Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:55 — 34.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

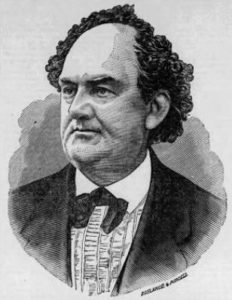

The ultimate showman, P.T. Barnum of circus fame, was surprisingly the first serious ultrarunning promoter and established the first six-day race in America. He was famous for the saying “There’s a sucker is born every minute,” and figured out how to get America to come out by the thousands to watch skinny guys walk, run and suffer around a small indoor track for hours and days as part of his “Greatest Show on Earth” presented in the heart of New York City. In this episode, details of Barnum’s connection to ultrarunning history are told for the first time.

The ultimate showman, P.T. Barnum of circus fame, was surprisingly the first serious ultrarunning promoter and established the first six-day race in America. He was famous for the saying “There’s a sucker is born every minute,” and figured out how to get America to come out by the thousands to watch skinny guys walk, run and suffer around a small indoor track for hours and days as part of his “Greatest Show on Earth” presented in the heart of New York City. In this episode, details of Barnum’s connection to ultrarunning history are told for the first time.

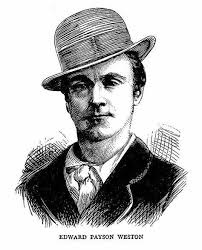

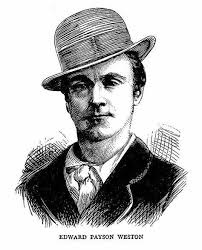

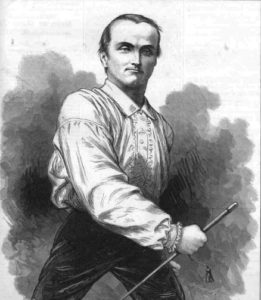

In part one of this six-day series, Foster Powell started it all in 1773 in England, seeking to reach 400 miles in less than six days. In part two, nearly a century later, the challenge was restored in America with the famous walker Edward Payson Weston, who was both cheered and ridiculed. As this third part opens, Weston seeks more than anything to reach 500 miles in six days, which had never been accomplished before. He had failed in his first serious attempt, reaching “only” 430 miles and was called by some, “The Great American Fizzler.” P.T. Barnum soon enters the story to lend support.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast, website, and Hall of Fame. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

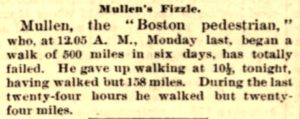

Edward Mullen Seeks 500 Miles in Six Days

It was reported, “Mullen has never, previous to the present time, engaged in any walking match for any long distance, the longest race hitherto being twelve miles.” Mullen began his pedestrian career only a year earlier in July 1873 at Beacon Trotting Park, Boston, when he won a short-distance walking race. That was the first of many impressive wins up to ten miles. But it seemed rather bold for him to go after the 500-mile six-day barrier.

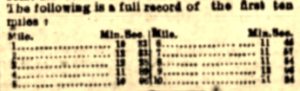

The track for his attempt was said to be 17.3 laps to a mile (305 feet). He began his quest at 12:24 a.m. on June 15, 1874. “Mullen was dressed in full walking costume, consisting of white Guernsey, blue silk trunks and white hose, with Oxford shoes. He is somewhat slimly built, is about five feet ten inches high and weighs 130 pounds. As he turned to commence his journey, he started off somewhat slowly, his step, however, being elastic and springy.”

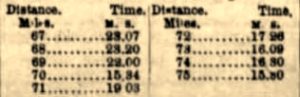

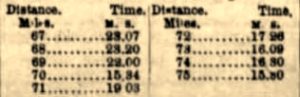

He finished his first mile, in a very surprisingly fast time of 7:22. On day one, he accomplished the 115-mile 24-hours task, beating Weston’s 115-mile time by five minutes. At that point he collapsed and had to be carried off the track by his backers. By day three, the determined Mullen had reached 233 miles on very swollen legs, one mile ahead of Weston’s failed pace.

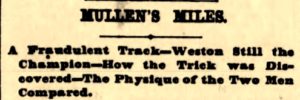

Fraud Detected

Mullen claimed innocence, that he was unaware of the mismeasurement and continued walking. He wrote a letter to the Herald complaining bitterly about the accusations against him and the letter was posted in the hall for all the spectators to read. Even with this discovery, his timekeepers did not correct the mileage in their books. He claimed to reach 365 miles after day four. With poor math skills, Mullen walked an extra 30 laps (1.4 miles) in 17 minutes, thinking that would make up for what he thought was a minor track measurement error.

