Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:45 — 33.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

By the end of 1878, at least 41 six-day races had been held in America and Great Britain since P.T. Barnum started it all with the first race in 1875. Daniel O’Leary of Chicago was still the undefeated world champion with ten six-day race wins. He was a very wealthy man, winning nearly one million dollars in today’s value during 1878.

By the end of 1878, at least 41 six-day races had been held in America and Great Britain since P.T. Barnum started it all with the first race in 1875. Daniel O’Leary of Chicago was still the undefeated world champion with ten six-day race wins. He was a very wealthy man, winning nearly one million dollars in today’s value during 1878.

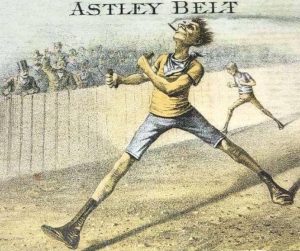

All the racing was taking a toll on O’Leary, and he had frequent thoughts about retiring. However, he still had obligations as the holder of the Astley Belt and the title of Champion of the World. If he could defend the Astley Belt one more time, three wins in a row, by rule he could keep the belt. A Third Astley Belt Race was in the early planning to be held sometime during the summer of 1879. In January he went to Arkansas to rest at the famous hot springs with its six bathhouses and 24 hotels.

Little did he know that the Third Astley Belt Race would be one of the most impactful spectator events in New York City 19th century history witnessed by more than 80,000 people. It impacted ten of thousands of workers’ productivity for a week and even distracted brokers on Wall Street away from their ticker tapes. The major New York City newspapers included more than a full page of details every day that revealed the most comprehensive details ever of a 19th century six-day race. Because of its historic importance, this race will be presented in two articles/episodes.

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Astley Backs a Potential British Champion

Sir John Astley wanted to make sure a Brit would next win the belt. After putting on an English Championship in late October 1878, he identified the best British candidate that he thought could contend with O’Leary and bring the Astley Belt back to England. His man was Charles Rowell, who had recently placed third in Astley’s English Championship Six-Day race with 470 miles. Astley formally issued a challenge to O’Leary on behalf of Rowell.

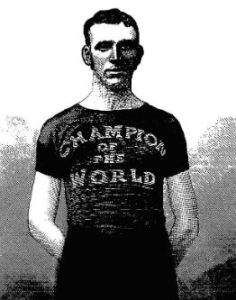

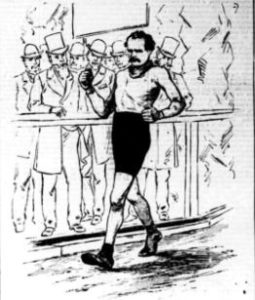

Charles Rowell

Charles Rowell (1852-1909), age 26, was born in Chesterton, Cambridge, England, and was fond of sports athletics in his childhood. He had gained some fame as a rower at Cambridge and was regarded as one of Britain’s top emerging athletes. He started his running career in 1872, winning some races. In 1874 he won a 19-mile race in 1:57:45 and later covered 32 miles in four hours. He was no doubt very fast.

Charles Rowell (1852-1909), age 26, was born in Chesterton, Cambridge, England, and was fond of sports athletics in his childhood. He had gained some fame as a rower at Cambridge and was regarded as one of Britain’s top emerging athletes. He started his running career in 1872, winning some races. In 1874 he won a 19-mile race in 1:57:45 and later covered 32 miles in four hours. He was no doubt very fast.

When Edward Payson Weston first came to England in 1876, Rowell raced against him in a 275-mile track race in the Agricultural Hall in London. He mostly played the role as a pacer and completed 175 miles to Weston’s 275 miles.

Astley charged Rowell to get himself fit and promised to pay the expenses for him to travel to America for the Third Astley Belt Race. After a few weeks of training, Astley invited Rowell to his estate and observed his running abilities. “I was satisfied that he was good enough to send over to try and bring back the champion belt to England.” He provided £250 for his expenses. Prior to leaving England, it was rumored that he had covered a world record 539 miles in a private six-day trial, but Rowell would not confirm or deny it.

