Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:06 — 31.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

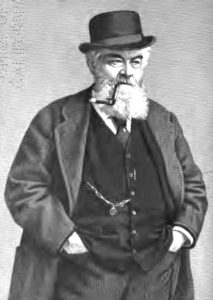

In 1878, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago was the undisputed world champion of ultrarunning/pedestrianism. He cemented that title with his victory in the First International Astley Belt Six-day Race in London, defeating seventeen others, running and walking 520.2 miles.

In 1878, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago was the undisputed world champion of ultrarunning/pedestrianism. He cemented that title with his victory in the First International Astley Belt Six-day Race in London, defeating seventeen others, running and walking 520.2 miles.

The Astley Belt quickly became the most sought-after trophy in ultrarunning. O’Leary was then the most famous runner in America and Great Britain, pushing aside the fleeting memory of Edward Payson Weston. As with any championship, want-a-be contenders came out of the woodwork. They coveted the shiny, heavy, gold and silver Astley Belt and wanted to see their own names engraved upon it. But more than anything, they also wanted the riches and the fame from adoring fans of the new endurance sport which was about to experience an explosion of popularity in both England and America.

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Challenger: William Howes

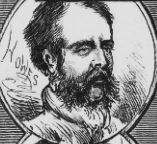

On the same day of O’Leary’s Astley Belt six-day victory, he received a challenge for the belt from William Howes (1839-), age 39, a waiter from Haggerston, England. Howes had been a very vocal critic of the Americans, O’Leary and Weston. He must have looked old because he was referred to as being “rather advanced in years.” He was 5’4” and had competed in running for many years.

Back in December 1876, O’Leary had experienced the first pedestrian defeat of his career against Howes in a 300-mile 72-hour race when O’Leary had to drop out mid-race because of sickness. Howes had accused O’Leary of faking the illness to delegitimize Howe’s victory. Then a month later, Howes anonymously tried to put together a race against O’Leary, Weston and himself. But then Howes experienced an injury, couldn’t participate, and was very mad that the race wasn’t postponed for him.

Howes Issue Challenge to O’Leary

Howes was a legitimate ultrarunner, who in February 1878 had set a new world walking record for 100 miles (18:08:20) and 24 hours (127 miles). But for unknown reasons, Howes withdrew his entry for the Astley Belt race a week before the race. Now, instead of racing against the 18 runners in that race, he wanted a head-to-head match against O’Leary to try to snatch away the coveted Astley Belt.

Howes was a legitimate ultrarunner, who in February 1878 had set a new world walking record for 100 miles (18:08:20) and 24 hours (127 miles). But for unknown reasons, Howes withdrew his entry for the Astley Belt race a week before the race. Now, instead of racing against the 18 runners in that race, he wanted a head-to-head match against O’Leary to try to snatch away the coveted Astley Belt.

O’Leary was required to accept any challenge within three months and defend the belt within 18 months, but he had no intention of staying in England with his family to race against the pesky Howes. Howes, who clearly dodged competition in the First Astley Belt Race, just one week later, on March 30, 1878, raced against ten others for 50 miles in the Agricultural Hall in London. Howes, won by two minutes and broke the world record with 7:57:54, the first to break the eight-hour barrier. (Later in the summer he would lower it further to 7:15:23 at Lillie Bridge).

Also, just three days after O’Leary’s victory, Weston, who had also pulled out of the Astley Belt race claiming illness, realizing the huge money that could be involved, issued his own challenge against O’Leary. Other challenges came from Brits, Henry Vaughan, William Corkey, and Blower Brown, all veterans of the First Astley Belt Race.

O’Leary Returns to America with the Belt

O’Leary infuriated Howes and many others in England when he made it clear that he was returning to America and that any challenge to the belt would need to be competed against him there. He said, “Having won the belt, I had the say where the walking should be done. I wouldn’t walk in London again. They don’t know where America is, and of course wouldn’t go there.” This didn’t please Sir John Astley who feared that the belt would never come back to England. He stated that if it didn’t come back, he would create an identical belt for the British to compete for, with clear rules that the competitions had to take place in England. In May 1878, after a visit to his ancestral home in Cork, Ireland, O’Leary returned to America with the Astley Belt and a reported $3,750 of winnings ($107,000 in today’s value).

O’Leary infuriated Howes and many others in England when he made it clear that he was returning to America and that any challenge to the belt would need to be competed against him there. He said, “Having won the belt, I had the say where the walking should be done. I wouldn’t walk in London again. They don’t know where America is, and of course wouldn’t go there.” This didn’t please Sir John Astley who feared that the belt would never come back to England. He stated that if it didn’t come back, he would create an identical belt for the British to compete for, with clear rules that the competitions had to take place in England. In May 1878, after a visit to his ancestral home in Cork, Ireland, O’Leary returned to America with the Astley Belt and a reported $3,750 of winnings ($107,000 in today’s value).

