Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:02 — 32.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

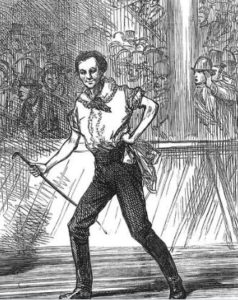

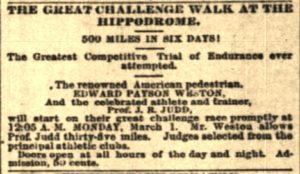

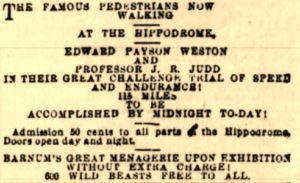

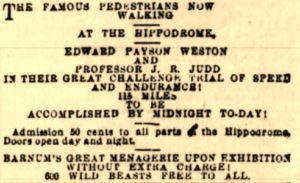

But with the failures, critics cried out that it was all just a money grab on the gullible public. It wasn’t a true race. It was said to be similar to watching “a single patient horse attached to a rural cider-press” going in circles for six days until it dropped. Experienced athletes and educated doctors believed that walking or running 500 miles in six days was an impossible feat. P.T. Barnum, “a sucker is born every minute,” did not care what the critics thought, knowing he had a winning spectacle to spotlight. He was right and would put on the first six-day race in history, billed as “the greatest competitive trial of endurance ever attempted.”

| Help is needed to support the Ultrarunning History Podcast, website, and Hall of Fame. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

P.T. Barnum promotes Professor Judd’s Six-Day Attempt

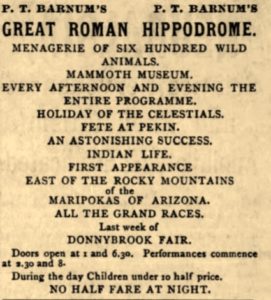

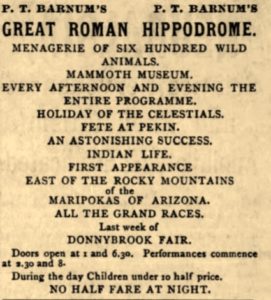

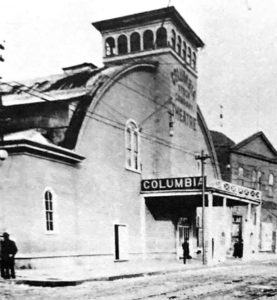

By December 1874, Barnum’s circus was back in full operation in New York in the Hippodrome for the winter season. It was lit by many lanterns, featured chariot races, and presented a menagerie of 600 “wild beasts.”

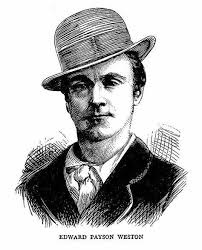

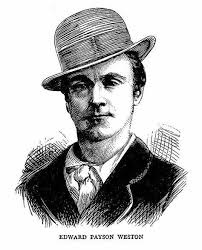

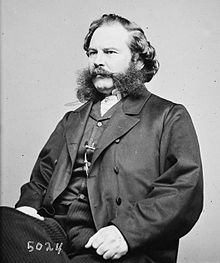

Barnum turned to a walker other than Weston and hosted “Professor” John R. Judd (1836-1911) at the Hippodrome. Judd had been a gym owner and trainer from Buffalo, New York but recently had moved to New York City. He had gained some fame training boxers and pedestrians and had previously issued a challenge for a walking match against Edward Payson Weston, which was ignored.

Judd’s former hometown wrote, “Judd is excessively muscular. His ‘professorship’ being not anything in the line of learning but simply that of gymnastics.” Another observer wrote, “He is a splendidly formed man, but with a figure better fitted for boxing or wrestling than for walking. He moves heavily and ploddingly, and on account of his great muscular development, he is obliged to keep his whole body in constant motion. He has great powers of endurance but is a slow walker.”

By evening of day five, Judd could not continue. “His left knee and his ankles swelled terribly during the day. Toward night he was suffering great pain. He continued to struggle until he had accomplished his 368th mile, when he sank exhausted and was carried to his room. He then claimed that he had sprained his ankle and abandoned the feat. The affair had been a failure, and very few spectators were present during the week.”

