Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:06 — 31.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

The Astley Belt quickly became the most sought-after trophy in ultrarunning. O’Leary was then the most famous runner in America and Great Britain, pushing aside the fleeting memory of Edward Payson Weston. As with any championship, want-a-be contenders came out of the woodwork. They coveted the shiny, heavy, gold and silver Astley Belt and wanted to see their own names engraved upon it. But more than anything, they also wanted the riches and the fame from adoring fans of the new endurance sport which was about to experience an explosion of popularity in both England and America.

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

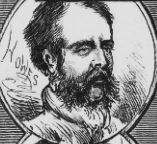

Challenger: William Howes

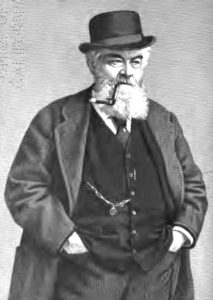

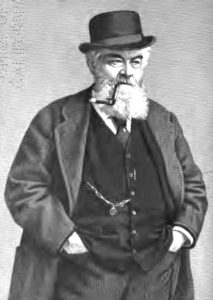

On the same day of O’Leary’s Astley Belt six-day victory, he received a challenge for the belt from William Howes (1839-), age 39, a waiter from Haggerston, England. Howes had been a very vocal critic of the Americans, O’Leary and Weston. He must have looked old because he was referred to as being “rather advanced in years.” He was 5’4” and had competed in running for many years.

Back in December 1876, O’Leary had experienced the first pedestrian defeat of his career against Howes in a 300-mile 72-hour race when O’Leary had to drop out mid-race because of sickness. Howes had accused O’Leary of faking the illness to delegitimize Howe’s victory. Then a month later, Howes anonymously tried to put together a race against O’Leary, Weston and himself. But then Howes experienced an injury, couldn’t participate, and was very mad that the race wasn’t postponed for him.

Howes Issue Challenge to O’Leary

O’Leary was required to accept any challenge within three months and defend the belt within 18 months, but he had no intention of staying in England with his family to race against the pesky Howes. Howes, who clearly dodged competition in the First Astley Belt Race, just one week later, on March 30, 1878, raced against ten others for 50 miles in the Agricultural Hall in London. Howes, won by two minutes and broke the world record with 7:57:54, the first to break the eight-hour barrier. (Later in the summer he would lower it further to 7:15:23 at Lillie Bridge).

Also, just three days after O’Leary’s victory, Weston, who had also pulled out of the Astley Belt race claiming illness, realizing the huge money that could be involved, issued his own challenge against O’Leary. Other challenges came from Brits, Henry Vaughan, William Corkey, and Blower Brown, all veterans of the First Astley Belt Race.

O’Leary Returns to America with the Belt

![]()

![]()

Challenger: John Hughes

Hughes began his running career in 1870 and embraced the nickname of “Lepper” because of his odd jumping gait. He successfully ran in many races up to ten miles over the years and then started to do long journey walks. As Weston and O’Leary started to pile up winning money, he wanted in on the action but couldn’t find a financial backer.

Hughes Seeks to Beat O’Leary

Clearly, Hughes was under-qualified to compete for the Belt. “He does not profess to be a great walker, but he claims that he could out-run any man in the world.” He claimed to be training a very improbable 40 miles a day. “All professional pedestrians are bitterly opposed to him. They say he is a fraud and brags too much to amount to anything.”

O’Leary Forced to Accept Hughes’ Challenge

O’Leary continued to ignore Hughes’ challenges, and challenges from British runners. One complained, “O’Leary has not accepted a single challenge since he became holder of the championship belt. All those who have challenged him, he appears to think beneath his notice.” O’Leary was blunt and said, that he had no desire of shirking his responsibility to defend his championship but objected to “fourth-rate pedestrians” making money off of his reputation.