![]() After O’Leary’s return, John Hughes, an Irish-American from New York City issued a challenge to O’Leary for the belt. Hughes had also been a thorn in O’Leary’s side for years. As early as 1875 Hughes was issuing challenges which O’Leary rejected. Hughes had wanted to compete in the First Astley Belt Race but couldn’t raise the entrant’s fee and cover trip costs to England. Before that race, he boasted that he could have beat O’Leary if he would have had the money. O’Leary sarcastically replied, “I’ll build you a bridge to walk to London.” That bugged Hughes.

After O’Leary’s return, John Hughes, an Irish-American from New York City issued a challenge to O’Leary for the belt. Hughes had also been a thorn in O’Leary’s side for years. As early as 1875 Hughes was issuing challenges which O’Leary rejected. Hughes had wanted to compete in the First Astley Belt Race but couldn’t raise the entrant’s fee and cover trip costs to England. Before that race, he boasted that he could have beat O’Leary if he would have had the money. O’Leary sarcastically replied, “I’ll build you a bridge to walk to London.” That bugged Hughes.

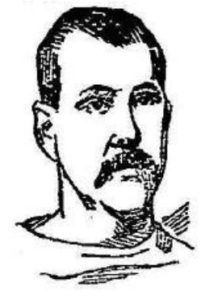

Challenger: John Hughes

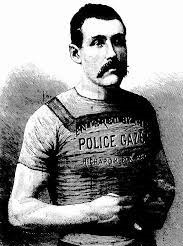

John “Lepper” Hughes (1850-1921), age 38, was a “poor day laborer” with no formal education from New York City. He was born in Roscrea, Tipperary, Ireland and was the son of a competitive runner. He was tall, 5’11” in his stocking feet, was very muscular with a dark-colored mustache, and cropped black hair. It was said, “He is stubborn as a government mule and one cannot hear him talk without believing that he will make a great pedestrian.” When he was a boy, he was a fast runner and won some races and could run close to hounds in fox hunts, and as a youth, became a champion wrestler and soccer player. He emigrated to America in 1868, became a citizen, and worked for the city of New York in Central Park.

John “Lepper” Hughes (1850-1921), age 38, was a “poor day laborer” with no formal education from New York City. He was born in Roscrea, Tipperary, Ireland and was the son of a competitive runner. He was tall, 5’11” in his stocking feet, was very muscular with a dark-colored mustache, and cropped black hair. It was said, “He is stubborn as a government mule and one cannot hear him talk without believing that he will make a great pedestrian.” When he was a boy, he was a fast runner and won some races and could run close to hounds in fox hunts, and as a youth, became a champion wrestler and soccer player. He emigrated to America in 1868, became a citizen, and worked for the city of New York in Central Park.

Hughes began his running career in 1870 and embraced the nickname of “Lepper” because of his odd jumping gait. He successfully ran in many races up to ten miles over the years and then started to do long journey walks. As Weston and O’Leary started to pile up winning money, he wanted in on the action but couldn’t find a financial backer.

Hughes Seeks to Beat O’Leary

After hearing of O’Leary’s Astley Belt victory, Hughes wanted to try to beat the 520-mile world record. In New York sporting circles, he was known as “The Greenhorn.” He made his solo attempt in April 1878 on a track of 15 laps to the mile in Central Park Garden. During the first day he had “lost his head” after being stirred by applause and ran the first 30 miles in 3:44:45. It then went downhill for the rookie ultrarunner after that. As expected, he didn’t come close to the record, but reached a respectable 408.9 miles, drinking an enormous quantity of liquor and wine along the way. When he finished, he was reported to be “pretty badly used up.”

After hearing of O’Leary’s Astley Belt victory, Hughes wanted to try to beat the 520-mile world record. In New York sporting circles, he was known as “The Greenhorn.” He made his solo attempt in April 1878 on a track of 15 laps to the mile in Central Park Garden. During the first day he had “lost his head” after being stirred by applause and ran the first 30 miles in 3:44:45. It then went downhill for the rookie ultrarunner after that. As expected, he didn’t come close to the record, but reached a respectable 408.9 miles, drinking an enormous quantity of liquor and wine along the way. When he finished, he was reported to be “pretty badly used up.”

Clearly, Hughes was under-qualified to compete for the Belt. “He does not profess to be a great walker, but he claims that he could out-run any man in the world.” He claimed to be training a very improbable 40 miles a day. “All professional pedestrians are bitterly opposed to him. They say he is a fraud and brags too much to amount to anything.”

O’Leary Forced to Accept Hughes’ Challenge

O’Leary continued to ignore Hughes’ challenges, and challenges from British runners. One complained, “O’Leary has not accepted a single challenge since he became holder of the championship belt. All those who have challenged him, he appears to think beneath his notice.” O’Leary was blunt and said, that he had no desire of shirking his responsibility to defend his championship but objected to “fourth-rate pedestrians” making money off of his reputation.

In July 1878, Sir John Astley in England, ruled that O’Leary must accept Hughes’ challenge or forfeit the Astley Belt and “Champion of the World” title. O’Leary decided to accept a challenge. Surely O’Leary knew Hughes would not be serious competition, but a defense of the Belt was needed according to the rules. Initially O’Leary made things difficult, stating that Hughes would need to cover half of the expenses and that no entrance fee would be charged to the public to watch.