Judd’s hometown of Buffalo was disappointed in Judd’s failure and reported that ten days later Judd’s leg was still in “a precarious condition.” They concluded, “The difficulty with Professor Judd was his excessive muscular development, which over-weighed him. Mr. Weston on the contrary is very small and lightly built, having little or no muscle at all.”

Judd would not give up and soon would participate in the first-ever six-day race.

Weston’s Fourth Attempt at 500 Miles in Six Days

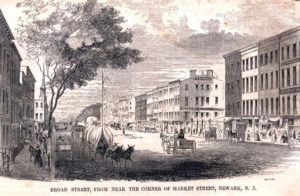

Weston had failed three times in New York City to walk 500 miles in six days. Because of the poor treatment he had received by the New York City press, he looked elsewhere for this fourth attempt and took his six-day attempt across the Hudson River to the Washington Street skating rink in Newark, New Jersey. Newark put out the welcome mat for him and promised to pay him well. He needed the money to pay off a large mortgage for a huge house that he had recently purchased in Kingsbridge, Bronx, New York.

This attempt was on a very tiny indoor track, sixteen laps to the mile. However, after measuring it closer by civil engineers, it was found to be 24 feet long and lap counters adjusted their distance calculations. Procedures required that every time Weston completed a lap in front of the judges, that the lap number was called off and crossed off the books, “while several others kept separate score sheets to check the record.”

The Start

Dr. Taylor had used an interesting treatment on Weston’s feet to avoid blisters. He “pickled” them prior to the event. “That is, he would let them soak in salt water for a long while at different times, and when resting during the walk he would bathe them in a similar preparation.”

Bribes and Threats

After logging another 75 miles on day five, Weston said he was approached by some people offering him thousands of dollars to throw the attempt. He told them to go away but then suspected that other “New York roughs” were plotting to sabotage his remaining effort by throwing pepper and other chemicals at him. The Newark mayor arranged for protection from the police and promised that if the peace could not be preserved, that he would call upon the military.

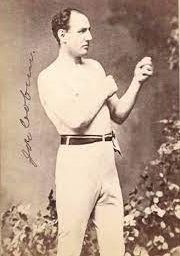

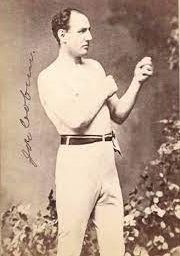

On the last day, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Joe Coburn (1835-1890) and others for plotting against Weston. Coburn was a prominent boxer. He and his gang had been in trouble with the law before for assault and were involved with gambling. (Two years later, Coburn was arrested in 1877 for the attempted murder of a policeman and served six years in prison). It is possible that all of these gang threats were in Weston’s imagination due to nervousness caused by lack of sleep. The next night he would again express worries that he would be assaulted.

Henry Clay Jarrett (1828-1903), the manager of Booth’s Theatre (1869-1965), had bet $2,000 on Weston reaching 500 miles. Jarrett sent messages of encouragement to Weston, and received a reply back, “Success assured. I am the hero of the hour. Have me a box for Monday night.” He received other telegrams from prominent lawyer and politician, Rufus F. Andrews, and W. H. Marston, a famous sailing captain, who both encouraged him.

During the last evening, the rink filled up with an enthusiastic crowd of about 6,000 people. Many prominent people attended including “almost the entire medical faculty of Newark.” Mayor Nehemiah Perry (1815-1881) of Newark walked with him a few laps but quit when he could not keep up, causing roars of laughter to come from the crowd.

During the final hour Weston was joined by the chief of police, Peter F. Rogers (1836-1915) and other offices who trotted around him, providing protection. Fifty men were required to keep the narrow track clear. “There was not an inch of room either in the galleries or on the main floor, and the announcements from the judge’s stand were awaited with breathless suspense. As each mile was called from the timekeeper’s desk, the general enthusiasm bubbled over into cheers and at times the noise of the band was lost for whole minutes amid the uproar.”

The Finish – 500 miles in Six Days

After walking 58 miles without a rest, finally the last lap for 500 miles arrived at 11:40 p.m. “As the six days’ trial was narrowed to the last strides, and the final step that measured off the greatest feat of physical endurance on record, he fell into the arms of friends who bore the hero in triumph to the stand.” He had walked his last mile in 11:57.

