Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:12 — 32.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

In early 1876 while Edward Payson Weston was taking on England in storm, embarrassing the British long-distance walkers and runners in the first six-day race in that country (see episode 99), the six-day race continued to be of growing interest in America, this time among women! Some in the press called these female wonders, “Pedestriennes.”

In early 1876 while Edward Payson Weston was taking on England in storm, embarrassing the British long-distance walkers and runners in the first six-day race in that country (see episode 99), the six-day race continued to be of growing interest in America, this time among women! Some in the press called these female wonders, “Pedestriennes.”

Was America truly ready to accept that idea that women could walk or run for days, for hundreds of miles? Obviously, there were strong cultural beliefs during the era that it was improper for women to participate in distance walking and running.

An editorial in the New York Times stated, “Today it is the walking match, soon the [women’s vote] will come.” It isn’t surprising that once the women started to compete that New York City considered passing an ordinance banning “all public exhibitions of female pedestrianism.”

| Please consider supporting ultrarunning history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Early Women Pedestrians

In 1876, female pedestrians were not entirely new. As early as 1844 in England, women started to attempt the Barclay Match, walking 1,000 miles in consecutive 1,000 hours, one mile each hour (see episode 18). Several British women were successful over the next thirty years. Often men wagering against their success would attempt to assault them to make them fail.

In America, in 1868, Anne Fitzgibbons, “Madame Moore,” a clog dancer from England, exported women pedestrianism to America. She began putting on 50-mile walking exhibitions in upstate New York, wearing “male attire” during her walks, for which she was arrested. She went on to be the first known woman to walk 100 miles in less than 24 hours.

There was speculation whether American women could be ultra-distance pedestrians. “American girls are generally poor walkers, and it will soon be a difficulty to find an American lady who can walk more than twenty minutes without complaining of fatigue. They pay too much attention to the shape and make of their boots for pedestrian performances.” A few isolated ultra-distances walks were performed by women during the early 1870s. In 1871, Lydia Nye walked 30 miles in eight hours over a rough, mountainous road near Bennington, Vermont. She received national attention in the newspapers.

In 1874 a woman created quite a stir who had walked all the way from Kansas City, to Sacramento, California “in search of a truant husband.” She wouldn’t take rides offered or ride the railroad because of a fear of trains. “That husband will be the biggest fool of the two if he ever lets her catch him.” Other women soon started to make walks of huge distances, getting their names in the news.

Time for a Women-only Six Day Race

Chicago, Illinois seemed to be the right place for women pedestrians to race for six days for the first time and gain initial acceptance. Daniel O’Leary had energized the city with his historic six-day victory over Edward Payson Weston late in 1875 (see episode 98). Two daring women took the stage to be the first women in history to compete in a six-day race: Bertha Von Hillern and Mary Marshall.

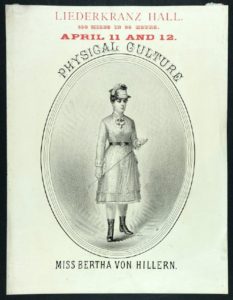

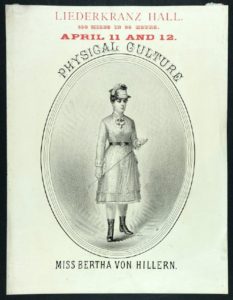

Bertha Von Hillern

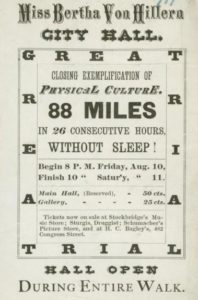

Von Hillern was not her true name. She used it for professional reasons, wanting to protect her family’s privacy. She walked in several matches in Berlin and other European cities during her teens to make some money for her parents. In October 1875, she emigrated to America at the age of 22, to start a new life, even though she spoke very little English. She made her way to the northside of Chicago Illinois where many German immigrants lived, where she continued walking and advocated athletic exercise for women.

The male press made this description of this unusual woman pedestrian, “Miss Von Hillern is 20 years of age, five feet and three inches in height, and weighs 110 pounds. Her hair is of light flaxen tint, her features somewhat irregular but pleasant, and her figure is trim.” She was actually 22 years old.

