Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:19 — 36.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

The 1977 Western States 100

In 1977, Wendell T. Robie (1895-1984), the president of the Western States Trail Foundation and the director of the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup), decided that it was time to add a runner division to his famous Ride. For more than two decades this 100-mile endurance horse race had been held on the famous trail in the California Sierra. Could ultrarunners also race the course?

Robie had previously helped seven soldiers successfully complete the course on foot in 1972 (See Forgotten First Finishers), the first to do so, and had been pleased that Gordy Ainsleigh had been the first to finish the trail in under 24-hours in 1974. (See Episode 66). In addition, dozens of people had backpacked the trail since then, and a couple others had tried to run the course solo during the Ride. Robie believed it was time to organize a foot race on “his trail” for the first time.

This first Western States 100 in 1977 was hastily organized by riders, not runners. There was no consultation with the existing well-established ultrarunning sport at that time. Practices were put in place that mostly mirrored the endurance horse sport such as mandatory medical checks, but did not use the existing ultrarunning practice of setting up aid stations. The event would be held with nearly 200 riders and horses also competing on the course at the same time as the runners. The day would turn out to be perhaps the hottest ever for the historic race. The risks were extremely high for this small rookie running race staff and some rather naïve runners. Who were the runners who turned out for this historic first race? Did they have the experience to finish or just survive?

|

Race Organization

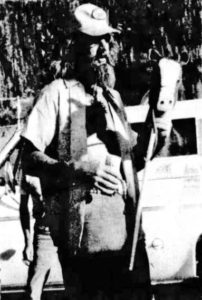

On Robie’s race staff was Gordy Ainsleigh, of nearby Meadow Vista, California. He was perhaps the most experienced runner in on the staff with some cross-country running experience. He had also run in some Ride & Tie events and of course had run the course solo three years earlier.

Ainsleigh had hoped to get the race director job from Robie and talked about putting in a qualifier requirement that the runners had to have completed a marathon in at most 3:15. He said, “We don’t want anyone who isn’t a good runner.” Thankfully, that requirement was not put in place. Ainsleigh did not have the organizational skills to put together a race and was not the race founder. Robie was the man in charge for the 1977 race and gave the race director job to Curt Sproul.

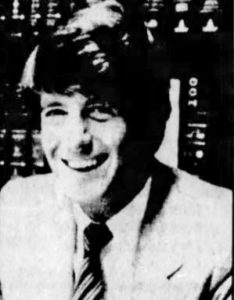

Curt Sproul

Curt Sproul, born into privilege, received his love for the outdoors from his parents. His father was also an attorney, an outdoors enthusiast and environmentalist, who frequently took his family on trips to Yosemite National Park and camping trips to Wyoming. His mother had once climbed to Everest Base Camp.

Sproul’s wife, Mo, was originally from San Francisco. Her father was an attorney and the president of the San Francisco Opera Association. The Sprouls met and married when both attending UC Berkley. They both would become very important contributors toward the founding and growth of Western States 100.