Third Astley Belt Scheduled

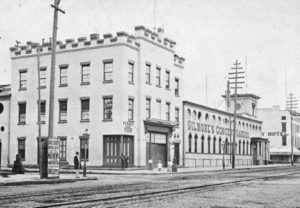

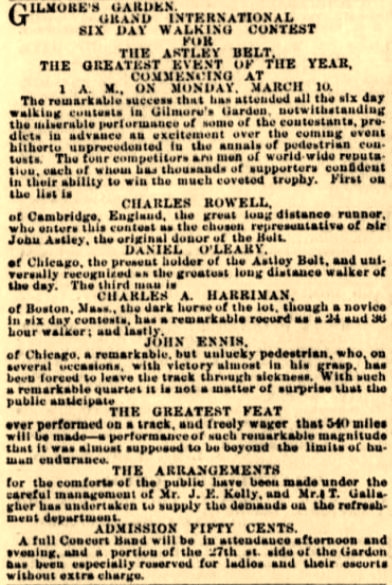

On November 7, 1878, John Ennis of Chicago, was the first runner to properly apply to London’s Sporting Life (the stakeholder) to challenge for the Astley Belt. Charles A. Harriman of Boston was the next, followed by Charles Rowell on December 1, 1878. By the end of January 1879, O’Leary accepted the challenges and started planning for a June race. But within a few days, John Astley, the founder of the Astley Belt series, decided that the next Astley Belt Challenge would be held in March 1879 at New York City in Gilmore’s Garden, soon to be renamed Madison Square Garden. This near-term race date came as a huge surprise to Americans O’Leary, Harriman, and Ennis.

On November 7, 1878, John Ennis of Chicago, was the first runner to properly apply to London’s Sporting Life (the stakeholder) to challenge for the Astley Belt. Charles A. Harriman of Boston was the next, followed by Charles Rowell on December 1, 1878. By the end of January 1879, O’Leary accepted the challenges and started planning for a June race. But within a few days, John Astley, the founder of the Astley Belt series, decided that the next Astley Belt Challenge would be held in March 1879 at New York City in Gilmore’s Garden, soon to be renamed Madison Square Garden. This near-term race date came as a huge surprise to Americans O’Leary, Harriman, and Ennis.

Clearly Astley believed that Rowell was ready to be sent to America and didn’t want to wait until June. O’Leary’s camp stated that Astley wanted to hurry up the match because he believed O’Leary was out of shape after his match with Campana a month earlier that really trashed his feet and overall health (see episode 107). But the Chicago newspaper countered, “If this is the case, they are much mistaken. O’Leary is all right.”

O’Leary, who was still at the hot springs in Arkansas, thought the decision was unfair and arbitrary, but he knew he couldn’t fight it. He wasn’t going to lose the belt over a scheduling battle. With the surprising announcement, it also gave other Americans, such as George Guyon, only five days to send their entrance fee to London. No additional runners entered in time. Astley was a shrewd, determined character. O’Leary gave in and said, “I am ready to walk at two days’ notice.”

Rowell Arrives in America

In mid-February, Rowell boarded the steamship Parthia for New York City with a sendoff by Astley who made sure the captain of the ship gave him great accommodations.

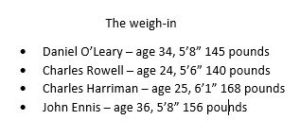

He arrived on February 28, 1879, and O’Leary kindly met him at the dock to welcome him to America. Rowell was pleased that O’Leary greeted him. “As they stood side by side on the deck of the steamer, the two men presented a rather striking contrast in point of build and stature. O’Leary is about three inches taller than Rowell, but much slightly in build, looking quite a delicate man compared with the thick set, compact form of the Englishman. O’Leary may be classed as a fair heel and toe walker, though he occasionally runs a few laps, while Rowell is a runner, and will cover at least four-fifths of his journey in a jog trot.”

He arrived on February 28, 1879, and O’Leary kindly met him at the dock to welcome him to America. Rowell was pleased that O’Leary greeted him. “As they stood side by side on the deck of the steamer, the two men presented a rather striking contrast in point of build and stature. O’Leary is about three inches taller than Rowell, but much slightly in build, looking quite a delicate man compared with the thick set, compact form of the Englishman. O’Leary may be classed as a fair heel and toe walker, though he occasionally runs a few laps, while Rowell is a runner, and will cover at least four-fifths of his journey in a jog trot.”