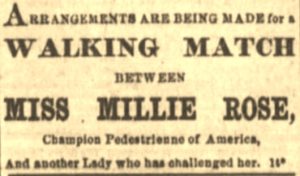

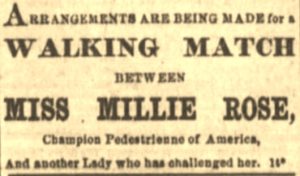

Von Hillern had interests in showing how far a woman could walk in six days. After Weston and O’Leary had raced in their six-day race, Von Hillern boldly published a challenge in a Chicago newspaper for a woman’s six-day race: “I Bertha Von Hillern, hereby announce my intention to exhibit my powers as a pedestrian in a contest in this city, for the championship of the world, with any woman of unblemished character.” Mary Marshall responded a month later.

Around 1870, the family moved to Chicago, where Thomas was a brass molder, working in foundries. Making ends meet was tough, and the family experienced bad financial difficulties. Tryphena became motivated to take up pedestrianism in 1875 to help with the family finances, and took up the stage name of Mary Marshall.

Preparations for the First Women’s Six-day Race in History

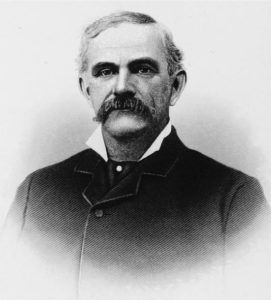

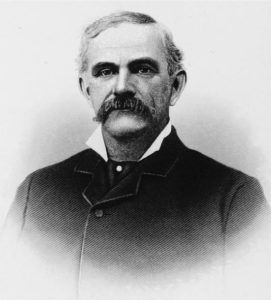

In January 1876, Marshall accepted Von Hillern’s challenge, and they asked Chicago’s famous pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary (1846-1933) to be the promoter and make the proper arrangements. Von Hillern wrote, “Your character as an honorable gentleman, together with your previous long experience in the same line, rendering you peculiarly fitted for the office. I trust that you will accept it for the honor of the craft which we both represent.” O’Leary eagerly accepted and helped the women to organize the event and to train.

The huge Exposition Building that O’Leary had previously competed in was preferred, but the owners asked for too much money. So, O’Leary contracted with the Second Regiment Armory building in Chicago, the same building that more than a century later would be used for the Oprah Winfrey Show. (In 1915 it was used as a massive morgue after the steamer Eastland overturned in the Chicago River, drowning about 850 of its passengers who were heading to a picnic. Many believed the building became haunted. Sadly in 2017 it was demolished to make room for the new corporate headquarters for McDonald’s.)

The interior of the building was prepared with an oval sawdust track of ten laps to a mile and could seat about 3,000 spectators. Instead of a full six days, the race was scheduled for five and a half days, probably because of scheduling conflicts. The prize for the winner would be $500.

The Start

In contrast, “The German is dressed in style not less showy than her opponent, having a red, black, and yellow short skirt with trimmings, a black velvet basque with yellow and red shield on the breast, and plenty of other ornamentations, especially light-yellow kids. She is also blonde though not so light as Mrs. Marshall. She is some 4 inches shorter.”

O’Leary shouted ‘Go,” and the pioneer women pedestrians were off. Von Hillern, had a shorter stride and walked more erect with her head thrown far back. After stopping on the first lap with a broken shoelace, Marshall pushed forward with more speed and opened up good lead, taking frequent rests as Von Hillern plodded along at a steady pace without stopping.

At about the 20th mile, a better’s voice was heard to yell out offering a 2-1 bet on “American Girl.” A small man came down in front and signified that he would accept the wager, expressing his confidence in “the Flying Duchess” to win. After 12 hours, the two retired for the night. Marshall had reached 33 miles and Von Hillern, 31 miles.

