Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:29 — 27.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

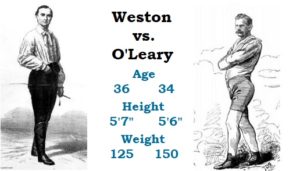

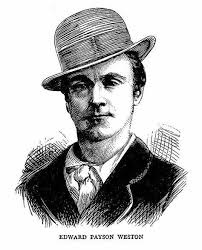

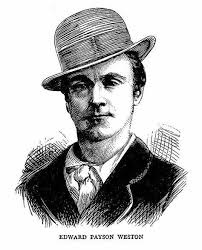

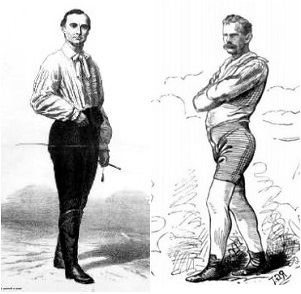

In 1875, Edward Payson Weston was the most famous ultrarunner (pedestrian) in the world. Like a heavyweight boxing champion dodging his competition to keep his crown, he avoided repeated challenges to race against the up-and-comer, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago, Illinois. The two were the most famous American athletes in 1875.

In 1875, Edward Payson Weston was the most famous ultrarunner (pedestrian) in the world. Like a heavyweight boxing champion dodging his competition to keep his crown, he avoided repeated challenges to race against the up-and-comer, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago, Illinois. The two were the most famous American athletes in 1875.

| Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

Weston vs. O’Leary – Finally

Similarly, in Mobile, Alabama: “Suppose these men had ploughs, wouldn’t they add something in this way to the wealth of the world?”

Pre-Race

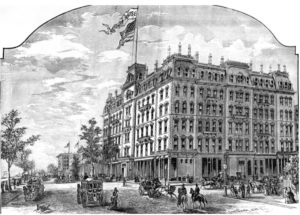

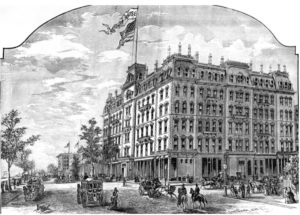

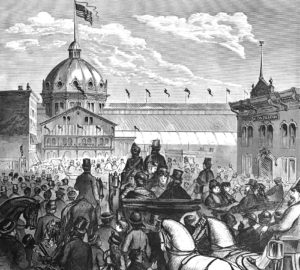

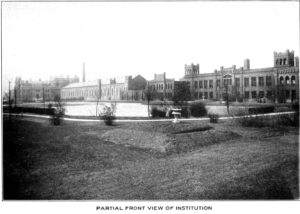

Weston arrived in Chicago three days before the race with his two black servants and stayed at the luxurious Gardner House, next to the Exposition Building on the Lake Michigan lakefront. It was reported, “He is in good condition and confident of success. O’Leary also is in excellent trim, and confident of victory as his opponent. The contest will no doubt prove very exciting.” Wagering was heavy with Weston being a slight favorite.

The Chicago Tribune gave a pre-race commentary about the two pedestrians. “O’Leary has made some excellent feats, and has but one failure to his credit, while Weston, with also a good record at times, has a considerable number of bad fizzles on his list of attempts. Both men have before attempted the 500-mile walk, and both have succeeded. O’Leary made the distance in a little over 153 hours, while Weston covered the same ground in ten hours less. However, some doubt was cast on the accuracy of the timing and measurements which resulted.”

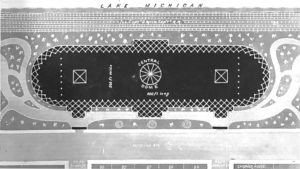

O’Leary visited Weston and talked over plans for the race. Weston inspected the track and gave his approval. Two separate tracks would be used, the outer six laps to a mile, and the inner, seven laps to a mile. Weston was offered his choice and he picked the inside track.

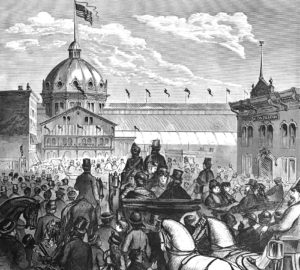

The Start

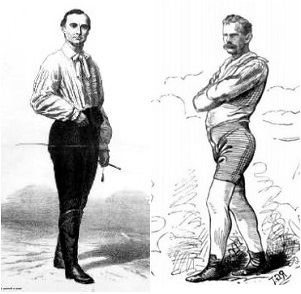

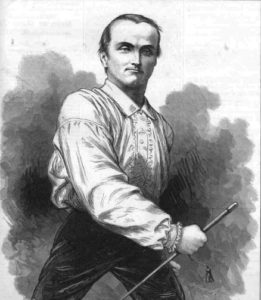

Weston arrived later and came up to the judges’ stand at midnight. O’Leary soon joined him, and a crowd gathered around to watch the start and gave loud applause. The two athletes shook hands and wished each other well. “Weston wore the black velvet suit he has used in his previous matches, knee pants, boots, a light linen hat, a silk ribbon thrown across his shoulders, white gloves, and carried a light whip in his hand. O’Leary wore white tights, a striped tunic, and light walking shoes. He wore no hat and carried a pine stick in each hand.” O’Leary’s wife stood near his track with a nervous look on her face.