“The refreshing sleep of Sunday seems to have completely restored him and the peculiar drowsiness that possessed him during the last moments of his walk has, fortunately for him, passed away without injury to his system.”

Positive Reaction

In Michigan it was written, “We take it all back. We have been among them who have experienced some relief in denouncing Weston as a humbug and a habitual boaster who never accomplished what he professed his ability to do. But now that he finally succeeded, it is worthy of editorial mention. He is certainly persevering and plucky, and to accomplish the feat after so many discouraging failures is even a more creditable performance than the success of his first attempt would have been.”

In Illinois, they were convinced that his walk was legitimate after being a laughing stock from his past failures. “If there was ever a greater walk in the age of the world, we have no record of it. Weston has proved himself a first-class pedestrian, and it is to be hoped that he will try and keep his laurels green by not wearying the public with attempts at impossibilities.”

In Missouri: “Weston has been sneered at, laughed at, given all manner of names, but he has kept on trying. We congratulate the plucky pedestrian on the fair accomplishment of his task. No horse in the world could endure such an effort, and we doubt if there is another man in the world possessed of such excellent staying qualities.”

Negative Reaction

But the Newark Courier was highly critical of Weston in an article entitled, “Humbug Weston.” It read, “It is astonishing that this man Weston should be tolerated in any community.” The main criticism was that Weston would not submit himself to a true judged walking match against others. When would he participate in a race? “There are fifty gentlemen amateurs in this city who could walk the heart clean out of him at long or short distances.” Meanwhile, in Chicago a newcomer, Daniel O’ Leary had recently walked 200 miles in 36:29, invading Weston’s Pedestrian space and that city called O’Leary, not Weston, “the champion pedestrian of the world.”

The Courier said that instead of racing, Weston paraded around carrying a hat for innocent people to put pennies in. “Weston should procure a hand-organ and a monkey, and thus in a musical manner he could at least earn the pennies.” The article doubted his 500 miles were legit and concluded in a particular cruel way for that era. “Cannot someone in authority have him engaged as a mail carrier in the Indian country and pick him out a good scalping territory?”

Another newspaper in New Jersey was critical about betting on such endurance events. “Fools and their money are soon parted. Suppose next time he tries to eat a bushel of turnips in one sitting. Suppose he swallows a mackerel whole, bones and all, without winking?”

Despite the criticism, the most credible evidence showed that Weston had accomplished what people of the era thought was impossible and had never been accomplished by legendary Foster Powell who at started it all. The 500-mile barrier had been broken, ready for others to also achieve it.

The First Formal Six-Day Race

Professor Judd, seeking fame and fortune, seized on the doubt drummed up by Weston’s critics and issued a challenge on February 4, 1875, for Weston to compete against him in what would be the first six-day race in history. Judd wrote to, “Considerable doubt appears to be entertained as to your recent performance at the rink in Newark, and many would like to convince themselves of the ability of a human being to perform such a task.” Weston at first declined, mentioning that he had promised to next walk next against an Englishman. Judd countered, that he was indeed born in England.

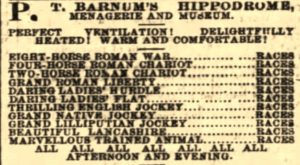

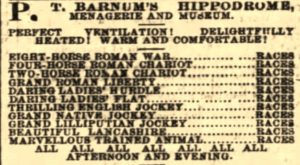

Weston would credit Judd 35 miles. No, Judd would not be given a 35-mile head start, he would be credited with 35 miles that he would not walk, requiring Weston to walk 35 miles further by the end of six days in order to win. The walking style needed to be “fair heel-and-toe walk.” Heavy betting occurred, about 4 to 1 in favor of Weston. “Both men had tents pitched in the ring to be used for rubbing down and resting.”

The Start

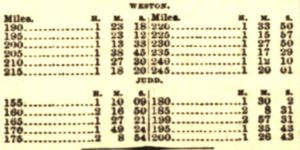

Day Two

The press knew that Judd was in trouble. “His system of training will need to come out strong pretty soon or it will be too late to win the race. The old proverb about the tortoise isn’t worth a pinch of snuff opposed to a hare like Weston, with somebody to wake him every hour.”