Day Two

Rose, with her husband and another man, stormed into the newspaper’s editor’s office, demanding to know who wrote the offensive article. The editor, George C. Harding (1829-1881) who himself was a rough character, admitted to being the author of the piece. Rose demanded a retraction but was told to leave. “Then the little Rose of Paradise, without any further words, unsheathed her trusty cowhide from the folds of her shawl and struck the editor several blows across the face. The editor seized an umbrella and tried to beat off the irate female, with more or less success until the woman stumbled and fell back. Just then, the husband drew his pistol, but before any shooting had taken place, the printers had rallied in force and the disturbers of the peace were landed on the sidewalk in a twinkling.” Harding with a cut under an eye, pressed charges and an arrest warrant was issued which apparently stopped the 500-mile attempt. (Four years later Harding went on trial for attempting to shoot an editor of a rival paper, taking issue with something that was printed. He died young at the age of 51 in 1881 from blood poisoning after his foot was accidently cut.)

By noon on day two, after more than 24 hours, the smiles faded from Von Hillern’s and Marshall’s faces like “a free lunch before a posse of hungry beer-guzzlers.” They had started the race in new shoes, and the leather feasted on their heels causing blisters to set in. Their walking was stopped at about 9 p.m. for the night because of medical concerns. Dr. William P. Dunne (1947-1882) Chicago City Physician, who had worked with O’Leary’s walks, took care of them, and dressed their wounds. The mileage score was tied with both at 74 miles.

Day Three

As for the main show, by noon, Marshall again had a lead of about two miles. “Their spirits and courage are unabated, and the efforts of the one to defeat the other go far in making the interest taken in the undertaking the more intense.”

Rose’s 50-mile attempt failed. By 10 p.m. she grew pale and began to stumble. She quit because of illness after about eleven and a half hours with only 38 miles, announcing that she would do another walk the following day. “She had the sympathy of all who witnessed her very wonderful powers.”

Day Four

Day Five

Von Hillern started that morning at the same time. Her feet were in great shape with no blisters. She would generally walk in silence, only talking to her German-speaking handlers, and still when it was only absolutely necessary. “Aside from a paleness, she looked as well as when she first started, her dress being trim and neat, and her hair was combed as carefully as though she was prepared for the stage. Her hands were covered with kid gloves, which as soon as soiled, were replaced by others that were new.”

It was reported “Mrs. Marshall is pretty well used up and is sure to lose a few toenails, owing to her having worn tight shoes for hours. O’Leary’s shoemaker was telegraphed for at noon, and he brought with him several pairs of walking shoes into one of which she jumped. Feeling thus relieved, she made some fine walking during the afternoon and evening, and asserts that although behind her antagonist, she will be able to catch up with her.” A male reporter commented on “her large lustrous eyes” that focused on the ground with a look of pain and weariness. She had to leave the track often, while Von Hillern pushed on steadily and increased a lead.

Von Hillern was now the favorite, “possessed with greater powers of endurance, and is sure to be the winner of the race She is of metal more tough than her opponent and exhibits but few symptoms of weariness. Mrs. Marshall’s strength, however well supported by her will, is wholly inadequate to cope with the experience and training of Miss Von Hillern.” When they retired for the night, Von Hillern was leading with 192 miles to 186.

The Chicago press thought Marshall was making a big mistake continuing and wrote about her unfairly compared to men who had also been worn out on their fifth day of walking. “It is confidently hoped, however, that she never again be so foolish as to represent herself so shamefully, and it will be a pleasant surprise if she is ever able to resume her gaining of a livelihood by canvassing for the sale of books.”

Day Six

“As the night wore on, the excitement gained a fearful pitch. So great was the jam about the scorer’s stand that it was necessary for him stop placing the figures on the board, it being as much as he could to keep a correct tally on the book.” Controversy arose when spectators and Von Hillern believed that the judges had shorted her lap count. The judges checked things out and posted an official score showing Marshall in the lead. Some historians speculate that judges felt pressured by the larger group of pro-Marshall wagers to doctor the score, but there is no firm evidence to hold up that narrative.

