Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:19 — 32.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

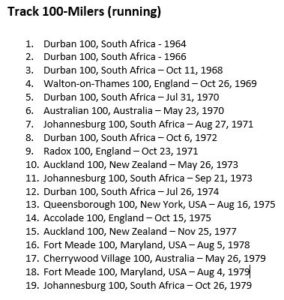

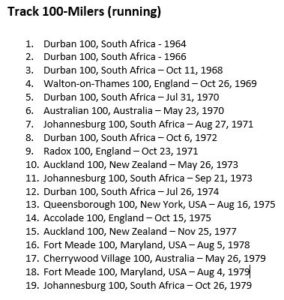

During the 1960s and 1970s, most of the 100-mile races were held on oval tracks. Additionally, 100 miles were achieved during 24-hours races, usually also held on tracks. Running for 100 miles on an oval track seemed like an extreme oddity back then, even as it does today.

During that period, there were 19 known track 100-mile running races held worldwide, that were not also 24-hours races. In addition, there were many other 100-mile racewalking competitions in both England and America where walkers sought to become a “Centurion” by walking 100 miles in 24 hours of less (see episode 63).

The first modern-era track 100-miler (running) was held in Durban, South Africa in 1964 won by Manie Kuhn in 17:48:51. In America, the first track 100 was held in 1975 in New York, the Queensborough 100, won by Park Barner in 13:40:59 (see episode 66).

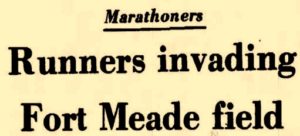

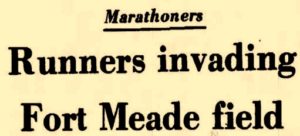

Beginning in 1978, an important track 100-miler started to be held, that became the premier track 100-miler. The race was held on an military base at Fort Meade, Maryland in America. It would be held there for twelve years. This 100-miler was dominated by Ray Krolewicz of South Carolina, who won it six times. Sadly, this race has been mostly forgotten in the annuls of ultrarunning history.

|

Fort Meade

24-hour Relays

The base opened their doors to runners and kindly made facilities available including restrooms and showers. Nick Marshall wrote, “This was an era when many military bases had very open policies. They had guardhouses at the gates, but security was often minimal. Showing I.D. was not required before getting on the Fort Meade base. We would just pause at the gate and mention that we were running the race and they would wave us through. It was definitely very casual.”

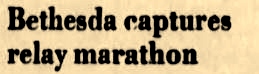

1973 Fort Meade 24-hour Relay and 50-miler

That year the race was made into a memorial race for that late Lt. Colonel Edward D. Carroll, who was a member of the Road Runners Club. The race was held in the heat of the summer beginning at noon on August 4, 1973 and included some military teams. The event attracted 206 runners

![]()

![]()

A men’s team from the Bethesda Track Team went the furthest, 277 miles, thought to be the best in 1973.

For the first time at Fort Meade in 1973, a special solo 50-mile race was also held at the event for ultrarunners on that track with a 12-hour cutoff. There were eight starters, but the drop-out rate was very high. There was only one finisher, Ed Jerome (1943-1982) of Annandale, Virginia, who covered 50 miles in an impressive 7:41. He would place 4th at the 1975 JFK 50. He finished 140 marathons before his sad death in about 1983 when he was killed by a motorist while he was riding a bicycle after dark, training for an ironman.

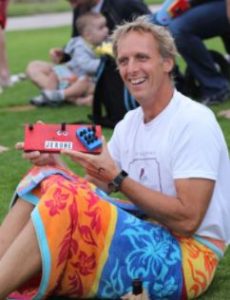

1974 Fort Meade event

A 50-mile race was again held in 1974. A racewalker, Israeli Olympian and world record holder, Shaul Ladany (1936-), participated and finished just minutes after the winner in just over 8 hours. Ladany had survived both the Holocaust and the 1972 Munich massacre. He set the world walking record for 50 miles in 1972 with 7:23:50. A record that still stands. In 2020 he was 84 years old and still walking.

![]()

![]()

The winning team reached 280 miles, a new Maryland state record. Hill’s team reached 267 miles, just two miles ahead of a team of marines.

In 1974, the world 24-hour relay record was raised to 297 miles by the Edinburgh Athletic Club in Scotland. Soon, so many annual 24-hour relay events were being conducted that yearly world rankings were even kept and published by Runners World Magazine.

The Fort Meade 50-miler takes hold

In 1975, a team from Wheaton, Maryland broke the 24-hour Fort Meade relay event record with 281 miles. A 50-mile event was again held.