Plans for the Second Astley Belt Race

In preparation for the match, in August 1878, Hughes claimed to have walked solo, 500 miles in 35 minutes less than six days at Newark, New Jersey. However, it was discovered that the track was seriously short, and he probably only walked about 300 miles.

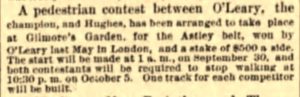

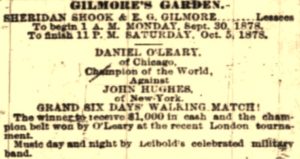

After several weeks of “somewhat acrimonious and even stormy discussions” between O’Leary and Hughes’ agents, articles of agreement were signed to race for the Second Astley Belt to be held in New York City, at Gilmore’s Garden, on September 30, 1878, with $1,000 going to the winner. “The party covering the greatest distance during the time by either running or walking without assistance is to be declared the winner.” Half of the gross proceeds of the gate money would be divided between the two, three-quarters to the winner. Sir John Astley and the Amateur Athletic Club of London would work with the athletic clubs of New York to oversee the event.

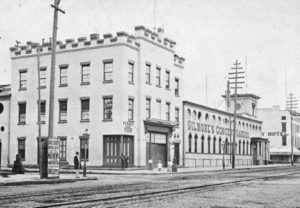

Gilmore’s Garden

Gilmore’s Garden was a venue that originally was constructed for P. T. Barnum’s Hippodrome in New York City, where the first six-day race in history was held in 1875 (see episode 95). William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) owned the property and after the circus vacated later that year, band leader Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892) leased the property for concerts, flower shows, beauty contests, dog shows, and boxing matches and renamed to Gilmore’s Concert Garden. A permanent roof was added around 1876. (Gilmore’s Garden became one of the most popular venues in the city and in May 1879, it would be renamed to Madison Square Garden and be significantly upgraded and outfitted with electric lights. The New York Life Building now stands on this historic block in New York City where so many six-day races were held.)

The Second Astley Belt Race

The Second Astley Belt Race started on September 30, 1878. It was a far cry from the celebrated, highly competitive First Astley Belt Race. This time it was like a heavy-weight boxer taking on a lightweight. Its place in ultrarunning history is truly minor, and it was only held because of the belt challenging rules. O’Leary had been training in New York City, taking daily walks from 15-40 miles at various speeds. “In regard to the match, he felt confident of not only beating Hughes, but of surpassing his own former feats and making the best time on record.” Hughes had plenty of New York friends willing to bet on him. The odds were surprisingly pretty even, in favor of O’Leary, 5-4.

The Second Astley Belt Race started on September 30, 1878. It was a far cry from the celebrated, highly competitive First Astley Belt Race. This time it was like a heavy-weight boxer taking on a lightweight. Its place in ultrarunning history is truly minor, and it was only held because of the belt challenging rules. O’Leary had been training in New York City, taking daily walks from 15-40 miles at various speeds. “In regard to the match, he felt confident of not only beating Hughes, but of surpassing his own former feats and making the best time on record.” Hughes had plenty of New York friends willing to bet on him. The odds were surprisingly pretty even, in favor of O’Leary, 5-4.

Two separate 2.5-feet wide tracks were laid down, the outer, eight laps to a mile and the inner, nine laps to a mile. O’Leary won a coin flip and chose the outer track. The surface was made of soft dirt about three inches deep rolled on top of asphalt. O’Leary would make use of a hat room where he put a comfortable cot and a cook stove. Hughes would use a little tent, also with a bed and stove. He would be helped by his wife and two children. The Garden arena included evergreens and flowering plants giving it a beautiful appearance. A grandstand used for concerts was left in place along with chairs, seats, and benches on the infield grass. Thick smoke would pour out into the building from the two stoves, filling it with a cloud, but they soon figured out how to divert it.

At the start O’Leary was given loud cheers and Hughes a few hurrahs. Off they went at 12:55 a.m. Hughes quickly repeated the same mistake he made during his solo six-day trial. He ran the first mile in 6:50, nearly four minutes faster than O’Leary. He also wore “shoes large enough for a tamed elephant.” O’Leary resisted the temptation to run and walked at a steady pace. After twelve hours, Hughes had a nine-mile lead but was paying for his fast start, suffering from a sick stomach, thought to be caused by drinking too much milk. After nearly 19 hours, Hughes reached 85 miles and retired to his tent. “He was completely used up and staggered like a drunken man. The contest was now like a race between a duke’s horse and a streetcar horse.”

At the start O’Leary was given loud cheers and Hughes a few hurrahs. Off they went at 12:55 a.m. Hughes quickly repeated the same mistake he made during his solo six-day trial. He ran the first mile in 6:50, nearly four minutes faster than O’Leary. He also wore “shoes large enough for a tamed elephant.” O’Leary resisted the temptation to run and walked at a steady pace. After twelve hours, Hughes had a nine-mile lead but was paying for his fast start, suffering from a sick stomach, thought to be caused by drinking too much milk. After nearly 19 hours, Hughes reached 85 miles and retired to his tent. “He was completely used up and staggered like a drunken man. The contest was now like a race between a duke’s horse and a streetcar horse.”