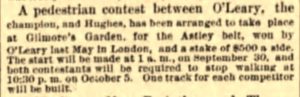

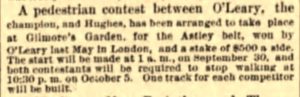

In July 1878, Sir John Astley in England, ruled that O’Leary must accept Hughes’ challenge or forfeit the Astley Belt and “Champion of the World” title. O’Leary decided to accept a challenge. Surely O’Leary knew Hughes would not be serious competition, but a defense of the Belt was needed according to the rules. Initially O’Leary made things difficult, stating that Hughes would need to cover half of the expenses and that no entrance fee would be charged to the public to watch.

Plans for the Second Astley Belt Race

In preparation for the match, in August 1878, Hughes claimed to have walked solo, 500 miles in 35 minutes less than six days at Newark, New Jersey. However, it was discovered that the track was seriously short, and he probably only walked about 300 miles.

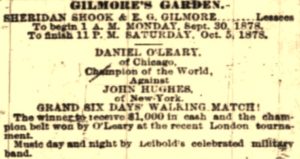

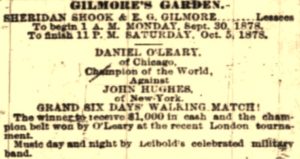

After several weeks of “somewhat acrimonious and even stormy discussions” between O’Leary and Hughes’ agents, articles of agreement were signed to race for the Second Astley Belt to be held in New York City, at Gilmore’s Garden, on September 30, 1878, with $1,000 going to the winner. “The party covering the greatest distance during the time by either running or walking without assistance is to be declared the winner.” Half of the gross proceeds of the gate money would be divided between the two, three-quarters to the winner. Sir John Astley and the Amateur Athletic Club of London would work with the athletic clubs of New York to oversee the event.

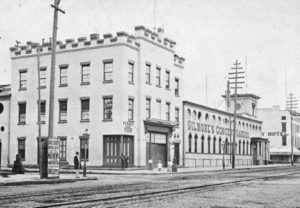

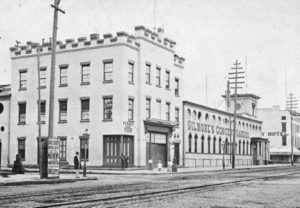

Gilmore’s Garden

Gilmore’s Garden was a venue that originally was constructed for P. T. Barnum’s Hippodrome in New York City, where the first six-day race in history was held in 1875 (see episode 95). William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) owned the property and after the circus vacated later that year, band leader Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892) leased the property for concerts, flower shows, beauty contests, dog shows, and boxing matches and renamed to Gilmore’s Concert Garden. A permanent roof was added around 1876. (Gilmore’s Garden became one of the most popular venues in the city and in May 1879, it would be renamed to Madison Square Garden and be significantly upgraded and outfitted with electric lights. The New York Life Building now stands on this historic block in New York City where so many six-day races were held.)

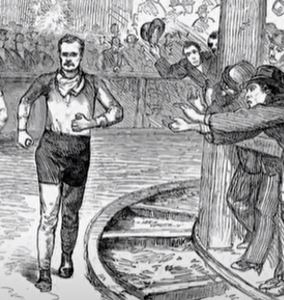

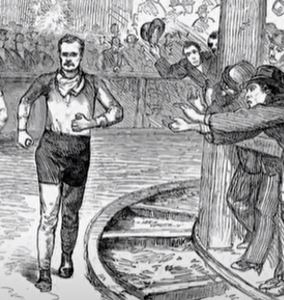

The Second Astley Belt Race

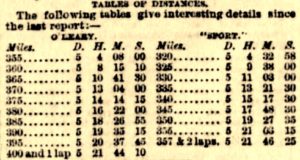

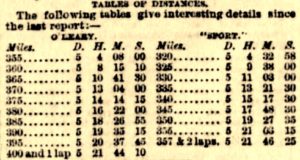

Two separate 2.5-feet wide tracks were laid down, the outer, eight laps to a mile and the inner, nine laps to a mile. O’Leary won a coin flip and chose the outer track. The surface was made of soft dirt about three inches deep rolled on top of asphalt. O’Leary would make use of a hat room where he put a comfortable cot and a cook stove. Hughes would use a little tent, also with a bed and stove. He would be helped by his wife and two children. The Garden arena included evergreens and flowering plants giving it a beautiful appearance. A grandstand used for concerts was left in place along with chairs, seats, and benches on the infield grass. Thick smoke would pour out into the building from the two stoves, filling it with a cloud, but they soon figured out how to divert it.

