shoes,” and developed terrible blisters. They planned to stay overnight at Phantom Ranch and wanted a mule ride back up. Clevenger said, “Tell you what, I’ll feed them mules plenty of soft hay tonight so’s they’ll be nice and soft to ride tomorrow. Course we got nothin’ left but blind mules, but them mules hear real good.” The next day, the women were worried that the mules would go off the trail. Clevenger yelled, “Mules and horses don’t never commit suicide. We ain’t goin’ off into the river if you shove us with a bulldozer.” He asked the ladies, “Any of you girls rich widows?” but remember, “Nah, I saw your ugly husbands.” The tennis-shoed husbands had elected to hike back up. In 1969, Clevenger died in an accident while working in the Four Corners area.

Weather Impacts

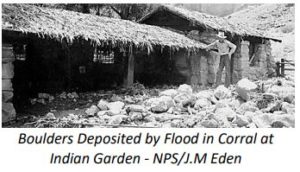

A fierce thunderstorm on September 30, 1946, dumped 1.5 inches of rain within a short period, on the South Rim. Water was running in a river at Indian Garden. The Bright Angel Trail was seriously damaged and closed for a week to make repairs.

1948 was a low snow year for the North Rim. Rangers were able to easily conduct a rim-to-rim journey in late January on mules, and the North Kaibab Trail was free of snow. Peach trees at Phantom Ranch were blossoming in March. 1949 was a record year for snow at the Grand Canyon. By February, 78 inches of snow had fallen at the South Rim. Eight inches of snow had been seen at Cottonwood Campground on Bright Angel Creek, “something entirely unheard of.” A trail crew trying to keep the trails open was trapped down in the Canyon for several days.

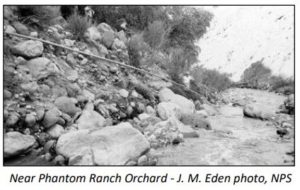

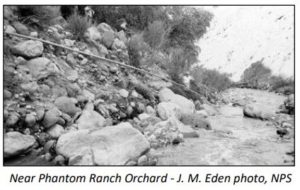

1948 Flood

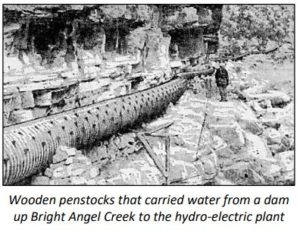

On August 5, 1948, heavy rains caused flooding down Roaring Springs Canyon and Bright Angel Creek. It knocked out the power and water plant down at Roaring Springs, which caused the North Rim lodge and cafeteria to be shut down. “Severe damage to Kaibab trail was reported. On the South Rim, Bright Angel Trail was washed out, but the damage was not serious.” It would take a week to repair that trail.

1949

In August 1949, hikers were issued cautions after a large rock fall narrowly missed a mule party of eight going up Bright Angel Trail, throwing two people off their mules, uninjured, but badly frightened.

On July 28, 1949, two young men, employed by the Utah Parks Co. connected with history and went down the old Bright Angel Trail on the North Rim, which had not been used for more than 20 years. They made it down about four miles, went off trail, and then Irvin Delbert Bird Jr. (1930-2009), age 19, of Tooele, Utah fell and was severely stabbed in the leg by a sharp spine of an agave plant. His companion, Donald Price Van Steeter (1929-2004), of Salt Lake City, went down to the Roaring Springs power plant, and used the telephone to call for help. A ranger party with a mule rescued the embarrassed young man.

In 1949, Harry E. Brown, a fire control employee for the Park, ran what is believed to be the first double-crossing in less than 24 hours. Brown was a World War II veteran who served in China. In 1950 he went on to be employed by the Forest Service near Frazer, Colorado and then returned to duty as an officer in the Marine Corps in 1953, where he volunteered for cold weather combat training in the Sierra Mountains of California.

Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim Series

- 46: Part 1 (1890-1928)

- 47: Part 2 (1928-1964)

- 48: Part 3 (1964-1972)

- 49: Part 4: Aiken Family

- 50: Part 5: The Races

- 135: Part 6: Early Guides

- 136: Part 7: Prof Cureton

- 137: Part 8: Kolb Brothers

- 138: Part 9: Phantom Ranch

- 139: Part 10: More on 1927-1949

- 141: Part 11: More on 1950-1964

Sources:

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), May 6, 27, 1928, Sep 9, 1928, May 13, 1930, Aug 1, 1932, Jul 20, Oct 25, 1933, Mar 11, 1934, Jul 22, 1935, Aug 9, 1936, Jun 16, 1941, Mar 21, 1846, Aug 6, 1948

- Los Angeles Times (California), Feb 9, 1929, Aug 7, 1938

- Williams News (Arizona), Dec 2, 1927, Jul 13, 1928, Feb 16, 1939, Sep 4, 1941, Feb 26, 1942, Oct 21, 1948

- The Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Sep 16, Oct 7, 1927

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Sep 16, 1928, Sept 2, 1932, Mar 6, 1934, Feb 24, 26 1937

- Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), Sep 15, 1928, Sep 1, 1934, Jun 28, 1949

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Aug 6, 1948

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), May 8, 1928, Jun 16, 1929, Feb 23, 1937, Mar 31, 1940, Mar 23, 1947, Aug 7, 1948

- Arizona Daily Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), Oct 8, 14, 1946, Jan 19, Aug 6, 9, 1848, Oct 13, 1948, Jan 17, 26, 1949

- The Richfield Reaper (Utah), Jun 13, 1929

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Nov 27, 1927, Apr 5, Jul 8, 1928

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Jan 9, 1927

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Jul 2, 1922, Jan 23, 1927

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (California), Feb 26, 1927

- Redwood City Tribune (California), Apr 18, 1927

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Hawaii), Feb 20, 1928

- The San Bernardino County (California), Sun, Mar 4, 1928

- Omaha World-Herald (Nebraska), May 6, 1928

- Brooklyn Times Union (New York), May 9, 1928

- The Salt Lake Mining Review (Utah), Jan 15, 1929

- The Leader-Post (Regina, Canada), Jul 20, 1929

- The Needles Nugget (California), Sep 6, 1929

- Parowan Times (Utah), Sep 11, 1929

- The Perry County Democrat (Bloomfield, Pennsylvania), Nov 6, 1929

- Greeley Daily Tribune (Colorado), Mar 14, 1930

- Santa Cruz Evening News (California), Jun 26, 1930

- Lithgow Mercury (New South Wales), Mar 21, 1930

- Ames Daily Tribune (Iowa), Aug 15, 1933

- The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), June 6, 1933

- The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Jun 16, 1934

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jun 27, 1934

- The Santa Fe New Mexican (New Mexico), Feb 26, 1935

- Carlsbad Current-Argus (Carlsbad, New Mexico), Mar 1, 1935

- The San Bernardino County Sun (California), Nov 16, 1935

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), Aug 21, 1936

- The Hanford Sentinel (California), Feb 22, 1937

- The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Feb 22, 1937

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Aug 7, 1938

- Battle Creek Enquirer (Michigan), Feb 10, 1939

- The Benkelman Post (Nebraska), Aug 23, 1940

- The Miami News (Florida), Jan 7, 1940