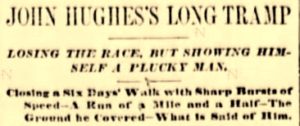

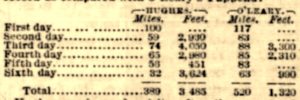

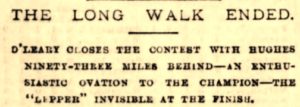

O’Leary reached 100 miles in 21:39:55 and 103 miles for the first day. He continued to increase the lead each day and Hughes hung in there to the end. Clearly, O’Leary didn’t push for a first-class effort. Thousands came to watch the final day, but the final score was disappointing for an Astley Belt race: O’Leary 403 miles to Hughes with 310 miles. O’Leary said afterwards, “Had I had a better competitor, I could have made more miles, but from the start, I was convinced it was a walk-over. I wish that the only man who ever put me to the top of my speed, Vaughan, of London, had been here, then I could have shown what is possible for me to accomplish.”

O’Leary reached 100 miles in 21:39:55 and 103 miles for the first day. He continued to increase the lead each day and Hughes hung in there to the end. Clearly, O’Leary didn’t push for a first-class effort. Thousands came to watch the final day, but the final score was disappointing for an Astley Belt race: O’Leary 403 miles to Hughes with 310 miles. O’Leary said afterwards, “Had I had a better competitor, I could have made more miles, but from the start, I was convinced it was a walk-over. I wish that the only man who ever put me to the top of my speed, Vaughan, of London, had been here, then I could have shown what is possible for me to accomplish.”

A day later, O’Leary said that Hughes was a “humbug” and criticized Sir John Astley for forcing him to compete against him. Critics said, “Hughes never displayed the slightest characteristics of a walker and slouched around the track with a shambling gait that did not even have the merit of covering the ground fast. The spectators saw in him a worn out and exhausted man who had struggled hard to win a fight in which he was overmatched.”

Yes, the Second Astley Belt Race for the Championship of the World was a mess, and an embarrassment. In England, the championship was called a fraud in the sport. “The distance covered was by no means long enough. If this is the best specimen of American mixture that can be produced, the sooner these contests die out the better.”

But the event was a financial windfall for O’Leary and his friends. For his effort he won an engraved gold medal and $5,000 (valued at $143,000 today). Hughes was awarded about $2,000. A few days later, Hughes pressed charges to have his three backers arrested. He believed that they had poisoned his milk and attempted to swindle him out of all his prize money. He was illiterate and had been tricked into making his mark on a power-of-attorney document, giving his backers the authority to get his money. (Hughes would become a very elite six-day runner. In 1881, Hughes he broke the six-day world record with 568 miles winning $90,000 in today’s value).

But the event was a financial windfall for O’Leary and his friends. For his effort he won an engraved gold medal and $5,000 (valued at $143,000 today). Hughes was awarded about $2,000. A few days later, Hughes pressed charges to have his three backers arrested. He believed that they had poisoned his milk and attempted to swindle him out of all his prize money. He was illiterate and had been tricked into making his mark on a power-of-attorney document, giving his backers the authority to get his money. (Hughes would become a very elite six-day runner. In 1881, Hughes he broke the six-day world record with 568 miles winning $90,000 in today’s value).

Challenges were immediately issued to O’Leary for the belt by other Americans, including Charles Harriman of Boston, and John Ennis of Chicago. O’Leary, learning from his mistake of wasting effort walking against inferiors replied, “I will melt the belt before I will compete against any man that has not a record of 500 miles in six days.”

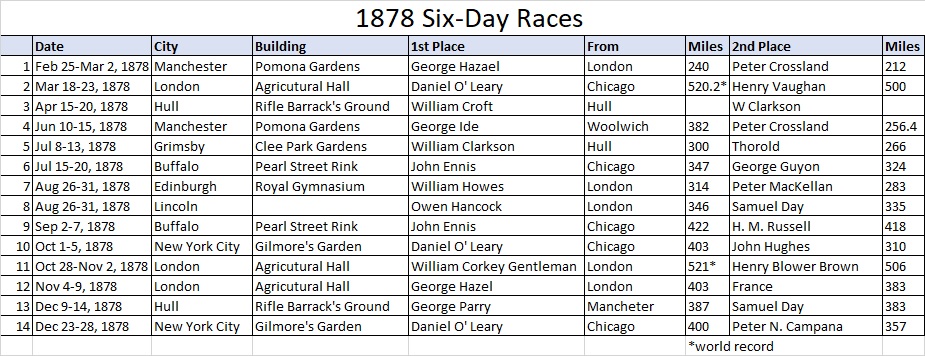

Other 1878 Six-Day Races

Other Six-Day races were conducted during 1878 in England where they were now more popular than in America. But most of the races were competed at a lower tier competitively, with no runners going over 400 miles. One race of note was held with 24 starters at the Pomona Gardens in Manchester. But the race limited the runners to 14 hours per day and the winner, George Ide, only reached 382 miles. In America, two six-day races were held at the Pearl Street Rink in Buffalo, New York, a city that had enthusiastically embraced Pedestrianism. John Ennis of Chicago won a match there with 422 miles.

