Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:05 — 26.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

This is a bonus episode about the Fort Meade races covered in episode 75.

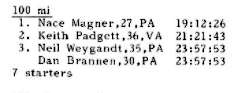

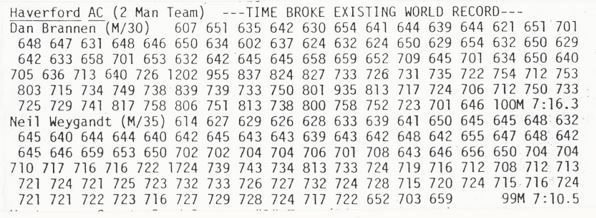

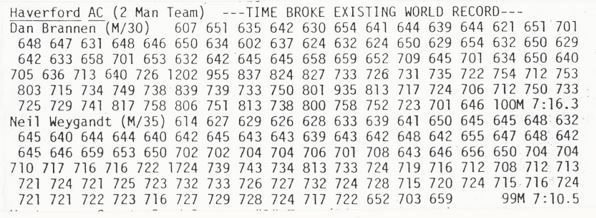

By the early 1980s, a few ultrarunners had tried to see how far they could go in 24-hours with just a two-man team. The known world record was 193 miles. During that time, the Philadelphia area was the home of many great roadrunners, with much credit to Browning Ross who organized numerous competitive races in the region for years. In 1983, two elite ultrarunners in America became inspired to try to break the world two-man 24-hour record on that track at Fort Meade in Maryland. These ultrarunners were Neil Weygandt and Dan Brannen.

Neil Weygandt

Weygandt ran cross country at Haverford High School and became their top runner and team captain. In 1962 at the age of fifteen, he met future ultrarunning great Tom Osler (see episode 67), who was 22 at the time. Weygandt started to go on long training runs with Osler, beginning a life-long friendship and mentorship.

From 1968 to 1971 Wegandt was a member of various track clubs that would run in races against other clubs. He and Osler competed together and frequently won in road races up to 17 miles long. From 1971-73 he worked with the Road Runners of America as a Vice President over the Eastern United States. In 1977, he began to run ultras, with the Metropolitan 50-miler in Central Park, finishing in 6:39.

In 1983, he was living in Ardmore, Pennsylvania and a member of the Haverford Athletic Association along with Dan Brannen.

Dan Brannen

In high school Brannen was required to participate in an athletic extra-curricular activity. He explained, “I was a shrimpy little kid. I played little league baseball, but I wasn’t particularly athletic or coordinated. One of the sophomores who came in to give the orientation, said, ‘If you can’t do anything else, go out for cross-country. So I did, my freshman year despite the fact that I was terrible at it.” He couldn’t run their 1.6-mile course without walking up a hill.

During his senior year, a new coach. Larry Simmons (1942-2004), a successful distance runner and racewalker took over the team. He lit a fire into the team and into Brannen who’s course times dramatically fell resulting into his promotion finally to the varsity team. His rapid success turned him into a runner for life.

Brannen went to Bucknell University in Central Pennsylvania and got in on the ground-floor of a new cross-country team. His coach, Art Gulden (1942-2001) developed into a highly successful running program at Bucknell. Brannen continued to improve under his tutelage and recalled, “Each year Gulden was able to recruit faster and faster high school runners. They included state champions and it was very competitive. I was able to stay with the second tier of those guys. One of the best feelings I had about myself was when I was running and keeping up with state champions.”

Brannen ran a few marathons during college, graduated in 1975, and joined the well-established road-racing scene in the Philadelphia and New Jersey area. He was a self-described “running bum,” and lived with his parents for many years as he concentrated on his running passion. His weekly mileage would average about 100-120 miles per week. His personal best marathon occurred at the 1979 Boston Marathon which he ran in 2:31:13. He was intoxicated with distance running and it evolved into a true career. Part-time he would work editing research manuscripts which enhanced his writing skills. He also coached cross country at his former high school.

“One of the prime organizers in the area was Browning Ross who was a great Villanova runner and Olympian. He also founded the Road Runners Club of America and started the Long Distance Log which was the very first running magazine. I would go over to South Jersey and met Ed Dodd, Tom Osler and Neil Weygandt in those races.”

Brannen ventured into the short ultrarunning races in 1978 by running the Knickerbocker 60 km in Central Park and ran in a few others the next year.

1980 JFK 50

In 1980 in ran 50 miles for the first time at JFK 50 in Maryland. To convince himself that he could do well, he ran two sub-3-hour marathons on back-to-back days leading up to the race. He ran 2:58 at Kane, Pennsylvania on a Saturday and 2:57 at Johnstown, Pennsylvania the next day.

He went to JFK thinking that he might have a good chance to win. His specialty was gnarly, rocky, technical trails. He knew that he could stay with people who were faster than him on roads and hoped to keep up with the previous year’s champion, Bill Lawder (1947-) of New Jersey.

Brannen’s JFK 50 start did not go smoothly.

Brannen continued on, running an ideal race. Two others ahead of him soon dropped out and he went into the lead at about mile 20. He was later passed by Lawder on the C&O Towpath but caught him on the final long road uphill toward the finish and won by nine minutes.