Race Planning

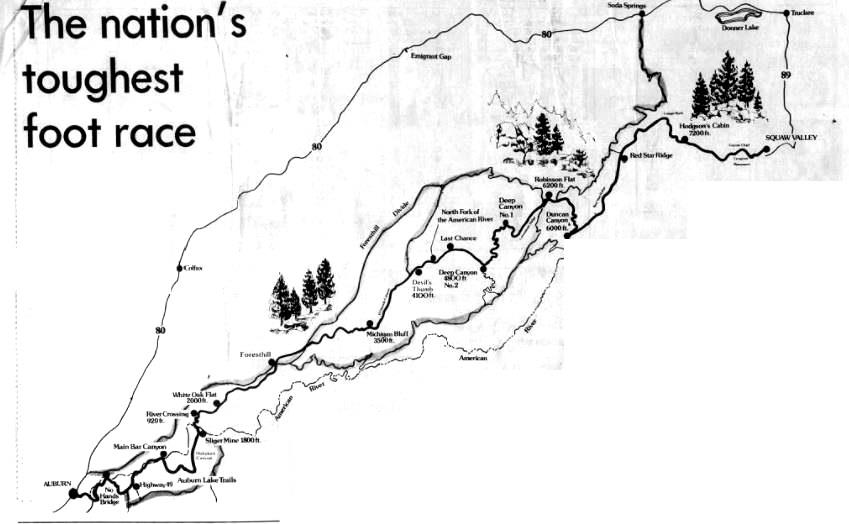

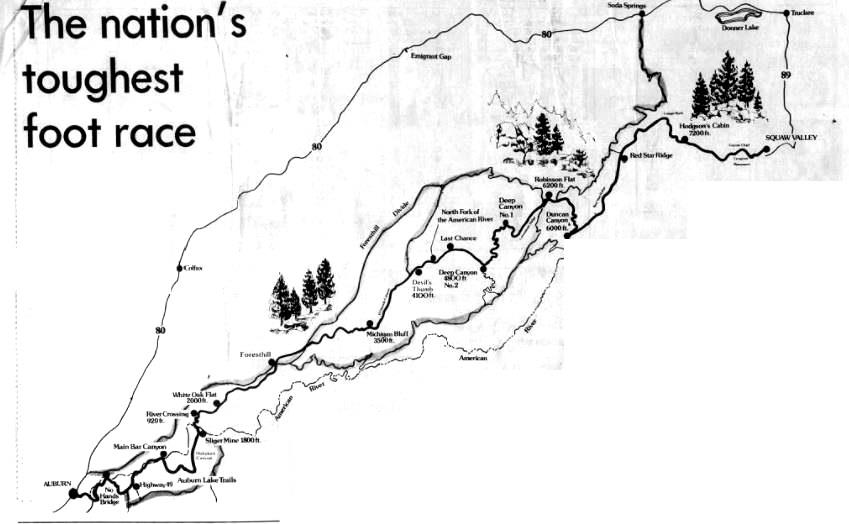

Four horse inspection stations would be utilized as runner checkpoints and water stations. They were very far apart for the runners at Robinson Flat (mile 33), Devils Thumb (mile 50), Michigan Bluff (mile 68) and White Oak Flat (mile 80). No traditional aid stations were provided for the runners ahead of time. The rookie race staff had no idea about the danger they were putting the runners in. Runners would have to drink from streams and provide their own food delivered to checkpoints in drop bags. Many did not. The emphasis that year was still mainly on the horses and riders. The runners participating were mostly an afterthought and were on their own.