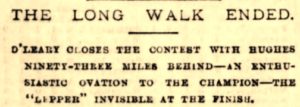

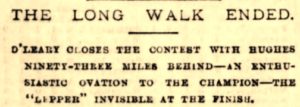

A day later, O’Leary said that Hughes was a “humbug” and criticized Sir John Astley for forcing him to compete against him. Critics said, “Hughes never displayed the slightest characteristics of a walker and slouched around the track with a shambling gait that did not even have the merit of covering the ground fast. The spectators saw in him a worn out and exhausted man who had struggled hard to win a fight in which he was overmatched.”

Yes, the Second Astley Belt Race for the Championship of the World was a mess, and an embarrassment. In England, the championship was called a fraud in the sport. “The distance covered was by no means long enough. If this is the best specimen of American mixture that can be produced, the sooner these contests die out the better.”

Challenges were immediately issued to O’Leary for the belt by other Americans, including Charles Harriman of Boston, and John Ennis of Chicago. O’Leary, learning from his mistake of wasting effort walking against inferiors replied, “I will melt the belt before I will compete against any man that has not a record of 500 miles in six days.”

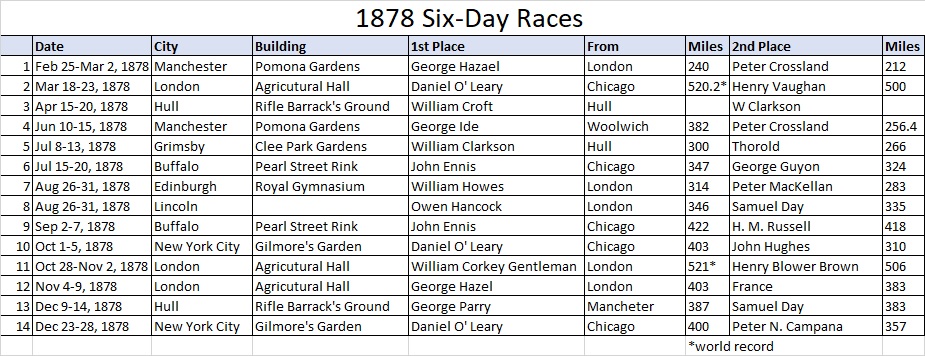

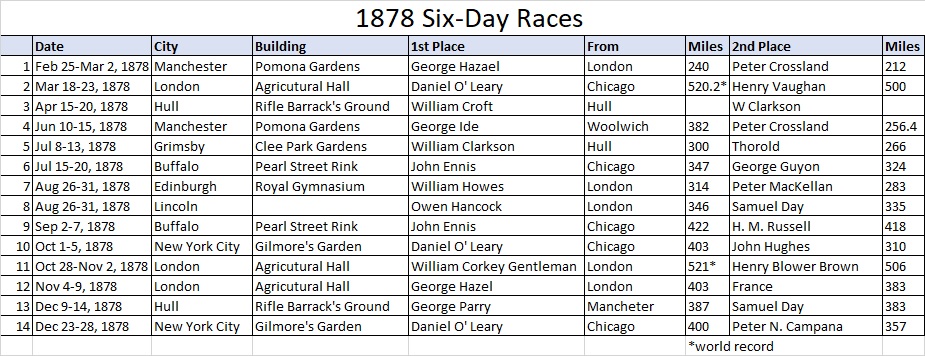

Other 1878 Six-Day Races

Other Six-Day races were conducted during 1878 in England where they were now more popular than in America. But most of the races were competed at a lower tier competitively, with no runners going over 400 miles. One race of note was held with 24 starters at the Pomona Gardens in Manchester. But the race limited the runners to 14 hours per day and the winner, George Ide, only reached 382 miles. In America, two six-day races were held at the Pearl Street Rink in Buffalo, New York, a city that had enthusiastically embraced Pedestrianism. John Ennis of Chicago won a match there with 422 miles.