Day Three

Day Four

Day Five

On day five, Mullen suffered from a blistered foot and broke down quickly. He eventually quit at 4:30 p.m. reaching personally, 89 miles, bringing the challenger relay-tally to 341 miles. He blamed his failure on a lack of training and not taking care of his feet while competing. After Mullen left, Weston stopped to give a speech to the audience, boasting about his great performances as a pedestrian, and how this race came about.

A few hours later, George B Coyle (1844-1880), an unknown pedestrian who claimed to be the champion of Wisconsin, was brought out as a second replacement for Judd. He started his walk at 8:30 p.m. with a strong pace. At that point Weston retired to bed with about 364 miles, and a 23-mile lead. After a short rest, he came back out expressed confidence that he would out-walk the new competitor. He showed greater energy than at any time that day, finishing with about 370 miles. Coyle, not sleep deprived, kept up his walk late into the night after Weston retired.

Day Six

Toward the end of the event, a controversy arose. Mullen boldly came out on the track again to get attention, trying to make up for his embarrassing defeat. He started giving a fast-walking exhibition for the audience with permission from the Hippodrome managers. Weston threw a fit, not wanting Mullen to take the spotlight off him. He demanded that Mullen be removed from the track and warned that if not, he would stop. Weston made his threat good and stopped walking until the police removed Mullen. This caused “considerable dissatisfaction among the rowdy element in the audience.”

The Finish

At the end, Weston reached 431 miles. Coyle reached 95 miles during his turn, bringing the challenger relay total to 436 miles (including the 35-mile handicap). Weston claimed he could have easily reached 500 miles but took it easy once Judd had quit. His friend, New Jersey politician, Rufus F. Andrews, said that Weston never intended to reach 500 miles unless pushed by his competitor because he had an injured hip.

The final tally of the first six day race was:

- Weston – 431 miles

- Judd – 222 miles

- Coyle – 95 miles

- Mullen – 91 miles

Critics of Weston Silenced

One observer broke down this first six-day race and gave huge credit to Weston’s crew. “Weston was splendidly handled and availed himself of every advantage that could be received from good medical and bodily attendance. His regulations were stringent, and everything was ready for him on the slightest notice. Judd, on the contrary, depended too much on himself and his own powers of endurance.” Also Weston had built up strength with all of his extreme walks during the past year and developed the ability to regain strength with only two to three hours of sleep.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources

- Andy Milroy, The History of the 6 Day Race

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- P. S. Marshall, Weston, Weston, Rah-Rah-Rah!

- Toms Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- William L. Slout, Rags to Ricketts and Other Essays on Circus History

- T. Barnum, Barnum’s Own Story: The Autobiography of P.T. Barnum

- Fayette County Herald (Washington, Ohio), Aug 24, 1871

- Matawan Journal (New Jersey), Dec 5, 19, 1874

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 24, 1874

- New York Times (New York), Dec 19-21, 1874, Feb 25-27, Mar 2-7, 1875

- The Times Herald (Port Huron, Michigan), Dec 24, 1874

- The Memphis Reveille (Missouri), Jan 7, 1875

- The Rutland Daily Globe (Vermont), Dec 9, 1874

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Dec 11, 1874

- The Cairo Bulletin (Illinois), Dec 13, 1874

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Oct 15, Dec 25, 1874

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Dec 12, 21, Mar 3, Apr 12, 1874

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Nov 7, Dec 14, 22, 1874

- Boston Evening Transcript (Massachusetts), Dec 14, 1874

- Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 21, 1874

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 24, 1874

- Carbondale Advance (Pennsylvania), Dec 26, 1874

- The Luzerne Union (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Dec 30, 1874

- Shelby County Herald (Missouri), Jan 6, 1875

- The Waukegan Weekly Gazette (Illinois), Jan 16, 1875

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Jan 3, 1875

- The Memphis Reveille (Missouri), Jan 7, 1875

- Columbus Era (Nebraska), Feb 20, 1875

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Feb 13, 1875

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 1-7, 1875

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Mar 5, 1875

- The Sun (New York, New York), Mar 5, 1875

- New York Tribune (New York), Mar 5, 1875

- The New Orleans Bulletin (Louisianna), Mar 12, 1875

- Hamilton Daily Times (England), Mar 2, 1875