Rowell walked to Gilmore’s Garden to look at the venue of the race and then walked downtown to the St. James Hotel to have a runners’ meeting with O’Leary, Harriman, and Ennis. Ennis had recently arrived from Chicago after a terrible road trip was delayed enroute for two days because of heavy snow. They negotiated the division of the resulting gate money and set firmly the start date for the race to be March 10, 1879. Good feelings were felt. Ennis joked that Harriman, who was over six feet tall, was too tall to walk against the three other shorter men and suggested that he should be cut down to regulation length.

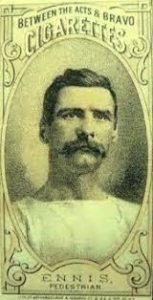

John Ennis

John T. Ennis (1842-1929), age 36, was a carpenter from Chicago. He was born in Longford, Ireland, emigrated to America while young and served in the Civil War for Illinois. He had been competing in walking since 1868. He had beaten O’Leary in a handicapped race, early in October 1875, walking 90-miles before O’Leary could reach 100-miles. He also was a very talented endurance ice-skater. In 1876, he skated for 150 miles in 18:43.

John T. Ennis (1842-1929), age 36, was a carpenter from Chicago. He was born in Longford, Ireland, emigrated to America while young and served in the Civil War for Illinois. He had been competing in walking since 1868. He had beaten O’Leary in a handicapped race, early in October 1875, walking 90-miles before O’Leary could reach 100-miles. He also was a very talented endurance ice-skater. In 1876, he skated for 150 miles in 18:43.

Ennis was a veteran of several six-day races, but he usually came up short due to stomach problems. Many in Chicago had turned against him. “Is it not about time that this man should end his nonsensical talk? He has made more failures than any known pedestrian in this country.” His pre-race bio included: “John Ennis of Chicago, a remarkable, but unlucky pedestrian, who on several occasions, with victory almost in his grasp, has been forced to leave the track through sickness.”

In 1878, Ennis finally started to taste success. He won a six-day race in Buffalo, New York, but only reached 347 miles. Then he finally had good success walking six days in September 1878, again at Buffalo. He won with 422 miles. The next month he went to England and raced against Rowell and others in the English Astley Belt Race where he finished 5th with 410 miles.

Charles Harriman

Charles A. Harriman (1853-), age 25, was a shoemaker, originally from Maine but living in Haverhill, Massachusetts. He began his running career in 1868 in short sprinting races. His ultradistance experience was recent, but impressive, breaking the existing walking 100-mile world record with a time of 18:48:40. With no six-day experience, he entered the next Astley Belt Race and was accepted.

Harriman had trained hard for the race. His pre-race bio included: “Charles A. Harriman, the dark horse of the lot, though a novice in six-day contests, has a remarkable record as a 24- and 36-hour walker.” He predicted that he would cover 125 miles during the first 24 hours.

Runners Preparations for the Race

A week before the race Rowell and Ennis trained together in Central Park. Harriman walked on the city streets for several miles and spent a bit too much time flirting with the beautiful wife of the St. James Hotel steward, who he would run away with in the coming months, causing a big scandal. O’Leary took it easy, made no predictions, and went to Gilmore’s Garden to watch Rowell run.

New York was curious about the Englishman. “Rowell is the smallest man of the four candidates and now weighs about 140 pound in costume. His style of progression is a trot, yet he moves along with little apparent exertion. Very solidly built, Rowell seems capable of bearing much fatigue, and judging from his conversation, he is hopeful of winning.” Rowell said, “I am not a walker. I know how to run, but I am a poor walker.”