English Astley Belt Race

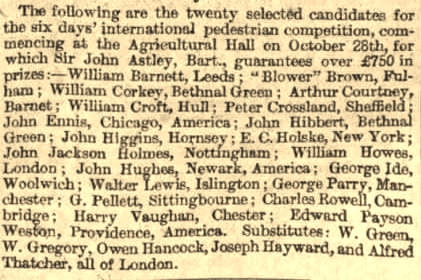

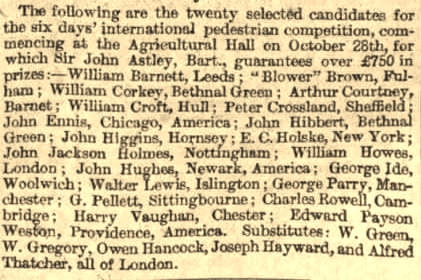

Plans for the English Astley Belt Race

The Championship of England race would be held in the Agricultural Hall in London. Rules and conditions for the race were nearly identical to the First Astley Belt Race with a few important exceptions. There would only be one track, not a separate one for Weston. “All will walk on one wide track, and any competitor may turn and go in the opposite direction at the completion of any mile.” Sleeping accommodations would be greatly improved. All races for this new challenge belt had to be held in London, which countered the problem that O’Leary was causing by insisting his challenges take place in America.

Not all were in favor of the event. “We are to be again treated to more disgusting sights. Such exhibition ought to be prohibited by law. They are a disgrace to humanity, reducing it to the state of a beast, with the look of a wild animal tramping wretchedly round and round a gloomy enclosure for the edification of an ignorant and gaping crowd. The quantity of harm wreaked by foolish enthusiasts like Sir John Astley, who pretend to a love of sport, and know nothing whatsoever of the mechanism or uses of the human body, is incalculable.”

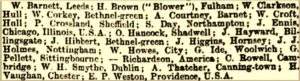

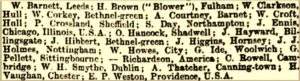

The Start

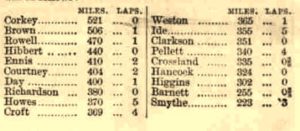

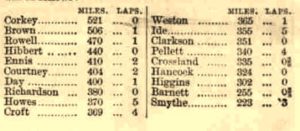

The race started at 1:05 a.m. on October 28, 1878 with 23 starters. Sir John Astley gave a speech and then ordered the men to start. Blower Brown (see bio in episode 106) quickly went into the lead clocking the first mile in a speedy 7:43 and reached 50 miles first, in 8:01:47. Most contestants ran and surprisingly, even Weston ran at times, “it being a series of short steps.” Weston refused to use the plain tent provided and would leave the hall to sleep in more luxurious accommodations. The race was highly competitive that evening in front of 8,000 spectators. After the first day the score was Peter Crossland 117 miles, William “Corkey” Gentleman 114, and Blower Brown 111. Weston was in 6th place with 101 miles. Eight of the 23 three starters reached 100 miles on day one, a significant improvement for British ultrarunners. After 48 hours the top three were Corkey (see bio in episode 106) with 204 miles, Brown and Crossland with 200. Vaughan, the favorite, wasn’t doing well because he had sprained an ankle during training when a dog had run in front of him and quit the race after two days.

The Finish

Corkey immediately issued a challenge to race O’Leary for the Astley Belt and said he would even pay for O’Leary’s expenses to travel to England for the match. Brown also issued his challenge and was willing to race in America.