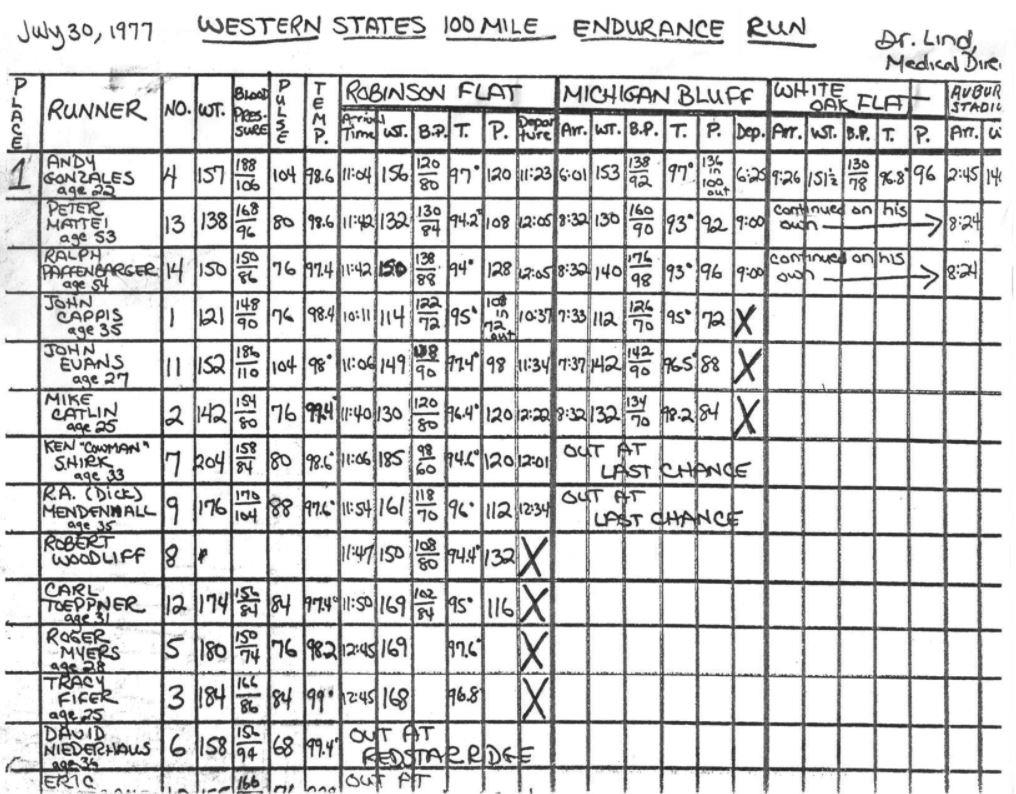

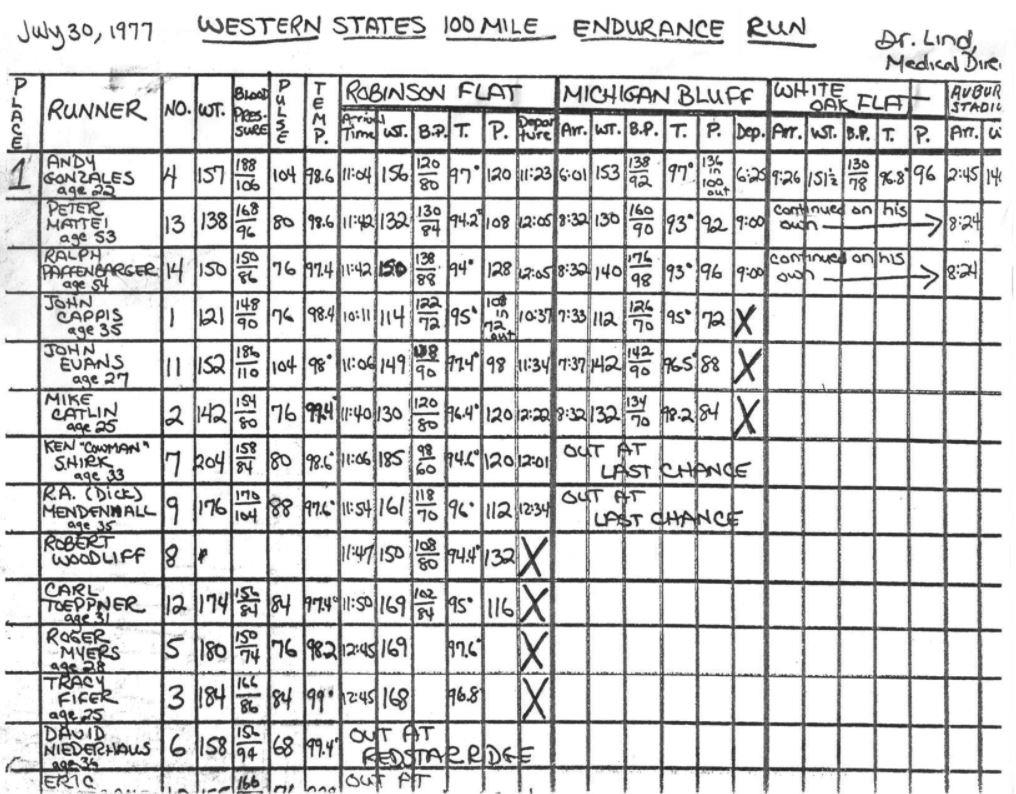

Medical students under the direction of Dr. Robert H. Lind (1934-2016), a physician at the Roseville Community Hospital, would check the health of runners and riders as they came through the four checkpoints. They checked blood pressure, pulse and weight. Lind and the medical students were inexperienced in checking ultra-distance runners, with a lack of understanding what to expect. They did not yet understand the dangers of electrolyte imbalance and hyponatermia.