Nick Marshall (1948-) of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, competed in the 50-mile event that year and recalled, “The ultramarathon participants were outnumbered by the 30+ relay teams. It was sort of daunting to have all sorts of fast milers whipping by us like most of them were Yiannis Kouros. Even if you were leading the 50-mile at a strong pace, there were still a bunch of other guys around you running much faster than you.”

Tom Osler (1940-) won the 1975 50-miler in 5:49:14. In 1976, Marshall won in 5:54:08, followed by Don Marvel (1943-2015) of Easton, Maryland, in 6:23:00. Larry Jarner competed in both the 50-mile run and the 24-hour relay.

The 1977 50-miler was a rematch between Marshall and Osler. They waged a seesaw battle in the early stages when Marshall reached the marathon in 2:54:30 and extended to a two-lap lead. But blisters took a toll and he dropped out at 38 miles. Newcomer Jim Czachor (1948-), of Franklin Square, New York stormed past Osler for the win in 5:44:30. Osler finished in 5:51:13.

A walking relay team participated that year. “Weaving through the masses of runners were the herky-jerky movements of the Potomac Valley Walkers, who were headed to a national race-walking mark. Their total of 168 miles, 1,700 yards bettered the old standard of 155 miles, 1,181 yards set by the Capitol Walkers, from which the Potomac Valley club descended.”

The 1978 Fort Meade 100-miler

Track 100-milers were rare and odd to those who watched. One observer described the setting, “The proverbial sea of tents that offer temporary relief for the physically and mentally weary athletes surrounds the track and adds a colorful dimension to the otherwise dreary oval. Support crews (a.k.a. lap counters, shoe changers, muscles massagers, motivationalists, etc.) line the track with clipboards in hand, pencils poised and watches ticking away the endless seconds, just living for the moment when their man barks, ‘water, next lap.’” A few soldiers would come out and do workouts in the stadium, but few came as spectators.

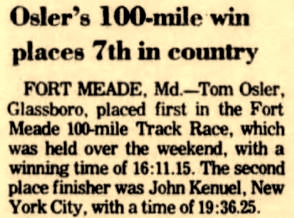

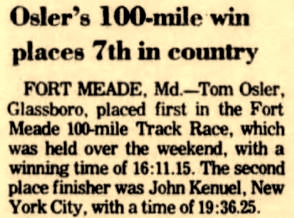

Tom Osler (see episode 67) won the inaugural event with 16:11:15 for the second 100-mile finish of his famed ultrarunning career. John Kenul (1943-2005), of Brooklyn, New York, came in second with 19:20:30.

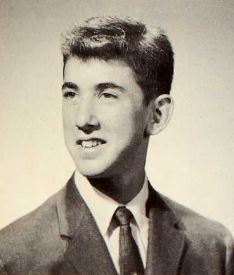

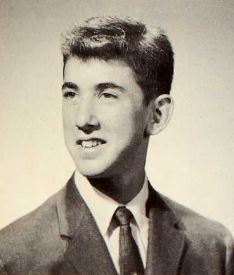

John Kenul

John “Johnny” Kenul needs to be mentioned in this 100-mile history. He became one of the most prolific early 100-miler runners and the most consistent in the sport, rarely not finishing a race. Kenul, born in Genoa, Italy, immigrated as child to America, and lived in Brooklyn, New York. He ran cross-country and track in high school at Power Memorial Academy. He went on to worked at the post office on Manhattan.

Kenul became a very early ultrarunner in the New York City area, who ran his first ultra in 1969, the 37.5-mile Peekskill Yonkers race put on by Ted Corbitt’s New York Road Runners Club. He was a fixture at the annual Metropolitan 50 Mile race in Central Park. He was a mid-pack runner, never placing high in a serious competitive field, but he loved running and running ultras often. He would train about 6-7 miles per day along with a 20-mile run once a week. If he felt tired, he would take a day off. He became a member of the Prospect Park Track Club.

Kenul ran in the Fort Meade 50 in 1974 and told a tragic tale. “The race started at 6 p.m. My lap counter fell asleep deep into the night while I was running. I ran for hours and not a lap was recorded. I never knew how far I ran and thus did not finish.”

The 1978 Fort Meade 100 was Kenul’s first of more than 50 career 100-mile finishes. With his solid sub-20-hour finish at Fort Meade, he became hooked on running 100 miles and more. By 1984, he claimed that he had finished 100 ultramarathons and by 1990 reached 200 with only four DNFs. If there was an ultra held in the East during those years, Kenul was likely there and finished. His favorite races were the multi-day races put on by the Sri Chinmoy Marathon team. He also finished eight Vermont 100s.