English Astley Belt Race

Sir John Astley wasn’t happy that his belt was still in America and that he could not use it yet for another prominent six-day race in England. He had lost total control of the race series that he had founded. He announced that he would hold a race in late October for a separate Astley Challenge Belt, for the “Long Distance Championship of England.” O’Leary was still the world champion and felt no compelling reason to compete in the British race. He said he already had a belt and did not need two. He still insisted that the next International Astley Belt Race be held in America at some future date. The rules stated that he did not need to defend it again that year, so he at first intended to take a well-deserved break and enjoy his fortune.

Sir John Astley wasn’t happy that his belt was still in America and that he could not use it yet for another prominent six-day race in England. He had lost total control of the race series that he had founded. He announced that he would hold a race in late October for a separate Astley Challenge Belt, for the “Long Distance Championship of England.” O’Leary was still the world champion and felt no compelling reason to compete in the British race. He said he already had a belt and did not need two. He still insisted that the next International Astley Belt Race be held in America at some future date. The rules stated that he did not need to defend it again that year, so he at first intended to take a well-deserved break and enjoy his fortune.

Plans for the English Astley Belt Race

The Championship of England race would be held in the Agricultural Hall in London. Rules and conditions for the race were nearly identical to the First Astley Belt Race with a few important exceptions. There would only be one track, not a separate one for Weston. “All will walk on one wide track, and any competitor may turn and go in the opposite direction at the completion of any mile.” Sleeping accommodations would be greatly improved. All races for this new challenge belt had to be held in London, which countered the problem that O’Leary was causing by insisting his challenges take place in America.

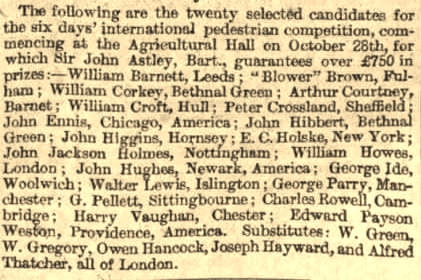

Interest in the new race was very strong, with 24 entries in just a month. Without O’Leary in the race lineup, Edward Payson Weston entered the event. Weston had been in England for nearly three years. Because of his very lavish lifestyle, living in posh hotels, he had squandered away all his winnings of hundreds of thousands of dollars in today’s value, and declared bankruptcy in the British courts. He claimed debts of $5,200 ($144,000 in today’s value!). Weston needed some more wins. Twenty-three entrants were selected including two other Americans, John Ennis, and W. H. Richardson

Interest in the new race was very strong, with 24 entries in just a month. Without O’Leary in the race lineup, Edward Payson Weston entered the event. Weston had been in England for nearly three years. Because of his very lavish lifestyle, living in posh hotels, he had squandered away all his winnings of hundreds of thousands of dollars in today’s value, and declared bankruptcy in the British courts. He claimed debts of $5,200 ($144,000 in today’s value!). Weston needed some more wins. Twenty-three entrants were selected including two other Americans, John Ennis, and W. H. Richardson

Not all were in favor of the event. “We are to be again treated to more disgusting sights. Such exhibition ought to be prohibited by law. They are a disgrace to humanity, reducing it to the state of a beast, with the look of a wild animal tramping wretchedly round and round a gloomy enclosure for the edification of an ignorant and gaping crowd. The quantity of harm wreaked by foolish enthusiasts like Sir John Astley, who pretend to a love of sport, and know nothing whatsoever of the mechanism or uses of the human body, is incalculable.”

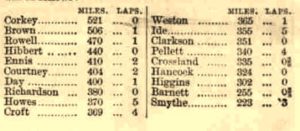

The Start

The race started at 1:05 a.m. on October 28, 1878 with 23 starters. Sir John Astley gave a speech and then ordered the men to start. Blower Brown (see bio in episode 106) quickly went into the lead clocking the first mile in a speedy 7:43 and reached 50 miles first, in 8:01:47. Most contestants ran and surprisingly, even Weston ran at times, “it being a series of short steps.” Weston refused to use the plain tent provided and would leave the hall to sleep in more luxurious accommodations. The race was highly competitive that evening in front of 8,000 spectators. After the first day the score was Peter Crossland 117 miles, William “Corkey” Gentleman 114, and Blower Brown 111. Weston was in 6th place with 101 miles. Eight of the 23 three starters reached 100 miles on day one, a significant improvement for British ultrarunners. After 48 hours the top three were Corkey (see bio in episode 106) with 204 miles, Brown and Crossland with 200. Vaughan, the favorite, wasn’t doing well because he had sprained an ankle during training when a dog had run in front of him and quit the race after two days.