After six days, he finished in front of only 250 people, and claimed that he reached 434 miles. In reality, he did not come even close to 400 miles, at most 343 miles, and the entire event was fraudulent. If it were more widely known, it could have torpedoed the future glory days if Pedestrianism before it even started. Mullen vowed to try again on a properly measured track.

P. T. Barnum Promotes the Six-Day Challenge in America

The Hippodrome

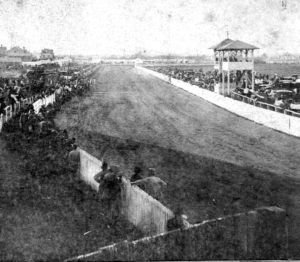

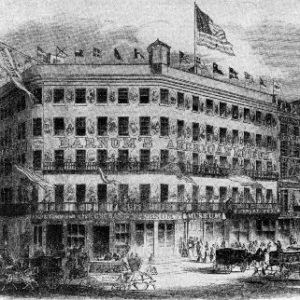

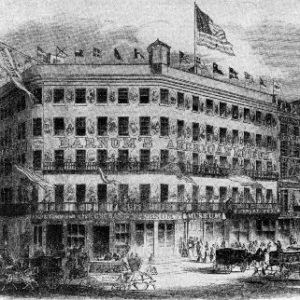

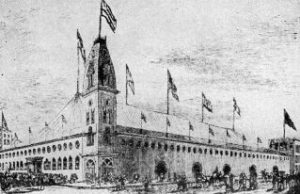

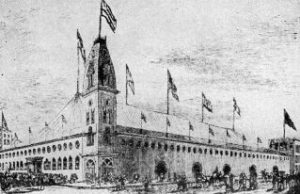

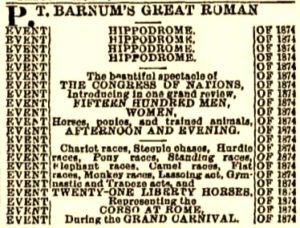

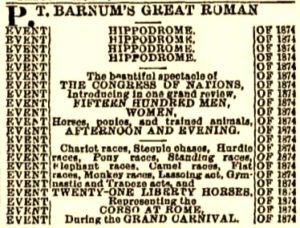

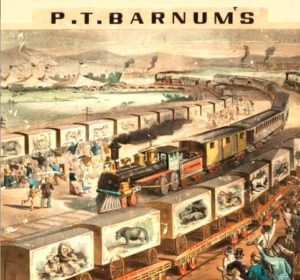

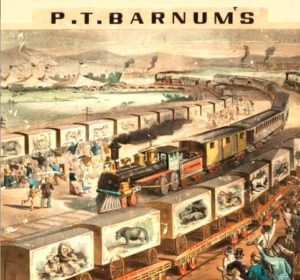

New York City was starved for diversion from harsh everyday life. In 1874 Barnum established his travelling circus on an entire New York City block between 4th and Madison Avenue, between 26th and 27th Street. Today, the New York Life Building stands on this spot on Manhattan, which was the scene for a decade of the earliest American six-day races.