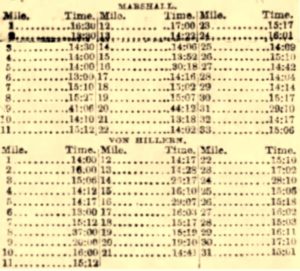

The race concluded at 10:40 p.m. after five and a half days (132 hours). Marshall won, reached 233.9 miles to Von Hillerns’ 231.5 miles. O’Leary, with his reputation, defended the results.

Both women were completely exhausted. Marshall had to be carried to her room. She was in such a terrible state that she was given opiates to quiet her down. Some thought that she was going insane because she wasn’t able to speak. It wasn’t until the next morning that she started resting better. Von Hillern came away in much better condition and was able to walk fine the next day. A week later, Marshall had almost entirely recovered and started to make public appearances giving walking exhibitions.

Reaction Around the Country

The male attitudes frowning on the activity were obvious. “If there were a husband at the end of a 300-mile route, to be awarded to the girl who could get to him the soonest, the competition might be profitable, provided the man was worth walking after.”

But The Chicago Daily News knew that Marshall accomplished something huge. “Marshall’s fame, if she survives the fearful ordeal, is set for life.” Other women athletes were very impressed and wanted to also achieve glory and riches. A woman’s six-day frenzy was sparked as other women wanted to get into the action. This will be covered in the next episode.

News of the race made it to faraway England where Weston was competing. “The original intention was to walk 300 miles for a purse of 300 dollars, but neither was able to make the distance on account of exhaustion.”

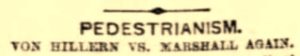

Challenge for a Rematch

Von Hillern believed that Marshall won unfairly because she walked laps on the last days without shoes, in stocking feet. She said that was against governing rules for pedestrian contests, a silly charge because these races were so new, without such small details specified. Von Hillern also complained about the foul air from the dense crowd and “vile tobacco smoke” that caused her to faint near the end of the race. Others contended that somehow Marshall must have been doped on the last day, coming back from being nearly dead to win.

“The referee in the match, Mr. O’Leary, declared in favor of Miss Marshall, a decision which gave general dissatisfaction, as the friends of Miss Von Hillern were satisfied that they had not been fairly dealt with. The affair created considerable discussion, each party thinking that with unbiased judges she was able to defeat the other.”

Rematch in the West Side Rink

Large audiences came out to the event. Several local pedestrians, both men and women, were allowed to join in for a while. At the end of day two, Marshall was at 141 miles with a two-mile lead.

“Miss Von Hillern continues in first-class condition and is as fresh as when she started. Her appetite is good, and she eats three sound meals a day. Mrs. Marshall seems not so fresh as the German girl, but has so far kept up well, and is confident that she can make a good showing. Miss Verner is still walking but is hopelessly behind and walks very lame.”

In the end, Marshall won again, this time by about six miles, with a new world record of at least 300 miles.

A few days later, local citizens living near the West Side Rink complained loudly that the building was a terrible fire-hazard for the neighborhood and the historic ultrarunning venue was soon condemned and torn down.

Von Hillern still wasn’t satisfied and never again competed in Chicago. Like Weston and O’Leary, the two women became the most famous female pedestrians in the world and eight months another much-anticipated rematch would be held.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Chip Curtis, great-great grandson of Mary Marshall, Family History notes

- Harry Hall, The Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars

- Albans Daily Messenger (Vermont), Jul 24, 1871

- The Placer Herald (Rocklin, California), Jun 13, 1874

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Jan 29, 1876

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Dec 19, 21, 1875, Jan 30-Feb 5, 11, 13, 24, Mar 12, 15, 25, 1876

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 3-7, Mar 15, 1876

- The Globe (London, England), Feb 21, 1876

- Burlington Weekly Hawk (Iowa), Dec 16, 1875

- The St. Albans Advertiser (Vermont), Dec 28, 1875

- Gallipolis Journal (Ohio), Feb 24, 1876

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Feb 4, 1876

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Feb 4, 1876

- The Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas), Feb 10, 1876

- The Hillsdale Standard (Michigan), Mar 28, 1876

- Belfast News-Letter (Northern Ireland), Jan 13, 1877