William Buckingham Curtis (1837-1900) was the race referee. He was one of the most important proponents of organized athletics in the late 1800s in America and founded the New York Athletic Club and the Chicago Athletic Club.

Mayor Harvey Doolittle Colvin (1815-1892), the starter, gave a short speech. He hoped that the city would treat the visiting Weston well. “If our man can beat him, or course we shall be very happy, we wouldn’t like it to be done in any unfairness whatever.” The two walkers took their places on their tracks.

Mayor Colvin counted, “one, two, three” and off they went. The second six-day race in history began at 12:08:19 a.m. on November 15, 1875.

Day One

![]()

![]()

The walking styles of the two competitors were quite different. O’Leary walked straight, with a quick stride and bent arms. “He conveys the impression of walking nervously with more exertion than Weston and his crooked arm helps to give him an air of labor.” Weston seemed to drag his feet, then throw them, with a long swinging step, with his arms at his sides.” O’Leary held his head up, looking around him, while Weston always looked sharply down and saw nothing but the dirt ahead of him.

![]()

![]()

During that first evening, there was a surprising skirmish in the audience. Fifteen-year-old Albert Henry Morton (1860-1893) had recently escaped from the Bridwell House of Corrections and showed up to watch the race. A police officer noticed him in the crowd and approached to make the arrest. “Albert drew a razor and attempted to carve the officer. A well-directed blow with a club subjugated Albert.” He was taken before a judge and had 90 days added to his ten-month sentence for burglary and stealing a watch and chain. (Morton continued his life of crime for a couple years during his youth after being released from prison, but eventually became a respected businessman in the city. He died young from tuberculosis.)

O’Leary reached 100 miles in 20:58:21, with rests totaling about two and a half hours. At 110 miles, he was 20 miles ahead of Weston and retired to his room for a few hours’ sleep. At that point Weston went to his room at the Gardner House for five hours of sleep. With both men away from the track at 11:30 p.m., most of the crowd to left for the night.

Day Two

On the morning of day two, both of the determined walkers were back on the track by 4 a.m. and put in constant miles without any long rests during the day. Weston stopped for a supper break at 5:17 p.m. after reaching his 150th mile.

During the evening, a rumor was circulating around the city that Weston had “broken down” and had resigned from the race. People started to flock to the building to celebrate O’Leary’s victory. A reporter went to Gardner House to validate the report. Weston had just finished his supper and was angry about the false report. He stated that he was not thinking about quitting, that his physical condition was good and he was pleased with his progress.

Weston returned to the track after his supper and continued to walk all evening. He made efforts to please the audience with gestures, songs, imitating actors, and “other recreations.” He claimed that he never felt better and reached mile 168 by midnight. O’Leary stopped for the night at 10:30 p.m. after reaching mile 190. It was speculated that Weston was playing a “waiting game,” expecting that O’Leary would crumble by day four or five. But O’Leary had walked strongly that day and at no time showed any signs of exhaustion.

Day Three

During the morning, a man came into the building and handed a note to one of O’Leary’s handlers. It was a formal challenge for O’Leary to walk 150 miles against the man. “The challenge was consigned to the flames.”

The audience size grew each day. Reporters issued complaints that the race staff were providing them “abominable accommodations” being jammed into the crowd without seats, despite the free coverage they were giving in their papers about the event. They said, “It was impossible for newspaper men to make reports while hanging over a railing to which their chins barely reach.”

O’Leary extended his lead by five miles that day. The score at midnight was O’Leary 273 miles, Weston 247 miles.

Day Four

Mayor Covin put in an appearance during the day and walked with Weston around the track a few times. It was commented, “A few laps were sufficient to show that he does not shine with any particular brilliancy as a walker.”

At 11:40 p.m. O’Leary said as he passed the judges’ stand and shouted, “Gentlemen, I bid you all good night.” He had reached 350 miles. Weston continued until midnight, reaching 314 miles. Each day O’Leary was increasing his lead.