The Finish

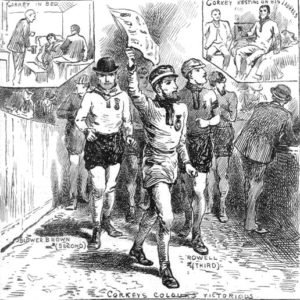

By end of the fifth day, it was a two-man race between Corkey with 457 miles and Brown with 450. Weston was far behind in fifth with 365 miles and quit the race. He was suffering from a sprained foot. On the last day, when Brown left the track for a Turkish bath, Corkey extended his lead to nearly 20 miles. The spectator attendance was enormous, estimated at 15,000 people. Corkey pushed ahead strongly and was ahead of O’Leary’s world record pace. He reached 500 miles in a world record time of 132:50:00.

By end of the fifth day, it was a two-man race between Corkey with 457 miles and Brown with 450. Weston was far behind in fifth with 365 miles and quit the race. He was suffering from a sprained foot. On the last day, when Brown left the track for a Turkish bath, Corkey extended his lead to nearly 20 miles. The spectator attendance was enormous, estimated at 15,000 people. Corkey pushed ahead strongly and was ahead of O’Leary’s world record pace. He reached 500 miles in a world record time of 132:50:00.

At a little after 7 p.m., Corkey reached the world record of 520 miles and two laps in a time of about an hour faster than O’Leary’s record time. After a short rest, he again appeared on the track, clad in a silk costume provided by Astley, bearing the Union Jack, arm-in-arm with Mrs. Corkey wearing a gaudy bonnet also provided by Astley. The band played “See the Conquering Hero” and the race ended at 8:20 p.m. by mutual consent of the remaining runners, after Corkey reached a new world record of 521 miles. The final score was Corkey 521, Brown 506, and Rowell 470.

At a little after 7 p.m., Corkey reached the world record of 520 miles and two laps in a time of about an hour faster than O’Leary’s record time. After a short rest, he again appeared on the track, clad in a silk costume provided by Astley, bearing the Union Jack, arm-in-arm with Mrs. Corkey wearing a gaudy bonnet also provided by Astley. The band played “See the Conquering Hero” and the race ended at 8:20 p.m. by mutual consent of the remaining runners, after Corkey reached a new world record of 521 miles. The final score was Corkey 521, Brown 506, and Rowell 470.

Corkey immediately issued a challenge to race O’Leary for the Astley Belt and said he would even pay for O’Leary’s expenses to travel to England for the match. Brown also issued his challenge and was willing to race in America.

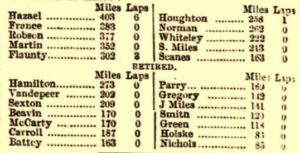

Secondary English Six-Day Race

Because the six-day race was so popular among the British, the next day on November 5, 1878, Astley conducted another six-day race in the Agricultural Hall for an additional group of 20 runners who didn’t make the cut for the first race. George Hazael (see bio in episode 106), the 50-mile (7:15:23) and 100-mile (18:08:20) world record holder, was the favorite and took the lead from that start. On the first day he lowered his 100-mile world record to 17:03:00.

Because the six-day race was so popular among the British, the next day on November 5, 1878, Astley conducted another six-day race in the Agricultural Hall for an additional group of 20 runners who didn’t make the cut for the first race. George Hazael (see bio in episode 106), the 50-mile (7:15:23) and 100-mile (18:08:20) world record holder, was the favorite and took the lead from that start. On the first day he lowered his 100-mile world record to 17:03:00.

The organizers were disappointed that this second group did not perform as well as the first group. On the last day, the race only continued to attract spectators and their money. “Several of the competitors who had been announced as retired from the contest, put in posthumous appearances just for the sake of keeping up a semblance of interest in the proceedings. By evening, scarcely any of the public patronized the affair with the greatest number at any one time 800.” In the end, Hazael won by 20 miles with 403 miles. The contest was viewed as a failure. “The promoters must regret that they ever started so foolish a venture, one that likely imperiled the future of their newly popular hobby of ‘go as you please’ long distance competitions.”

The organizers were disappointed that this second group did not perform as well as the first group. On the last day, the race only continued to attract spectators and their money. “Several of the competitors who had been announced as retired from the contest, put in posthumous appearances just for the sake of keeping up a semblance of interest in the proceedings. By evening, scarcely any of the public patronized the affair with the greatest number at any one time 800.” In the end, Hazael won by 20 miles with 403 miles. The contest was viewed as a failure. “The promoters must regret that they ever started so foolish a venture, one that likely imperiled the future of their newly popular hobby of ‘go as you please’ long distance competitions.”

In all, at least 14 six-day races were held during 1878 in both Great Britain and America. To close off the year, O’Leary raced Peter Napoleon Campana for six days at Gilmore’s Garden in New York City. The story of Campana is another lesson to be weary of over-anxious ultrarunners seeking fame and fortune.

Peter Napoleon Campana

Peter Napoleon Campana (1836-1906), age 42, was a fireman from Bridgeport, Connecticut. His family came from France. As a youth he was very involved in athletics and received the nickname of “Young Sport.” While living in New York, he became a volunteer fireman and later when he moved to Connecticut was a peddler of nuts and fruit. Running fast was a passion and an extraordinary talent. By 1860 he was competing in races up to ten miles and was winning.