Gilmore’s Gardens Prepared

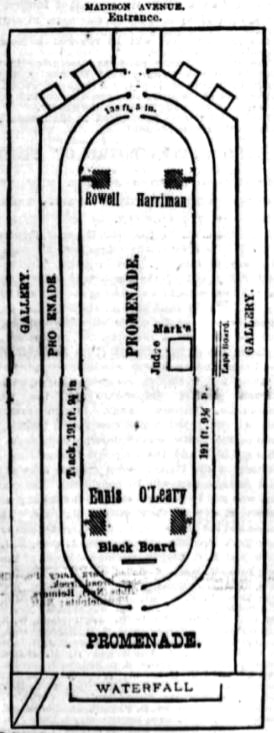

At Gilmore’s Gardens, the 8-foot-wide track, eight laps to the mile, was improved to eliminate the clouds of dust that hindered the earlier O’Leary-Campana race. It was composed of compacted sawdust on clay and rolled for hours.

At Gilmore’s Gardens, the 8-foot-wide track, eight laps to the mile, was improved to eliminate the clouds of dust that hindered the earlier O’Leary-Campana race. It was composed of compacted sawdust on clay and rolled for hours.

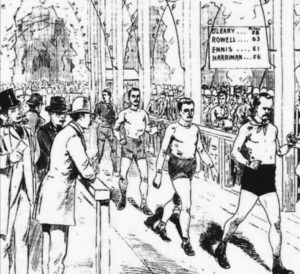

Careful attention was paid to make sure the spectators had good accommodations. A 12-foot-wide platform was constructed outside of the track with a railing for spectators to view the runners closely. “The space for scorers and members of the press was ample, and well-protected from unwarrantable intrusion by a high picket fence.”

Careful attention was paid to make sure the spectators had good accommodations. A 12-foot-wide platform was constructed outside of the track with a railing for spectators to view the runners closely. “The space for scorers and members of the press was ample, and well-protected from unwarrantable intrusion by a high picket fence.”

Police officers would be stationed to prevent spectators from interrupting the competition. A huge blackboard was placed in the center of the building for every mile to be promptly posted. A box near the Madison Avenue entrance was designated to be the telegraph office and wires were run to the Western Union Building. Messages would be sent to England directly from the track. Fires from seventeen furnaces would warm the building. Huts/cottages were provided for each man and their crews. They were ten-by-eleven feet, and each was furnished with gas stoves, comfortable beds, and plenty of cooking utensils.

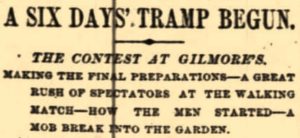

The Wild Start

The Third Astley Belt Race, held on March 10, 1879, was billed as, “The greatest pedestrian match that has ever been contested in this country.” It perhaps had the most bizarre start in the history of ultrarunning. Three hours before the 1 a.m. start, hundreds of interested spectators lined up five deep for a block long on Madison Avenue, anxious to buy tickets. The ticket sellers worked furiously, and hundreds of people pressed into the building without paying. “Such a scene has not been witnessed previously at a walking match. When the doors opened, there was a rush by the eager throng.” Liquor was sold at a bar and the bartenders started doing a very lively business.

The Third Astley Belt Race, held on March 10, 1879, was billed as, “The greatest pedestrian match that has ever been contested in this country.” It perhaps had the most bizarre start in the history of ultrarunning. Three hours before the 1 a.m. start, hundreds of interested spectators lined up five deep for a block long on Madison Avenue, anxious to buy tickets. The ticket sellers worked furiously, and hundreds of people pressed into the building without paying. “Such a scene has not been witnessed previously at a walking match. When the doors opened, there was a rush by the eager throng.” Liquor was sold at a bar and the bartenders started doing a very lively business.

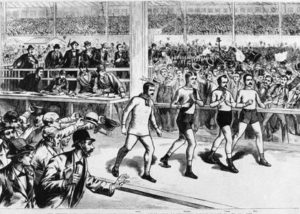

As thousands of people were pouring into Gilmore’s Garden, the contestants arrived at midnight, greeted by 4,000 people, and shut themselves in their little huts, away from the confusion, to prepare. With a half hour to go, the crowd was surging back and forth and there was still a mass of people outside wanting to get in. The police did their best to hold off a rush through the door. The Astley Belt was put on display at the judges stand. The runners came out and rules were read. The runners could reverse direction at a mile mark and the runner going counterclockwise had the inside right-of-way. “Meanwhile the great crowd was as noisy and unruly as possible and the brass band in attendance could hardly drown the noise made by excited betters.”