Ray Krolewicz, of South Carolina, remembered Kenul and said, “Johnny was a good friend of mine. He didn’t drive and had a heavy accent. He was a very compact strong runner and ran really fast in his youth. By the time I met him he was slowing down some. There were times I would go pick up Johnny and drive him to the races. The was a man of impeccable integrity. If he was running on the sidewalk and thought the course had been measured on the road, he’s stop on the curb to go around a corner, so he didn’t cut. He was one of my early mentors and heroes.” On 9-11, Kenul worked at the post office near the World Trade Centers. “He was on the porch of the post office and did not realize that the building had collapsed until looking closely at the smoke column.”

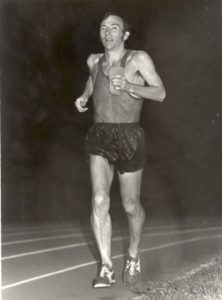

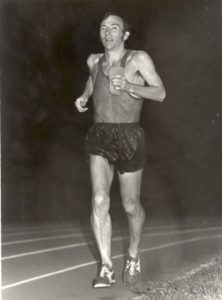

1979 Fort Meade 100

At the 1979 Fort Meade 100, Don Marvel (1943-2015), a high school teacher from Easton, Maryland, was a favorite at Fort Meade 100 with nine starters. He stayed close to Peter Monahan (1934-), age 44, of Bethesda, Maryland for 70 miles until Marvel had to drop out. Monahan continued on to the win in 15:42:02. It was his third 100-miler in three months. He had also won the Old Dominion 100 (to be covered in a future episode) and had placed ninth at Western States 100. Other finishers at Ford Meade were John Emswiler (1953-) of Pennsylvania in second with 17:05:30, just ahead of ultrarunning new-comer Ray Krolewicz (1955-) of South Carolina, in third with 17:16:55, and Nace Magner (1956-), of Pennsylvania, in 18:14:30. Five others did not finish.

Ray Krolewicz

Krolewicz went off to college and graduated from the University of South Florida and the University of South Carolina. He began a life-time high school teaching career and also coached soccer, basketball, and track.

Krolewicz gained running experience. “I ran a handful of marathons and other races through the 70s and then I actually started training in 1978 and wanted to see how fast I could cover various distances. The ultras were almost an accident.”

In 1979 he went to run the Boston marathon. At the start, he had a chance meeting with 70-year-old San Francisco running legend, Walt Stack (1908-1995) who had recently finished Western States in 1978, in 38:57:00. Krolewicz heard the word, “ultramarathon” for the first time from Stack, who invited him to try running one, at Lake Waramaug in Connecticut. Krolewicz hitch-hiked to the race, did well, and later in 1979 began his long association with Fort Meade. He returned in 1980.

1980 Fort Meade 100

Dick Good (1929-2018) and Bob Rothenberg (1945-) put on the race. For the first time that year a computer was used by Rothenberg to calculate the finishing positions and awards. Rothenberg was the track and cross-country coach at Fairmont High School and complained that the news usually covered the event as a “freak show” instead of a sporting event. He said, “I consider it a distance-running carnival.” It certainly did look like a carnival with about two dozen tents pitched alongside the track for runners and their crews. “At planned intervals, runners in the 100-miler would flop onto the backs in their ‘pit areas,’ gratefully sponging and squeezing cool water over their bodies, receiving a glucose fix of snacks like Twinkies or soft drinks and then picking up where they left off with 50 miles to go.”

In 1980 Krolewicz ran the 100-miler again, crewed by Don Marvel who had injured his back recently at an earlier 100-miler. As in past years, the heat really was the main factor over the race. Don Paris, a New York physician, dropped out at 30 miles because of dehydration after losing about 15 pounds. Dr. John Newdorp (1910-2001), 69, from Oakton, Virginia with good experience treating heat stroke at ultras, looked after the 100-miler runners. He said, “They begin to develop symptoms. They feel nauseated, get headaches, begin suddenly to feel very tired. Some of them will begin to weave around.”

Ed Foley (1949-) of Lovettsville, Virginia, led for the first 32 miles and then Krolewicz took over the lead. One year Foley tried to run each mile no faster than six miles an hour, ten-minute miles. If he finished his mile a little faster, he would sit and wait, just like a precursor to the backyard ultra format decades later.

MacMillan would make it to 85 miles. He recalled that the large digital clock to be used by lap counters wasn’t working so they resorted to having someone call out the time every five seconds through a microphone and loud speaker. Ron Talbert of Baltimore recalled, “I ran four of those 24-hour relays during the early 80’s. The 100 miler started concurrently with the relay at noon. The 50-miler started at 6:00 p.m. I marveled at the ultrarunners. They hugged that inside white line on their laps. We would just go around them on the right when we passed them.”