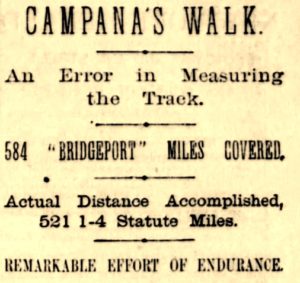

Campana Claims to Break the Six-Day World Record

Campana wanted to become a professional pedestrian. On November 11, 1878, he was determined to try to beat O’Leary’s six-day world record of 520 miles in a solo attempt. He made his solo attempt at Hubbell’s Hall in Bridgeport on a cramped slippery track, 14 laps to a mile. He started impressively, reaching 100 miles in 17:53:00.

Campana wanted to become a professional pedestrian. On November 11, 1878, he was determined to try to beat O’Leary’s six-day world record of 520 miles in a solo attempt. He made his solo attempt at Hubbell’s Hall in Bridgeport on a cramped slippery track, 14 laps to a mile. He started impressively, reaching 100 miles in 17:53:00.

Campana reached the world record 521 miles with more than ten hours spare, or did he? There was one huge problem. During his effort, the track was remeasured and found to be 15.625 laps to the mile instead of 14. Campana was actually at about 466 miles. He tried to make up the missing miles and indeed claimed to reach 521.25 miles for a confusing new six-day world record with some creative math and likely poor lap counting. It was joked that he covered 584 “Bridgeport miles.” The performance was deemed “not sufficiently authenticated to entitle him to a record.” Campana was confident that he had broken the record and was willing to prove his abilities against the best. He became an instant celebrity in Bridgeport and quickly divorced his wife and found a new wife to marry.

Campana reached the world record 521 miles with more than ten hours spare, or did he? There was one huge problem. During his effort, the track was remeasured and found to be 15.625 laps to the mile instead of 14. Campana was actually at about 466 miles. He tried to make up the missing miles and indeed claimed to reach 521.25 miles for a confusing new six-day world record with some creative math and likely poor lap counting. It was joked that he covered 584 “Bridgeport miles.” The performance was deemed “not sufficiently authenticated to entitle him to a record.” Campana was confident that he had broken the record and was willing to prove his abilities against the best. He became an instant celebrity in Bridgeport and quickly divorced his wife and found a new wife to marry.

O’Leary vs. Campana

Campana’s six-day accomplishment, whether true or not, received a lot of publicity and was noticed by O’Leary. He wasn’t happy learning that his six-day world record had been surpassed by an unknown amateur. Within a week of Campana’s accomplishment, O’Leary sought out a head-to-head match with Campana to prove that he could beat him. The New York press wasn’t convinced and wrote, “Peter Napolean Campana can no doubt easily beat O’Leary.” Campana accepted the challenge. The two met for the first time in mid-December 1878 to sign the articles of agreement and O’Leary said, “I like the looks of the man, and he may surprise all of us.”

Campana’s six-day accomplishment, whether true or not, received a lot of publicity and was noticed by O’Leary. He wasn’t happy learning that his six-day world record had been surpassed by an unknown amateur. Within a week of Campana’s accomplishment, O’Leary sought out a head-to-head match with Campana to prove that he could beat him. The New York press wasn’t convinced and wrote, “Peter Napolean Campana can no doubt easily beat O’Leary.” Campana accepted the challenge. The two met for the first time in mid-December 1878 to sign the articles of agreement and O’Leary said, “I like the looks of the man, and he may surprise all of us.”

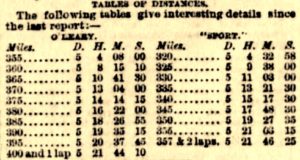

The race began on December 23, 1878, at Gilmore’s Garden in New York City under the direction of William B. Curtis. It was held with the same “go-as-you-please” rules established by Astley. Two separate tracks were used, nine laps to a mile and eight laps to a mile. They were the same tracks used in the recent Second Astley Belt Race. O’Leary set up his same sleeping quarters and used his same trainers as in the former race.

The Start

The race began at 1 a.m. “A stillness reigned in the vast building, which was only broken at intervals by the voice of the timekeeper as he recorded in a loud voice the number of laps, the miles, and the time of each competitor.” Campana wore a shirt with the word “Sport” written on the front. Both occasionally broke out into a run.

Of Campana it was written, “He is about five feet eight inches high, very muscular, and broad across the shoulders with a small waist. He has a very slouching gait, not so bad as Hughes, but without any of the style or grace of O’Leary. His most natural gait is a little dogtrot about five to six miles an hour, and this is his favorite method of getting along.”

After ten hours Campana had built up an eight-mile lead due to O’Leary taking a two-hour break early on. After the first day, Campana held a surprising lead, 90 miles to 83 for O’Leary.