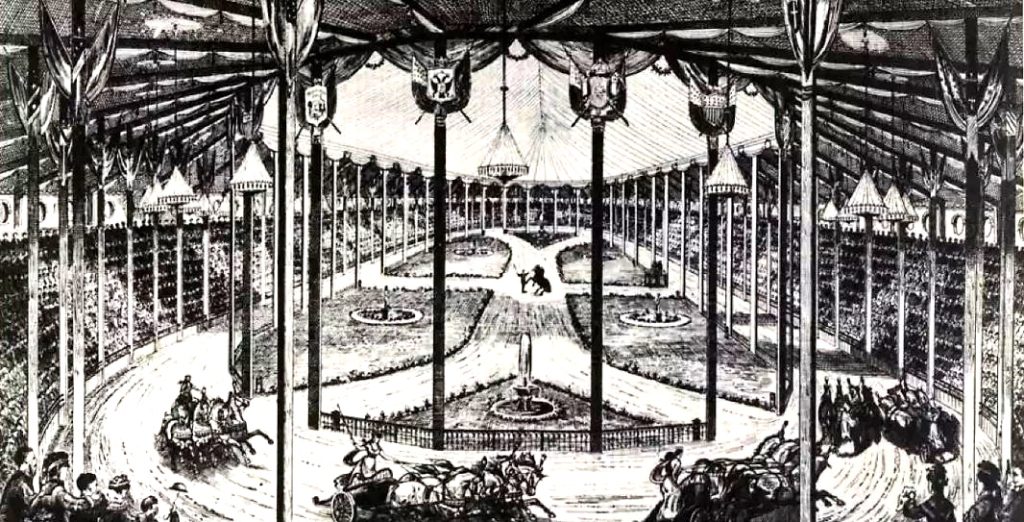

William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) owned the property and leased it to Barnum. The site had been used by an old Harlem and New Haven railroad depot. Barnum rented the train sheds there, opened a museum, and constructed a “Hippodrome.” This was initially an open-are venue with a removable light canvas roof, giving it a “big-top” feeling, the first stadium with a retractable roof in the United States. It was a rather simple structure consisting of an elongated dirt oval surrounded by wooden bleachers. Balconies that hung low over the main floor were later installed, bringing the venue’s capacity to ten thousand. It was enclosed by a three-story brick wall. The buildings constructed cost Barnum $200,000 (4.8 million in today’s value).

The performance area was a massive 400 feet by 200 feet, larger than a football field. It included performance rings and a track to host chariot races. Barnum’s new creation was opened on April 27, 1874. It was soon reported, “Barnum’s Hippodrome with its rich pageants, displays of strange animals and exciting races, continues to attract mammoth audiences.”

A mobile Hippodrome was also created, a series of tents that could be moved from city to city that could accommodate 10,000 spectators. The traveling tent Hippodrome would go to Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati. But it was at New York City, where he created a Hippodrome using a building, and it stayed there for about a year.

Barnum’s First Short Pedestrian events

For the next evening, the race was expanded to ten entries. But only five finished. J. Downie of the New York Caledonian Club won the race by six inches, in 5:13. That night a half-mile walking race was also held with fourteen walkers. Prizes included medals, diamond and gold lockets, and silver goblets.

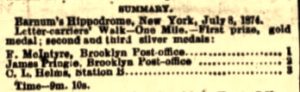

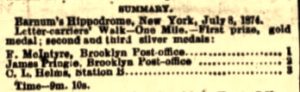

Postman Races

![]()

![]()

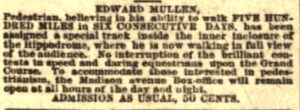

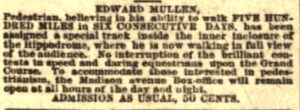

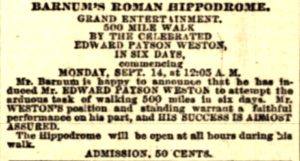

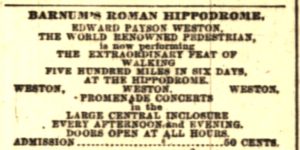

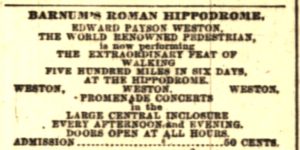

Barnum promotes the Six-Day Event

![]()

![]()

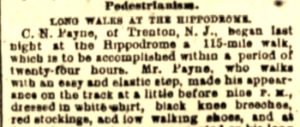

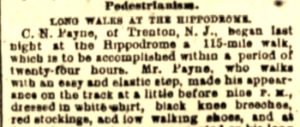

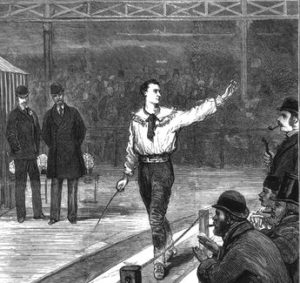

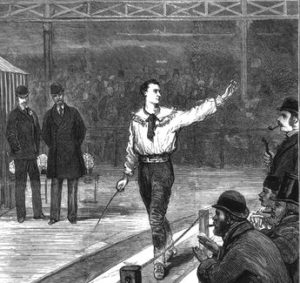

Mullen was described as being a small, think man, “with more activity and tenacity of purpose than physical strength.” His walk began at 12:05 a.m. on July 20, 1874. He reached 40 miles in eight hours and then stopped for breakfast and a rest for 45 minutes. His mile times were degrading toward 15-minute miles

Mullen reached 51 miles in the afternoon and then rested as the “Grand Congress of Nations” was presented in the Hippodrome with hundreds of performers. He then continued going at a stronger pace. “The pedestrian does not propose attempting any extraordinary bursts of speed, but simply intends to keep up to his average of a little more than 83 miles a day.” It was surprising to see that so many spectators stayed between the major performances to watch Mullen walk.