Secondary English Six-Day Race

In all, at least 14 six-day races were held during 1878 in both Great Britain and America. To close off the year, O’Leary raced Peter Napoleon Campana for six days at Gilmore’s Garden in New York City. The story of Campana is another lesson to be weary of over-anxious ultrarunners seeking fame and fortune.

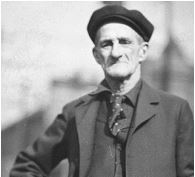

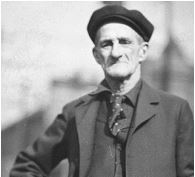

Peter Napoleon Campana

Peter Napoleon Campana (1836-1906), age 42, was a fireman from Bridgeport, Connecticut. His family came from France. As a youth he was very involved in athletics and received the nickname of “Young Sport.” While living in New York, he became a volunteer fireman and later when he moved to Connecticut was a peddler of nuts and fruit. Running fast was a passion and an extraordinary talent. By 1860 he was competing in races up to ten miles and was winning.

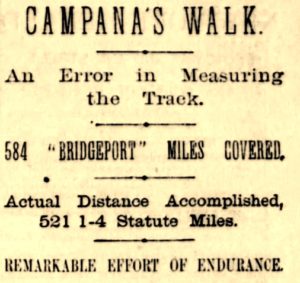

Campana Claims to Break the Six-Day World Record

O’Leary vs. Campana

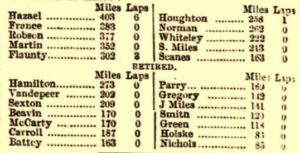

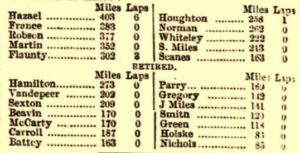

The race began on December 23, 1878, at Gilmore’s Garden in New York City under the direction of William B. Curtis. It was held with the same “go-as-you-please” rules established by Astley. Two separate tracks were used, nine laps to a mile and eight laps to a mile. They were the same tracks used in the recent Second Astley Belt Race. O’Leary set up his same sleeping quarters and used his same trainers as in the former race.

The Start

The race began at 1 a.m. “A stillness reigned in the vast building, which was only broken at intervals by the voice of the timekeeper as he recorded in a loud voice the number of laps, the miles, and the time of each competitor.” Campana wore a shirt with the word “Sport” written on the front. Both occasionally broke out into a run.

Of Campana it was written, “He is about five feet eight inches high, very muscular, and broad across the shoulders with a small waist. He has a very slouching gait, not so bad as Hughes, but without any of the style or grace of O’Leary. His most natural gait is a little dogtrot about five to six miles an hour, and this is his favorite method of getting along.”

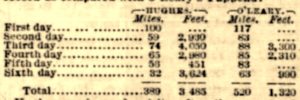

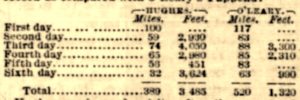

After ten hours Campana had built up an eight-mile lead due to O’Leary taking a two-hour break early on. After the first day, Campana held a surprising lead, 90 miles to 83 for O’Leary.

Running in Smoke

The race continued during the week and even entertained Christmas Day spectators. A New York Times reporter couldn’t understand the fascination. “Thousands who, despite the manifold discomforts to which they were subjected, found a mysterious fascination in the place that compelled them to linger hour after hour, gazing at the contestants and yelling themselves hoarse over the mediocre exhibition to which they were treated. The clouds of dust and tobacco smoke that were so dense that from one end of the building the other was invisible, made an atmosphere that was terrible to breathe, and proved very distressing to the pedestrians.”

Campana Crumbles

O’Leary declared a day later, “It was the poorest six days’ walk that I have ever made. I do not think that I shall walk much more. I shall retire from the track after the next match for the Astley Belt.” When asked about Campana he commented that he was a wonderful plucky man who was attended to poorly for the first two days of the walk. A doctor had too tightly wrapped his leg. “I have a great respect for him. He must have suffered intensely.” O’Leary was rumored to have received $12,000 from the race, valued at $333,000 today. Campana was on his feet the next day, recovering well, and hoped to compete in the next Astley Belt Race.