Krolewicz continued in the 90-degree heat. They had a horse trough full of water and Krolewicz jumped in it several times to cool down. He was used to running in hot and humid conditions and would always be dumping water on his head.

Krolewicz remembered a strange occurrence one year. “Somebody came early afternoon when it was very hot and started to scream at the race director and runs for them to stop. Two runners had died earlier that morning in a ten-mile race nearby fearing that the runners at Fort Meade would also kill themselves.”

Krolewicz’ cool-down strategies worked and went on to win in 15:35:30, sprinting the last lap in an amazing 61.4 seconds. He then took over clock duty, calling out times. John Emswiler (1954-) of Pennsylvania finished second in 16:31:10. Six runners did not finish. For Krolewicz, that was the first of six wins at Fort Meade 100. He was dominant on the hot and humid track.

Later Years at Fort Meade

In later years, the Fort Meade 100 would attract many of the great eastern ultrarunners of the time including Paul Soskind, Dan Brannen, Wes. Emmons, and Neil Weygandt. Later in 1981, Cahit Yeter of New York would set the all-time best at Fort Meade with 14:46:52. Krolewicz won again in 1982. In 1983, the accomplishment that received the most attention was a two-man 24-hour ultra relay accomplished by elite ultrarunners, Dan Brannen and Neil Weygandt. Their adventure will be told in the next episode, episode 76.

In the early ’80s, many ultras were conducted on the honor system. At Ford Meade for several years, crews kept their own lap counters sheets. Peter Monahan, a D.C. attorney, the 1979 Fort Meade 100 winner, was back again one year. He had been suspected of cheating his races including his Old Dominion 100 and Fort Meade 100 victories in 1979. At Fort Meade, Krolewicz brought his brother to the race who kept a lap sheet on Monahan. Sure enough, the lap counts kept by Monahan’s crew were exaggerated. This was reported to race director Dick Good, who then started keeping track of Monahan’s laps from his race director tower. He also discovered discrepancies, confronted Monahan who then got angry and left. He soon gave up the sport.

Krolewicz remembered some “excitement” during the races in the late 1980s. “I won the race three years in a row, ’85, ’86, ’87. In 1988 I left early because it was raining and lightning. A couple years earlier, 1986, when my son John was ten years old and crewing for me, there was an hour and a half delay because of lightning. John was over by a green electrical boxes and lightning hit that box and tumbled him over. I took an hour nap during the delay, and then finished in 19:51:11, not including the delay.”

Race director Dick Good reported, “The rains came, torrential rains that flooded the track, the lap counters, and everything else, including the clock. The storm let up and the participants could return running, but it soon returned, this time accompanied by lots of lighting. This caused the clock to stop working, and the race was put on hold for one hour and thirty-two minutes.”

In 1987, Krolewicz won again and explained, “In 1987 my finish time was my wife’s birthday number, 17:57:07. I always used to play with numbers. Her birthday was July 17, 1957.” In 1984 he finished at 23:23:23 on purpose. For one of those years, he ran non-stop for 88 miles, the most continuous miles ever during his career.

He said, “At mile 88, one of the relay teams brought in bunch of food including fried chicken that smelled so good. I went and sat in a lawn chair, ate a piece of fried chicken and a jelly donut, and jumped up and did my last 12 miles. That was my longest actual non-stop run, running every lap.”

In 1988, several veteran runners including Krolewicz and Trishul Cherns, quit the race early because of another terrible thunderstorm. It was one of Krolewicz’s few DNFs up to that point. 1989 was the last year the 100-miler was held at Fort Meade, again won by Krolewicz. The 100-mile race was not held for the next couple years.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- Fort George G. Meade

- For Meade Documentary

- Nick Marshall, 2019 email on the history of the Fort Meade races.

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Aug 16, 1973, Sep 6, 1974

- Daily News (New York, New York), Aug 18, 1975

- The Capital (Annapolis, Maryland), Jul 30, 1973, Aug 5, 1975

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Aug 6, 1973, Aug 7,12, 1975, Aug 16, 1976, Aug 4, 1980

- Nick Marshall, 1977, 1978 Ultradistance Summary

- The Washington Post (Washington D.C.), Aug 8, 1977

- Howard County Striders Newsletter, 1985

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Oct 1986, Oct 1988, May 1990, Nov 1993, Oct 1995, Oct 2005

- In honor of John Kenul

- Interview with Ray Krolewicz, Mar 24, 2021

- Conversation with Shaul Ladany, Olympian who Survived the Holocaust & Munich Massacre