Lind said, “I don’t understand how they can do this physically.” He also added, without any understanding of past ultrarunning history, “This is the hardest race on the face of the earth. It embodies nearly every hazard known in long distance running, including heat, fatigue, altitude and fluid loss.”

Western States Race Announcement

The Runners

What kind of runners were attracted to run this difficult race?

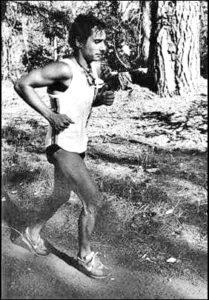

Andy Gonzales

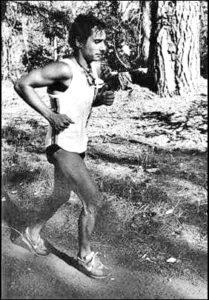

Gonzales ran his best mile time of 4:24 at an all-comers meet for the military branches held at Salano College at Fairfield Community College. His fame had spread and his competition could not keep up with him. He won, but did not enjoy running on the track. He wanted to be on the trails.

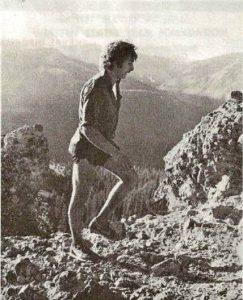

He had a favorite training trail in his hometown of Colfax, California, called Steven’s Trail. It was 3.8 rugged miles down to the North Fork of the American River and 3.8 miles back, climbing 1,200 feet. The trail had very little shade and was terrifying for hikers because it ran close to cliffs. He loved that trail and called running his “girlfriend.”

Before hearing about the 1977 race, Gonzales had a set goal to run the Western States Trail solo with the horses in 1978, just like Ainsleigh had done in 1974. He had been training to build up his ultra-distance strength by doing some long 50-mile runs. For other days, he typically would get up at 5 a.m., run 10 miles, and in the afternoon add another 15 miles, many times on Stevens Trail. He was asked if the heat of the canyons bothered him. “No. Look at the African runners. They run at home in extremely hot weather. They come here, run in cooler weather, and beat us.”

A week before the 1977 Western States 100, Gonzales still had not heard that a running race would be held and was not yet signed up.

Shirk started ultrarunning in 1976 when he ran the 72 miles around Lake Tahoe. He later entered another race, signed up as Cowman, and competed wearing horns. The name stuck. He tried a solo run on the Western States Trail during the 1976 Tevis Cup and completed the course in 24:20. He felt confident that he could win the inaugural 1977 race. “Living up at Tahoe, I’m used to high altitudes and I run in rough terrain almost every day. I’ve trained in this area for a long time. Depending on the weather and what happens on the trail, I’m hoping to run it in around 22 hours.”

Bob Woodliff

John Cappis

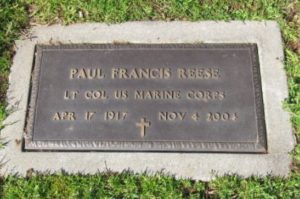

Peter Mattei, Ralph Paffenbarger, and Paul Reese

Three veteran ultrarunning buddies were among the entrants who were unknown to the rookie race staff and other entrants who were not yet informed about ultrarunning. These three would make a significant impact on early Western States 100 history.