Off They Go

A few minutes before the start at 1 a.m., with the building full of about 10,000 people, the police closed the outer doors, greatly disappointing those who were shut out on the street. “This caused a howl of disappointment and rage.” The four contenders for the Belt lined up at the start line. Thousands wanted to watch the start and stood on tables and chairs and even one another’s shoulders.

A few minutes before the start at 1 a.m., with the building full of about 10,000 people, the police closed the outer doors, greatly disappointing those who were shut out on the street. “This caused a howl of disappointment and rage.” The four contenders for the Belt lined up at the start line. Thousands wanted to watch the start and stood on tables and chairs and even one another’s shoulders.

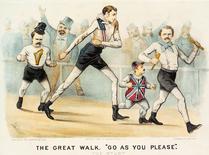

William B. Curtis (1837-1900), who founded the athletic clubs in New York and Chicago, was the starter and shouted the word “Go”. O’Leary led the group in a fast walk, but before the lap was complete, Rowell broke out into a trot. O’Leary soon also started into a trot and soon all four were running, causing a frenzy among the spectators.

William B. Curtis (1837-1900), who founded the athletic clubs in New York and Chicago, was the starter and shouted the word “Go”. O’Leary led the group in a fast walk, but before the lap was complete, Rowell broke out into a trot. O’Leary soon also started into a trot and soon all four were running, causing a frenzy among the spectators.

Then it happened! When the first mile was announced on the blackboard with a time of 9:25, the cheering was deafening. Those who were left outside the building, heard the roar. The outside crowd turned into an angry mob and rushed for the entrance, overwhelming the two policemen out there, broke down the door off its hinges and pushed into the building.

A dozen policemen inside rushed to meet the mob, including police captain Alexander “Clubber” Williams (1839-1917) who was known for his brutality. “Then occurred one of the liveliest scrimmages seen in New York for a long time. The police used their clubs freely, and the blows fell thick and fast at random. This harsh usage was effectual, and the mob was driven clear of the building. The sound of the heavy blows rained upon the defenseless heads and bodies of the unfortunates who happened to be in the front ranks was sickening.”

A dozen policemen inside rushed to meet the mob, including police captain Alexander “Clubber” Williams (1839-1917) who was known for his brutality. “Then occurred one of the liveliest scrimmages seen in New York for a long time. The police used their clubs freely, and the blows fell thick and fast at random. This harsh usage was effectual, and the mob was driven clear of the building. The sound of the heavy blows rained upon the defenseless heads and bodies of the unfortunates who happened to be in the front ranks was sickening.”

The riot that took place was not only because the crowd was denied entry, but also because of the police brutality that injured seventy people and sent them to the hospital. Rocks were thrown at the windows of the building, breaking at least one, and some climbed onto the roof. Police patrol lines were eventually established so that nobody could approach within a block of the Garden. Those inside the building didn’t dare to venture out among the angry thousands. After two hours the outside crowd finally dispersed.

The riot that took place was not only because the crowd was denied entry, but also because of the police brutality that injured seventy people and sent them to the hospital. Rocks were thrown at the windows of the building, breaking at least one, and some climbed onto the roof. Police patrol lines were eventually established so that nobody could approach within a block of the Garden. Those inside the building didn’t dare to venture out among the angry thousands. After two hours the outside crowd finally dispersed.

Meanwhile, Rowell continued to run, leading the small pack, completing the first eight miles in 1:10, with O’Leary about a mile behind. “O’Leary walks with his usual graceful stride and is loudly applauded. He outruns Rowell whenever he wants to.” At times the runners were in single file trotting. “At such times the people in the inner circle would rush from side to side to get a better view of the men, the tramping of their feet sounding like a squadron of cavalry.” Both O’Leary and Ennis became sick during the morning and needed to take frequent rests, falling behind.