Campana’s Downfall

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Another article summed up the two disappointing six-day races held at Gilmore’s Garden, “When someone has made a great hit in a particular line of public entertainment, crowds of frauds and pretenders are sure to foist themselves on the public, in the hope of raking in heaps of shekels. Pedestrianism is no exception to this rule. Hughes and Campana – Frauds! Frauds! Frauds! Forced themselves before a long-suffering public.”

English papers called the O’Leary-Campana race “a wobble.” The New York press said the effort was “an absurd performance and was a disreputable fraud on the public.”

Six-Day Bicycle Race

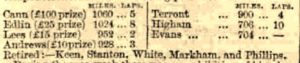

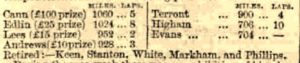

On November 18, 1878, the first six-day bicycle race in history was started at the Agricultural Hall in London for £100 pounds if the winning rider reached 1,000 miles. Among the competitors was the famous cyclist David Stanton (1844-1907), who was featured during the 1876 Grand Walking Tournament in Chicago (see episode 104).

The riders were restricted to ride 18 hours per day, when there were spectators present, and rode on a wooden track of boards, 7.5 laps to a mile. William Cann of Sheffield won the event on a high wheeler with a record 1,060 miles, 35 miles ahead of the next rider. The event was described as very exciting, with good attendance by spectators who witnessed some crashes. The track was defined poorly with a paint line and riders frequently cut corners. “We are left in a state of doubt as to the actual distance accomplished and thus the record is rendered practically worthless.”

Soon other six-day race firsts appeared in 1879 including swimming (75 miles), horse racing (557 miles), roller skating (644 miles), and even wheelbarrow pushing (310 miles).

This bicycle event was significant because some pedestrian historians believe these bicycle races eventually led to the lack of interest in the six-day running races and its downfall. However, that is an oversimplification of the eventual downfall of the six-day race. There were other far more impactful reasons for its demise that will be covered later. In the meantime, the glory days were still ahead.

Stay tuned for the truly amazing Third Astley Belt Race.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Michael O’Dwyer, “John Hughes”

- P. S. Marshall, “Napoleon Campana – Old Sport”

- “Six Day Cycle Race”

- The Bury and Norwich Post (England), Apr 2, 1878

- Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (England), Mar 26, 1878

- Manchester Evening News (England), Mar 27, Oct 12, 23, 1878

- The Sportsman (London, England), Apr 3, 1878

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 5, Nov 23, 1878

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Apr 27, 1878

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Apr 28, 1878

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Apr 29, 1878

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Mar 17, Oct 8, Nov 8, 1878

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 16, May 3, 23, Jul 25, Aug 11, Sep 29-30, 1878

- Sporting Life (London, England), Jul 24, Aug 31, 1878

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Aug 26, 1878, Jan 8, 1879

- Time Union (Brooklyn, New York), Sep 12, 1878

- Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), Sep 12, 1878

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Sep 12, Oct 1,6, Nov 17, 20. Dec 15, 30, 1878

- The Sun (New York, New York), Sep 30, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Sep 30, 1878

- Weekly Dispatch (London, England), Oct 13, 1878

- The Globe (London, England), Oct 28, 1878

- London Evening Standard (England), Oct 28, Nov 2-4, 1878

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Oct 30, 1878

- Penny Illustrated Paper (London, England), Nov 9, 1878

- The Yorkshire Herald (York, England), Nov 5-11, 1878

- Illustrated Police News (London, England), Nov 23, 1878

- The Referee (London, England), Nov 24, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 9, 29, 1878

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 24, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 27, 1878, Jan 26, 1879

- Lancaster Times (New York), Jan 23, 1879