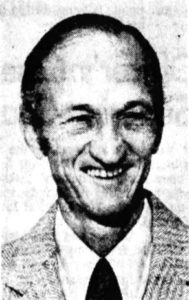

During the 1970s, Paffenbarger was published about the relationship between a sedentary life and heart disease. He eventually was able to show that with regular exercise, coronary death rates were reduced by up to 33 percent. His finding would help launch the aerobic exercise movement of the 1980s. He believed that for each hour of physical activity, a person gained an extra 2-3 hours of life. Paffenbarger took up competitive marathon running in 1968 at the age of 46 and progressed to an impressive time of 3:06:58. He took up ultrarunning in 1970 and finished 6th in the 1971 50-mile National Championship held at Rocklin, California with a speedy time of 6:13:41.

The Three Experienced Ultrarunners Sign Up

During the early 1970s, Mattei, Paffenbarger, and Reese had finished a road loop 100-miler, the Camellia 100 that was held each year in the Sacramento area. Mattei finished the 1971 version with a time of 20:56:30 when Jose Cortez and Natalie Cullimore set the American 100-mile records (see episode 64). In 1972, Paffenbarger and Reese also ran the Camellia 100. That year the race was held on a three-mile loop at the California Expo in Sacramento. The two battled closely at the 90 mile mark. Paffenbarger finished in 16:42:58 and Reese in 17:15:34, both very elite times. Earlier in 1969 they ran a three-day version of the 100-miler, 33 miles per day. Reese was hit by a car during that race.

Two weeks before the 1977 Western States 100, Mattei, 53, called up running buddy Reese, age 60, and tried to persuade him to enter the race and run as a trio with Paffenbarger, age 54. The phone call sounded like this, “Paul, I know you and Paff have run Pike’s Peak, and the 72 miles around Lake Tahoe, and a 100 miler. I’ve got one now that will make all that look like sissy stuff, and I want you to run it with Paff and me.” Mattei described the rugged Western States Trail to Reese.

Reese recalled, “Despite Peter’s coaxing, cajoling, and cussing, and despite realizing I’d not satisfy my curiosity over how I’d fair on this safari, I refused to enter, explaining to Peter that I was committed to two upcoming marathons, Crater Lake and Silver State. Finally, we compromised by my agreeing to only run the first 33 miles to Robinson Flat with them as a workout.

Gonzales Enters Last Minute

Two days before the first Western States 100, Gonzales was going for a run on Steven’s Trail when a mailman warned him about fire along the trail. So Gonzales instead decided to run east and came upon his friend, Gordy Ainsleigh, who was changing a flat tire on his car, on Placer Hill Road. Gonzales had known Ainsleigh since high school days when Ainsleigh would meet students at the school to go for runs on the cross-country trail. Gonzales stopped to talk with Ainsleigh who asked, “How would you like to run 100 miles tomorrow?” Seeing his surprise, Ainsleigh backed that down and suggested that Gonzales try to only run the first 33 miles. Ainsleigh did not think Gonzales had the ultrarunning training to go the distance.

Indeed, at that point Gonzales had not even run a marathon. He was just a mountain runner who as he put it, “chased women and drank beer.” On the next day Gonzales hitched a ride with Ainsleigh to head for Squaw Valley. “I had five bucks on me, a bag of green apples, and a tube of biscuits. I packed up my sleeping bag.” On the way, Ainsleigh told him that Cowman Shirk was going to win the race.

Prerace

When Gonzales saw the other runners determined to run the 100 miles, he because somewhat intimidated. A race briefing was held that afternoon, conducted by Robie, assisted by Sproul and Ainsleigh.

Some of the younger runners, seeing old runners Mattei, Paffenbarger, and Reese, scoffed at their chances to finish. They did not know that those three were by far the most experienced and accomplished ultrarunners in the field.

Ainsleigh went over the course and its profile. The course went up and over Squaw Pass, to Little American Valley, Hodgson’s Cabin, Red Star Ridge, the north border of French Meadows Game refuge, Robinson Flatt, and to Last Chance via Cavanaugh Ridge. The total descent was believed to be 15,250 feet with a total climb of 9,500 feet. (A few years later the course was measured and discovered to be only 89 miles.) At the briefing it was remarked, “We try to mark the Trail, but the bears keep destroying the markings.” Medical checks of the runners were also conducted at the briefing.