Meanwhile, Rowell continued to run, leading the small pack, completing the first eight miles in 1:10, with O’Leary about a mile behind. “O’Leary walks with his usual graceful stride and is loudly applauded. He outruns Rowell whenever he wants to.” At times the runners were in single file trotting. “At such times the people in the inner circle would rush from side to side to get a better view of the men, the tramping of their feet sounding like a squadron of cavalry.” Both O’Leary and Ennis became sick during the morning and needed to take frequent rests, falling behind.

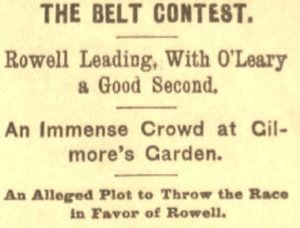

Rowell was the first to reach 100 miles, in 19:34:45, with O’Leary 13 miles behind still plagued by a sour stomach. When they were on the track at the same time, Rowell would tuck in behind O’Leary on the laps and never let O’Leary unlap himself. When O’Leary would break into a trot, Rowell would do the same.

Rowell was the first to reach 100 miles, in 19:34:45, with O’Leary 13 miles behind still plagued by a sour stomach. When they were on the track at the same time, Rowell would tuck in behind O’Leary on the laps and never let O’Leary unlap himself. When O’Leary would break into a trot, Rowell would do the same.

A strange rumor was circulating that one of O’Leary’s trainers, the pedestrian William Edgar Harding (1848-), editor of the National Police Gazette, was plotting to poison O’Leary on day four. O’Leary dismissed the charge as ridiculous and kept Harding on this team.

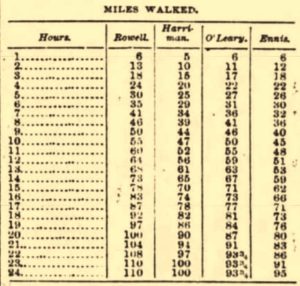

At the end of day one, the score was Rowell 110 miles, Harriman 100, Ennis 95, and O’Leary 93. Before the race, O’Leary was the favorite among betters, but now Rowell was the favorite.

Day Two

At 2:00 a.m., on day two, O’Leary was the only man on the track and was cheered by about 1,000 people who were still there. At 4:40 a.m., Rowell resumed running.

At 2:00 a.m., on day two, O’Leary was the only man on the track and was cheered by about 1,000 people who were still there. At 4:40 a.m., Rowell resumed running.

The race captured the imagination of New York City. Bulletins were displayed and kept updated out in the streets that attracted crowds of eager news seekers. “Such general interest in a match of this kind has never been excited in this or any other city. It is the one theme of town talk, and the throngs that haunt the scene of the contest at all hours of the day and night are unprecedented.”

The city streets were truly transformed on the blocks that housed newspaper buildings. “Groups of patient and persistent onlookers remained for an hour at a time to see the next announcement placed on the board. As each even hour approached, streams of people flowed in the direction of the Herald office. ‘What’s the news? Who’s ahead?” Stage drivers would even slow down their carriages as they passed to get a little news.

The city streets were truly transformed on the blocks that housed newspaper buildings. “Groups of patient and persistent onlookers remained for an hour at a time to see the next announcement placed on the board. As each even hour approached, streams of people flowed in the direction of the Herald office. ‘What’s the news? Who’s ahead?” Stage drivers would even slow down their carriages as they passed to get a little news.

Boys who could not afford a ticket would use their jackknives to cut holes through a wall panel of Gilmore’s Garden to get a peek at the action inside.

Rowell started to be referred to as the “little feller,” and did many long runs. His handlers spent most of their time “concocting mysterious drinks and messes over the small gas stove that occupies one corner of the apartment.” They were very secretive and would not answer questions about how Rowell was doing.

The tall Harriman kept up a tremendous pace with a great swinging stride at “the untiring regularity of a machine.” He started to receive the nickname “steamboat.” Ennis was called, “Honest John” by his friends. While on the track, he would do a lot of running.