During the next few years, Brannen branched out and started organizing and race directed classic early ultras including the Great Philadelphia to Atlantic City race and the Haverford indoor 24-hour and 48-hour races. His first 100-miler was at Fort Meade in 1981 which he used as a qualifier for a six-day race. By 1983 he was well established in ultrarunning.

The Idea for the Relay

Brannen and Weygandt developed a strong friendship. Brannen explained, “We were members of the Haverford Athletic Club during the heyday of that club during the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. We trained together a lot. Our regular club run was a Wednesday evening run through the hills next to Villanova. It was like ‘last man standing.’ They were 15-mile hilly runs. I remember finishing some of those runs and looking at the guys around me including Neil saying, ‘gee, we should have been wearing a bib.’”

The 24-hour relay races fascinated Brannen. He had been aware for many years about the 24-hour relay which during the 1970s was a popular event nationwide. He followed the progression of the records of the 10-person relay and was amazed at some of the distances achieved as they kept going further and further. He followed the news of a team in New Zealand that broke the world relay record with an interesting approach. “They made a pact. Any runner on the team that ran a mile in more than 5 minutes was out. They finished with about six runners. That was the way they maintained their speed and I was so impressed. I came across the news that there was a two-man 24-hour relay that accomplished 193 miles and one of they key members was an ultrarunner. T.J. Key from San Diego. I contacted him and he confirmed the world-record accomplishment.”

They we well-prepared, both in great shape, and brought an excellent crew, Brannen’s sister Mary and his best friend Paul Caulfield. They were well stocked with plenty of clothing changes, beach chairs, towels, ice, beverages, and food.

The Two-Man Relay

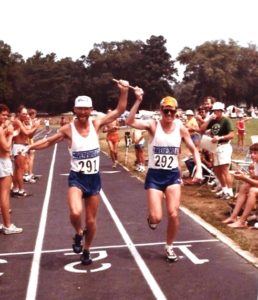

Weygandt and Brannen began and passed a small wooden baton back and forth. Brannen recalled, “We got going and got into a groove early on and seemed to be holding our pace pretty well.”

They did run ran very well averaging about a 6:45-mile-minute pace until about halfway, shortly after midnight. “We ran a couple of laps where we started to slow and really feel like it was becoming a drag and we stopped experiencing the fun of the challenge.”

The Low Point

Brannen recalled, “Our handlers said, ‘look, both of you just sit down.’ They got us to eat more than we previously could eat during our short 7-minute stops. We were off the track for just under 15 minutes. And then Neil just came back to life. He got his spirit back and went back out there. It took me one or two miles to get back into my groove.”

The Finish

For the last six hours Brannen had a strange feeling in his legs unlike anything he had ever felt in his entire running career because of the on again and off again. He told his crew that his legs were “singing.” They were not in pain, but they were vibrating and seemed to be humming loudly.

To Brannen, it was one of his most memorable ultrarunning experiences. For

a day, they believed they were world record holders which gave them a wonderful feeling. Brannen fondly recalled, “That feeling has lasted throughout my life, even though we found out within a day after we did it, that the same weekend about 12 hour earlier, two South Africans had gone farther.”

Yes, Bruce Matthews and Graeme Dacomb also ran a two-man relay and reached 201 miles claiming the world record before them. Matthews, now of New Zealand, added, “Whilst making our attempt on the 197-mile record, we offered our bodies to a group of students doing a scientific paper to gain a Sports Science degree. We had weight checks every hour, blood drawn every hour, all food and drink intake measured, all output measured, rectal core temperature taken hourly and a psychological questionnaire taken every three hours.”

Prior to that historic relay, Brannen and Weygandt had been good friends and running buddies. They crewed each other at races. But the relay experience had a deep impact on them and bonded them together, which is surprising because they had zero teammate interactions for the entire 24 hours except for the 15 minutes when their race was following apart and the final couple laps. Otherwise, their interactions were just for fleeting seconds of 100 different handoffs.

Neil Weygandt’s Future Years

Brannen said commented about Weygandt. “Neil is a great guy. A really unassuming, “salt of the earth” kind of guy. I can’t imagine anyone could ever find a reason to be upset or angry with him. He is just a wonderful down-to-earth simple, friendly guy.” Local runners remembered that “win, lose, or tie, Neil would somehow find a way to congratulate your effort and downplay his.”

Dan Brannen’s Future Years

Brannen is one of the very few that successfully made running his career. He did it by establishing a running race timing business and for years timed races every weekend. He also became a course certifier and was the course manager for the 1988 US Olympic Trials Marathon in New Jersey along with other very prominent races. He became an expert at logistics and operations for road races, triathlons, and cycling races. In 2021 Brannen continues to run, and his passion is competing in adventure racing including cycling, canoeing, and orienteering.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Source:

- Telegraph-Forum (Bucyrus, Ohio), May 9, 1972

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Dec 19, 1966, Aug 8, 1983

- The Lompoc Record (California), Jun 15, 1983

- Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), Apr 4, 1967

- Emails and interviews with Dan Brannen, March 2021 and April 2021

- “WORLD RECORD HOLDER RETIRES FROM THE BOSTON MARATHON AFTER 45 CONSECUTIVE FINISHES”

- Runners World, “Neil Weygandt, King of the Marathon Streakers”

- email from Bruce Matthews, November, 2021