The runners spent the night before the race sleeping under the stars in their sleeping bags. Gonzales was next to Mike Catlin (1952-), a graduate student at U.C. Davis who was studying exercise physiology. “We laid there the night before drinking beer, wondering what we were getting ourselves into. It was pitch dark and the stars were in full bloom. We talked. We were both a little anxious and nervous. Basically, we did not know what we were doing.”

The Start

The runners were mostly dressed in nylon shorts, T-shirts, windbreakers, and running shoes. Most of them started off carrying flashlights. Gonzales did not carry a flashlight and only wore a singlet, a plaid button-down shirt, and Speedo swimming shorts. He never wore socks when he ran and did not during the 1977 race.

Reese commented, “I started the 2,400-foot ascent from Squaw Valley and the unfolding of many lessons. First, and indelibly inscribed, was the arduous effort required to keep moving. The heat became intense and stifled breathing. The water was scarce. At one stretch in 100+ degrees heat, I was four hours without water. The altitude, ascents and descents were problems.”

The narrow sections of the course became crowded with horses and the runners. If a runner or rider wanted to pass, they would yell “Trail.”

Runners Drop out in the Heat

Mo Sproul had the duty of trying to keep track of runners and assisted Dr. Lind with their medical data. She said, “We had no checkpoint between Squaw Valley and Robinson Flat, which is about 30 miles—no water, no anything. Those of us who were trying to help the runners were a moving aid station and would produce for them the supplies they brought. This was before Camelbacks and plastic water bottles. One guy was carrying an Aunt Jemima syrup bottle for water; most people didn’t carry any, and we didn’t know what needed to be carried. We had scales and saw that there were precipitous drops in weight from many of the runners, and by Michigan Bluff.”

Nearly half of the field dropped out by Robinson Flat at mile 33 including Woodliff. Major Neiderhaus was also among the early drops, only making it to mile 27. Many had gone out too fast. When Gonzales arrived at Robinson Flat, he was feeling good and decided not to stop there as Ainsleigh had suggested, and go on to run the entire race. He then started to catch up and pass runners.

Near Last Chance, at mile 48, Gonzales caught up with Cowman Shirk who was sitting down by the trail not looking very good along with Dick Mendenhall (1943-), age 35, of Oklahoma City. They looked at him and said, “whoever you are, keep going, you have a chance to win.” Gonzales moved into first place with a fire now in his belly.

During that year, there were not too many spectators along the course. But Gonzales would always wave, stop, and shake their hand. Word got out that he was coming and more came out to greet him.

Shirk and Mendenhall dropped out at Last Chance. Both Cowman and Mendenhall were suffering from dehydration. Cowman had lost an astonishing 20 pounds during the run, going from 204 to 184 pounds. Mendenhall has lost 15 pounds. After this inaugural race, Dr. Lind analyzed the weight-loss of those that did not finish and determined that run performance was significantly affected as when the runners lost 7% or more of their body weight. And thus, was established the 7% rule used for many years after that in 100-miles ultras. Gonzales was cruising well and initially only experienced a 3% drop in weight.

Three more runners were out of the race at Michigan Bluff at 68 miles because of the terrific heat, including Catlin, Cappis, and John Evans (1949-) of Vallecito, California. All would get their finish the next year. (Cappis would later help dream up the original Hardrock 100 course.)

That left just three runners in the race, Gonzales, and the two veterans, Mattei and Paffenbarger. At about mile 65, Gonzales had to step over horses that were exhausted, laying in the trail. He was also really struggling at that point. As he was stumbling along out of water, he came upon an old rancher sitting by his camper with his dog. The old man thought that Gonzales was crazy and offered him two cold beers, which he gladly drank. Feeling greatly revived, Gonzales continued on his run toward Foresthill. At Foresthill, in dire straits without water again, he was experiencing hallucinations. He went up to a random house, grabbed a hose, and with his chapped lips, drank some warm water. It was not until later in the race that the staff, including Doctor Lind, realized that the runners needed aid and set up an aid station for them during the last ten miles.