The band was having a wonderful time, sometimes playing tunes that would annoy O’Leary. Spectators would beat time with their feet and whistle or hum in unison. “Everybody was good natured and cherry. A solid buzz kept coming up all over the hall. Waiters in spotless white aprons would flit about here and there, handing foaming beer mugs to dainty, elegantly clad ladies in the reserved boxes. The great overhanging balcony was alive with hearty, smoking, noisy men.” Bookmen canvassed the crowd with their little red books taking bets.

The band was having a wonderful time, sometimes playing tunes that would annoy O’Leary. Spectators would beat time with their feet and whistle or hum in unison. “Everybody was good natured and cherry. A solid buzz kept coming up all over the hall. Waiters in spotless white aprons would flit about here and there, handing foaming beer mugs to dainty, elegantly clad ladies in the reserved boxes. The great overhanging balcony was alive with hearty, smoking, noisy men.” Bookmen canvassed the crowd with their little red books taking bets.

An enormous bar counter, 400 feet long, took up the space under the gallery. It was the equivalent of 20-30 bars, each with a bartender. “Men five to ten deep pushed, swearing, smoked, hustled and bustled and shouted for their favorite beverage. They drank beer by the hundred kegs, whiskey by the barrel and gin by the gallon. Money flowed like beer. Everybody drank pretty much all the time.”

An enormous bar counter, 400 feet long, took up the space under the gallery. It was the equivalent of 20-30 bars, each with a bartender. “Men five to ten deep pushed, swearing, smoked, hustled and bustled and shouted for their favorite beverage. They drank beer by the hundred kegs, whiskey by the barrel and gin by the gallon. Money flowed like beer. Everybody drank pretty much all the time.”

Meanwhile, everything on the track was business. Ennis looked the freshest. Harriman looked worn out and it was rumored that Rowell had a leg “getting out of order” with a calf strain. It seemed clear that O’Leary had not fully recovered from his last six-day walk two months earlier. He was said to look stale, not walking with any of his old vim, holding his piston rods almost down to his knees. Harriman and Enis encouraged him along. The crowd kept yelling, “Keep it up, Dan!”

Meanwhile, everything on the track was business. Ennis looked the freshest. Harriman looked worn out and it was rumored that Rowell had a leg “getting out of order” with a calf strain. It seemed clear that O’Leary had not fully recovered from his last six-day walk two months earlier. He was said to look stale, not walking with any of his old vim, holding his piston rods almost down to his knees. Harriman and Enis encouraged him along. The crowd kept yelling, “Keep it up, Dan!”

As midnight approached, a gang of gate crashers used a beam of wood as a battering ram to break down a door to get in the building. Police eventually rounded them up, arrested them, took them out of the building, beat them, and then let them go.

At the end of day, 48 hours, the score was Rowell 197 miles, Harriman 186, Ennis 173, and O’Leary 164.

Day Three

The crowd thinned out during the early hours of day three. A few made beds for themselves from seats. “The spectators wore a subdued look, some having their eyes closed in slumber and others yawning at frequent intervals.” Dawn arrived and the tired runners were back on the track.

In the afternoon, Rowell tried to use his shadowing strategy on Harriman, running close on his heels. Harriman said, “It didn’t bother me. I heard the Englishman puffing pretty hard, that is all.” The crowd didn’t like watching these dogging antics from Rowell and yelled at him, “There’s Harriman’s bull pup, come here little doggy.” They encouraged Harriman to get a leach for his new dog. Then to Rowell, “Why don’t you jump up on his shoulders? Get him to tote you around little boy!”

O’Leary Breaks Down

But the main story of the day on the track was O’Leary’s demise. He reached his 200th mile, but his pace was terribly slow with “some feeble spurts, which were like the efforts of a drowning man to surmount the waves.” It was obvious that he had broken down as he could hardly walk a single yard without swerving back and forth. The crowd gave him silent respect. His attendants wore sad faces. His backer admitted that O’Leary wasn’t in good shape for the race, still not recovered from his last one.

But the main story of the day on the track was O’Leary’s demise. He reached his 200th mile, but his pace was terribly slow with “some feeble spurts, which were like the efforts of a drowning man to surmount the waves.” It was obvious that he had broken down as he could hardly walk a single yard without swerving back and forth. The crowd gave him silent respect. His attendants wore sad faces. His backer admitted that O’Leary wasn’t in good shape for the race, still not recovered from his last one.