As Mullen walked in the afternoon and evening, amateur athletic contests took place at the same time including pole-vaulting, rope-climbing, standing long jump, weightlifting, pole-climbing, shot put, wrestling, high jump, foot boxing, and various footraces. It was a rough first day for Mullen. Rain fell for three hours and penetrated through the canvas tent cover, making the track heavy with mud. By the end of the first day, Mullen only reached 66 miles. “He is walking rather slow but appears to look well.” But another account wrote, “His left knee is much swollen and it is believed he will fail.” It was rumored that he would be replaced by another pedestrian.

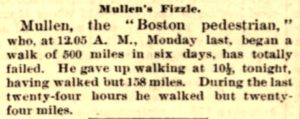

On day two, Mullen struggled, but during the morning clocked an 8:20 mile that encouraged his backers. But he only completed another 33 miles on day two, for 100 miles total and complained about his sore knee. His condition improved on the next day, but his miles were still slow with a total of only 140 miles in three days. “Mullen continues to drag along without the least possibility of completing 500 miles within six days. His knee is still swollen, and his rest are very frequent.” After walking only 18 miles the fourth day, he gave up (or was fired) at 10:30 p.m. for a total of 158 miles in four days.

Sadly, on the next evening, a lady riding in a hurdle race became fatally injured when her horse hit a hurdle, did a complete somersault and she crashed into the hurdle too. She died a couple days later. It had been the fourth death from accident in the Hippodrome during the past month. Safety for performers obviously was a serious problem.

Cornelius Payn walks in the Hippodrome

The Hippodrome Closes for the Summer

While the circus was away, it was planned to transform the immense New York Hippodrome into a winter theater for the exhibition of “monster equine dramatic performances.” This required Barnum to replace the canvas roof for a light iron roof, about eight feed higher, that would support the weight of snow and include three rows of movable glass skylights that could still allow building ventilation. The interior of the building would receive no changes except for the installation of seventeen huge furnaces. They hoped to reopen in six weeks, by September 20, 1874.

Even with this planned work going on, a fall season was scheduled to allow a portion of the arena to be used for events such as plays, tournaments, and yes pedestrian exhibitions.

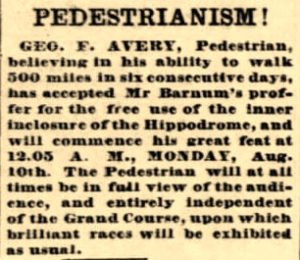

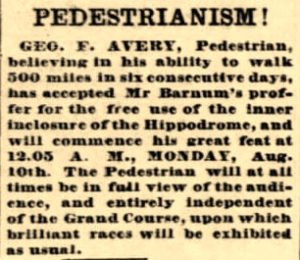

George Avery Attempts 500 miles in the Boston Hippodrome

Avery had some pedestrian experience. He started his walking career at the early age of eighteen in Boston, competing at 25 miles and then stepped up to 100-milers. In June 1874, he walked 100 miles in Manchester, New Hampshire at a riding park in 21:40.

At the Boston Hippodrome, Avery started his 500-mile quest on August 10, 1874, at 12:05 a.m., but became quite ill during the day. It was observed, “It has been evident from the start that he was in very poor condition to perform his allotted task.”

On day two, he reached 78 miles by breakfast at 7 a.m. But during the afternoon, he “broke down” at the entrance of “the Congress of Nations” after reaching 101 miles in a very slow 39:18. “He had an attack of vomiting and his attendants from his condition were at once satisfied that he could not safely continue the attempt. His condition did not improve, and the attempt was given up.”

With yet another 500-mile failure, other pedestrians declared that no man living could walk the 500-mile distance in six days. The press was kind and wrote, “The attempt was squarely made, and if he had been in good condition, the result would have been far different if not entirely successful.” Avery declared that he would try again in two months, and he hired the English pedestrian, John Haydock to handle him. But Avery later gave up his attempts at six-days, continued his pedestrian career at shorter distances, and called himself, “P.T. Barnam’s Great Pedestrian.”