Running at Night

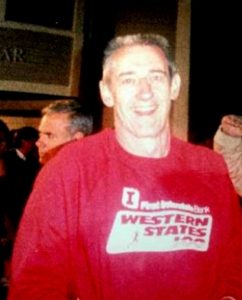

He made his way to the fairgrounds finish in Auburn with plenty of energy. He could hear an announcement over the load speaker informing everyone that the first runner was arriving. Many of the spectators still did not know that there were runners on the course.

The Finish

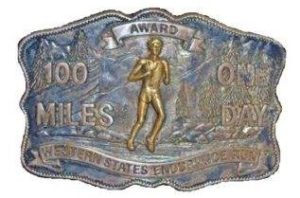

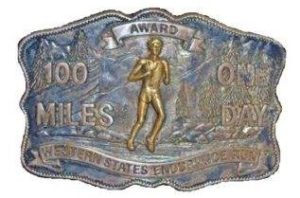

Gonzales became the first official Western States 100 finisher in history and established the course record in 22:57:00. Robie greeted him holding a cigar. A full stadium of riders and spectators cheered his finish. Ainsleigh was surprised to see him win. For Gonzales, it was a dream come true. “I wanted to become a running champion. I had dreamed of it day and night for years. The 100-miler turned out to be my cup of tea.”

Because of the official 24-hour cutoff that year, Gonzales was the only official finisher among the runners. The two veteran ultrarunners, who the younger runners doubted, Mattei and Paffenbarger, ran the entire way together. They had missed the previous checkpoint cutoff, but were given permission to continue together unofficially on their own with no support from the race staff. They both reached the finish in 28:36. It was said that these two finished due to their power of mental attitude which was the driving force that carried them through all the obstacles. (For some reason these two were later given official finishes along Ainsleigh and Shirk who finished the course solo before the race was founded in 1977. But sadly, the first seven soldier finishers of 1972 still have not been recognized as finishers in results). The solid slower times accomplished by Mattei and Paffenbarger helped race organizers consider extending the finish cutoff time the next year to 30 hours.

What Happened to the First Three Finishers of Western States 100?

Ralph Paffenbarger went on to finish four more Western States 100s and finished the Comrades Marathon (54 miles) in 1989 at the age of 66. In 1996 he received the first International Olympic Committee prize for sport science. He ran the Boston Marathon 22 times during his life and finished a total of 150 marathons and ultras. In 2007, he died from heart failure at the age of 84.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Mar 9, 1969, Mar 27, Jun 30, 1970, Aug 31, Dec 5, 1972, Feb 27, 1973, Sep 17, 1976, Jul 28, Aug 1, 18, Sep 15, Nov 24, 1977, Jun 1, 25, 1981, Nov 10, 2004, Apr 17, 2016

- Auburn Journal (California), Aug 31, Sep 7, Nov 23, 1972, Jan 9, 1974, Jun 24, Jul 1, 18, 25, Aug 3, 1977, Jun 28, 1978, May 4, 1979, Jan 29, 1986

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), Feb 13, 1970, Jul 4, 1993

- The Santa Fe New Mexican (New Mexico), Apr 27, 1975

- Albuquerque Journal (New Mexico), Mar 23, 1977

- NorCal Running Review No. 29

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), Aug 1, 1977

- The New York Times (New York), Jul 5, 1982

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Nov 1983

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Dec 8, 1985

- The Napa Valley Register (California), Jan 9, 1998

- The Los Angeles Times (California), Jul 14, 2007

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run Trustee for 30 years.

- 2014 Western States history presentation by Shannon Yewell Weil at the 2014 Western States Training Weekend. This Will Never Catch On: The birth of an Icon

- 2021 Interview with Andy Gonzales

- Shannon Yewell Weil, Strike a Long Trot: Legendary Horsewoman Linda Tellington-Jones

- Shannon Yewell Weil, Sacramental Running Association, HOF Speech