Day Five

Day Six

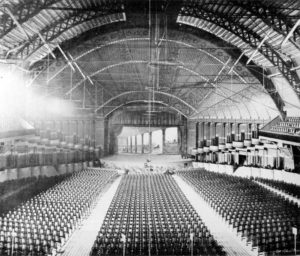

“The crowd was dense, sweeping hither and thither, shouting, yelling, or cheering. The crowd represented wealth, brains, thieves, gamblers, and roughs. Ladies were there in large numbers, but all had a terribly hard time of it in the ceaselessly moving and noisy throng.” It was amazing to see dignified gentlemen in neckties, standing next to those of the lower class, cheering together.

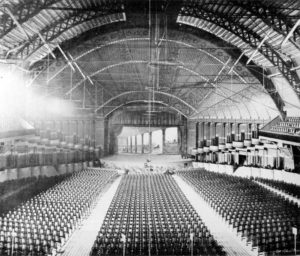

The police had trouble managing the crowd and at times were overwhelmed by mobs coming down on the track composed of gamblers, thieves, pickpockets, and rowdies. There was an estimated 8,000 people in the building, most of which were orderly working men with wives and children. Many boys and men climbed for high perches in the building trusses near the roof, on top of the large town clock and elevator. “Though the crowd made a great deal of noise, it was very good-natured, and though it felt pleased with O’Leary’s feat, it did not forget to heartily cheer the New York lad.”

At 7:55 p.m. O’Leary had reached his 488th mile, while Weston had only walked 14 miles so far that day and was at 439 miles. As O’Leary continued to close in on 500 miles, the crowd cheered loudly as he went by. He stopped at 8 p.m., was rubbed down and drank hot tea. Even though Weston was beat, he was encouraged on with cries of “bully boy” and “go in.” It was announced that O’Leary planned to walk past 500 miles and go as far as he could before midnight.

The Finish

The event was a great financial success, bringing in about $16,000 for the week, valued at $400,000 in today’s value. Later, O’Leary said that he and Weston divided the net gate proceeds, each receiving $5,500. They both became very wealthy. O’Leary would invest much of it back into the sport. Weston would spend most of it on an extravagant lifestyle, always spending more than he earned.

Post-Race

When asked about O’Leary, he said he was the fastest walker he had ever met, but he still believed he could beat him in a very long race, even though he did not this time. Months later, after Weston was frustrated with continual reminders about his defeat by O’Leary, he brought forth a new excuse that was never reported on during the race. He said that some Chicagoans had sprayed pepper in this face as he walked, and others threatened to shoot him. This was likely untrue and just sour grapes for not performing as well as he hoped.

O’Leary started to receive challenges from random unknown walkers, which he ignored. A rumor was going around that he and Weston were going to form a partnership and go on tour, but he said that report was false. He was willing to walk against him or any other man if the money was worth it, but at that time, he didn’t plan to compete for the next six months. He believed that someday he would compete in England.

Reaction to the Race

Also in Chicago, “Weston is used to defeat. His results have rarely, if ever, reached his expectations. Although he enjoys a national reputation as a ‘walkist’ and set out upon the present race with the assumption that an easy victory lay before him, was quite boastful and confident as to the result, he has been easily vanquished by a competitor who has hitherto had only a local reputation. O’Leary tramped and tramped steadily along, keeping to his work with steady persistence, while Weston joked, sung, chaffed with the spectators, and took delight in exhibiting himself.”

Six-Day Walks a Waste of Effort

In Wisconsin: “We cannot regard the performance as otherwise than a show conceived and conducted for money-making purposes. As a test of muscle and endurance, the exhibition was perhaps one degree above a prize fight.”

Anti-Westonism

In Chicago: “Weston would have beaten O’Leary if O’Leary hadn’t gone so far out of his way to beat him. Afterall, it is best that Weston didn’t spoil a glorious failure record by succeeding in what he undertook to do.”

O’Leary had proved that he was a worthy opponent for Weston and probably better. It was time to take this new popular sport internationally.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Interstate Exposition Building

- Gardner House

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Oct 30, Nov 16, 18, 1875

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois), Nov 6, 1875

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Nov 7, 12, 15-22, 1875

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Nov 12, 15-22, 1875

- The Mobile Daily Tribune (Alabama), Nov 12, 1875

- The Leavenworth Times (Kansas), Nov 14, 1875

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Nov 15, 1875

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Nov 25, 1875

- The Republican-Journal (Darlington, Wisconsin), Nov 26, 1875

- The Warrensburg Journal (Mississippi), Nov 26, 1875

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Nov 26, 1875

- The Fort Wayne Sentinel (Indiana), Nov 27, 1875

- The Clinton Public (Illinois), Dec 2, 1875

- The Semi-Weekly Advocate (Belleville, Illinois), Dec 3, 1875