He still tried to plod along courageously, but during mile 216, he had to stop three times. He was about 35 miles behind Rowell. O’Leary was seized with violent pains and strange sensations that made some believe that a trainer had poisoned him. The crowd was hopeful that he would return and in unison gave three cheers for O’Leary.

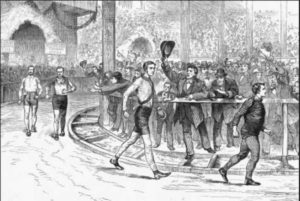

The doctor determined that his health had declined beyond the ability to continue. O’Leary eventually came out, walked to the judges stand, and said, “Gentleman, I have finished.” He would be giving up the Astley Belt. An evening news story was published, and newsboys went to every part of the city, theaters, hotels, squares, and secluded streets spreading the sad news about the fallen champion.

The doctor determined that his health had declined beyond the ability to continue. O’Leary eventually came out, walked to the judges stand, and said, “Gentleman, I have finished.” He would be giving up the Astley Belt. An evening news story was published, and newsboys went to every part of the city, theaters, hotels, squares, and secluded streets spreading the sad news about the fallen champion.

Later, a rumor spread all over the city that O’Leary was dead. Police Captain “Clubber” Williams confirmed the false report stating that the champion had died at the Metropolitan Hotel shortly after he had been brought there. Then it was reported that O’Leary had died from being poisoned and that a man had been arrested. The poor hotel clerks were deluged with hundreds of inquiries, but they denied that O’Leary had even been staying there. The city coroner even dropped by the hotel in search of the body. O’Leary was eventually found at St. James Hotel and the coroner proclaimed, “O’Leary never looked better in his life. There is nothing the matter with him.” Well, then why did O’Leary leave the track? The coroner replied, “Because he was tired and couldn’t go any further.”

Later, a rumor spread all over the city that O’Leary was dead. Police Captain “Clubber” Williams confirmed the false report stating that the champion had died at the Metropolitan Hotel shortly after he had been brought there. Then it was reported that O’Leary had died from being poisoned and that a man had been arrested. The poor hotel clerks were deluged with hundreds of inquiries, but they denied that O’Leary had even been staying there. The city coroner even dropped by the hotel in search of the body. O’Leary was eventually found at St. James Hotel and the coroner proclaimed, “O’Leary never looked better in his life. There is nothing the matter with him.” Well, then why did O’Leary leave the track? The coroner replied, “Because he was tired and couldn’t go any further.”

O’Leary’s doctor was asked why O’Leary broke down so soon. He blamed it on his trip to the Hot Springs which softened up his feet. “Then the atmosphere in this Garden was simply rank poison, as bad as arsenic. At every breath he got a mouthful of dust, smoke, and stale air.”

O’Leary would not win the Astley Belt for the third time in a row and thus could not claim it permanently. It would have a new steward.

At 4 p.m. on day three, the score was Rowell 250 miles, Harriman 238, Ennis 223, and O’Leary 215.

Stay tuned for the exciting conclusion of the Third Astley Belt in Part 15/Episode 109.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- The Croydon Advertiser (London, England), Jul 10, 1875

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 14, 21, Jul 19, Oct 8, 1878, Mar 2, 10, 1879

- Manchester Evening News (England), Feb 20, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Nov 29, Mar 4, 1878

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Jan 1, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jan 6, 26, Mar 1, 4, 8, 10, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Jan 30, Mar 1, 3-4, 9-16, 1879

- The Lancaster Gazette (England), Feb 19, 1879

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Mar 1, 1879

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Mar 4, 10, 1879

- Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), Mar 5, 1879

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Mar 11, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 8, 10-11, 14-16, 1879

- New-York Tribune (New York), Mar 8, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Mar 10, 1879

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Mar 10, 1879

- The Boston Weekly Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 11, 1879

- The Graphic (London, England), Mar 22, 1879

- Sheffield Independent (Yorkshire, England), Apr 3, 1879

- Aberdeen Evening Express (Scotland), Apr 4, 1879

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Apr 4, 1879