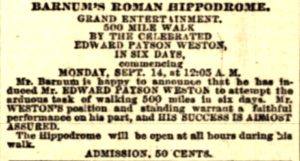

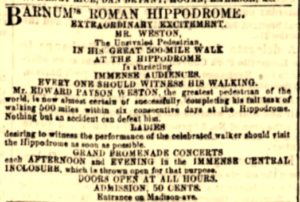

Barnum promotes Weston’s Second Six Day Attempt

![]()

![]()

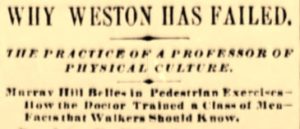

Reaction to Weston’s Failure

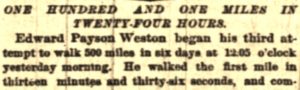

Weston’s Third Six-Day Attempt

![]()

![]()

He revived again, and as the band played was bouncing along at a lively pace, but whenever the band would stop, his rhythm of stride was slow. “After a time, his legs began to grow numb with exertion and then he resorted to whipping them with the little riding switch he carried.” On day four he reached only 286 miles and, in the end, finished with 345 miles. His doctors said he had a severe infection in his left foot.

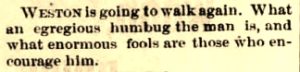

Strike Three – Weston is Out?

The Times Union in Brooklyn agreed, “The public has had quite enough of this sort of thing. The truth is this walking business is fast degenerating into humbug.” The paper was convinced that Weston was unequal to the task of walking 500 miles in six days. “Let us have more walking, but less Westonism.” The Brooklyn Union accused Weston of having “an insane delusion” that he could accomplish the feat. The Brooklyn Argus thought Weston could have a bright future but would not experience it until “somebody saws off his legs.”

The New York Herald wanted Weston to go away, wishing that his next 500-mile attempt would be a point-to-point walk away from New York City. “If he will go away as far and as fast as his legs can carry him and stay away, we shall never call him a humbug or a nuisance anymore, but calmly forgive and forget him.” In Buffalo, New York, they called him, “the greatest and most offensive of American humbugs.” It was suggested that Weston next try to walk around the globe, starting from New York City, “and go halfway around, and there stop till sent for.”

Would Weston ever succeed in walking 500 miles in six days? Stay tuned for the next part in the six-day history.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources

- Andy Milroy, The History of the 6 Day Race

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- P. S. Marshall, Weston, Weston, Rah-Rah-Rah!

- William L. Slout, Rags to Ricketts and Other Essays on Circus History

- T. Barnum, Barnum’s Own Story: The Autobiography of P.T. Barnum

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jul 9, 1874

- New York Times (New York), Jun 28, Jul 17, Aug 14, Oct 9-10, 1874

- New York Tribune (New York), Jun 16-20, Jul 30, Sep 16, 1874

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Jun 15, 19, 1874

- The Vermont Record and Farmer (Brattleboro, Vermont), Jun 26, 1874

- The Brooklyn Sunday Sun (New York), Jul 19, 1874

- The Omaha Evening Bee (Nebraska), Jul 21, 1874

- The Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), Jul 21, 1874

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Jul 21, 1874

- The Yonkers Gazette (New York), Jul 18, 1874

- Boston Evening Transcript (Boston, Massachusetts), Jul 21-23, Aug 3, 12, 1874

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Jul 22, 1874

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jul 24, 1874

- The Muscatine Journal (Iowa), Jul 24, 1874

- The Herald and Torch Light (Hagerstown, Maryland), Jul 29, 1874

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Jun 22, Aug 3, 6, 27 1874

- The Rutland Daily Globe (Aug 1, 1874)

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Sep 14, Oct 9, 12, 15, 1874

- The Brooklyn Sunday Sun (New York), Oct 11, 1874

- The Luzerne Union (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Sep 23, 1874

- The Sun (New York, New York), Jul 21, Sep 14-25, Oct 9, 1874

- The United Opinion (Bradford, Vermont), Oct 3, 1874

- The Pall Mall Gazette (London, England), Jun 4, 1874

- The Daily Milwaukee News (Wisconsin), Sep 20, 1874

- Reading Times (Pennsylvania), Oct 5, 1874

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Oct 10, 1874

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Oct 8, 1874

- Kings County Rural Gazette (Brooklyn, New York), Jan 24, 1874

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Oct 14, 1874