Running in Smoke

The race continued during the week and even entertained Christmas Day spectators. A New York Times reporter couldn’t understand the fascination. “Thousands who, despite the manifold discomforts to which they were subjected, found a mysterious fascination in the place that compelled them to linger hour after hour, gazing at the contestants and yelling themselves hoarse over the mediocre exhibition to which they were treated. The clouds of dust and tobacco smoke that were so dense that from one end of the building the other was invisible, made an atmosphere that was terrible to breathe, and proved very distressing to the pedestrians.”

Campana Crumbles

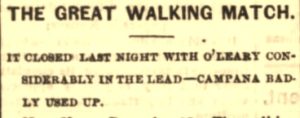

New York had hoped to witness an impressive high-milage walking match after the disappointing Second Astley Belt match between O’Leary and Hughes. But again, they were greatly disappointed, and it was referred to as a farce. By day five, Campana wasn’t doing well with a terribly swollen knee. “The poor fellow presented a pitiable sight as he shuffled around the track, staggering as he walked, having a man on either side, apparently ready to catch him if he should fall.” At times the crowd taunted him, provoking him to strike a spectator. Some in the crowd shouted that the event should be stopped. O’Leary suffered from the foul dusty and smoky air in the building. After four days, the score was O’Leary 290 miles, Campana 260. After five days, O’Leary extended the lead to 24 miles.

New York had hoped to witness an impressive high-milage walking match after the disappointing Second Astley Belt match between O’Leary and Hughes. But again, they were greatly disappointed, and it was referred to as a farce. By day five, Campana wasn’t doing well with a terribly swollen knee. “The poor fellow presented a pitiable sight as he shuffled around the track, staggering as he walked, having a man on either side, apparently ready to catch him if he should fall.” At times the crowd taunted him, provoking him to strike a spectator. Some in the crowd shouted that the event should be stopped. O’Leary suffered from the foul dusty and smoky air in the building. After four days, the score was O’Leary 290 miles, Campana 260. After five days, O’Leary extended the lead to 24 miles.

Campana was a mess on the last day. “Livid rings were under the eyes and great seams that seemed conduits of woe and weariness ran downward past the corners of his mouth. His left foot was turned outward at precise right-angles with the right one, and every time he swung it forward, he used his hand for its assistance. Shouts of “Old Stag” and “Old Sport” instead of “Young Sport” were yelled at him so often that they seemed like guns at a funeral.” O’Leary suffered from terrible blisters on his feet and didn’t dare take off his shoes for fear he wouldn’t be able to put them back on. He was greeted by cheer after cheer. Both were accused of using excessive liquor that last day as a stimulant. In the end, O’Leary reached only 400 miles to Campana’s 357 miles.

Campana was a mess on the last day. “Livid rings were under the eyes and great seams that seemed conduits of woe and weariness ran downward past the corners of his mouth. His left foot was turned outward at precise right-angles with the right one, and every time he swung it forward, he used his hand for its assistance. Shouts of “Old Stag” and “Old Sport” instead of “Young Sport” were yelled at him so often that they seemed like guns at a funeral.” O’Leary suffered from terrible blisters on his feet and didn’t dare take off his shoes for fear he wouldn’t be able to put them back on. He was greeted by cheer after cheer. Both were accused of using excessive liquor that last day as a stimulant. In the end, O’Leary reached only 400 miles to Campana’s 357 miles.

O’Leary declared a day later, “It was the poorest six days’ walk that I have ever made. I do not think that I shall walk much more. I shall retire from the track after the next match for the Astley Belt.” When asked about Campana he commented that he was a wonderful plucky man who was attended to poorly for the first two days of the walk. A doctor had too tightly wrapped his leg. “I have a great respect for him. He must have suffered intensely.” O’Leary was rumored to have received $12,000 from the race, valued at $333,000 today. Campana was on his feet the next day, recovering well, and hoped to compete in the next Astley Belt Race.

Campana’s Downfall

![]() A week later, William Caufield revealed that Campana’s “world record” in November at Bridgeport, Connecticut had been cheated. Caufield was a timer in the event and admitted that he had credited Campana an extra 20 miles every morning and ran ten miles for him each night while Campana was sleeping. A second witness signed an affidavit that ten extra miles were given to Campana on the last day to help him reach 521.25 miles before time ran out. Campana would have had to know about this huge discrepancy. He never denied the charge, continued the fraud, and started to call himself, “champion long-distance runner and walker of the world.” O’Leary would have never run against him if he had known that he was a fraud and pretender.

A week later, William Caufield revealed that Campana’s “world record” in November at Bridgeport, Connecticut had been cheated. Caufield was a timer in the event and admitted that he had credited Campana an extra 20 miles every morning and ran ten miles for him each night while Campana was sleeping. A second witness signed an affidavit that ten extra miles were given to Campana on the last day to help him reach 521.25 miles before time ran out. Campana would have had to know about this huge discrepancy. He never denied the charge, continued the fraud, and started to call himself, “champion long-distance runner and walker of the world.” O’Leary would have never run against him if he had known that he was a fraud and pretender.

![]() The press was not kind to Campana. “Campana proved an utter failure as a long-distance walker, and was of course, like all of his kind, ready with excuses for not having done what he promised. The truth is, that he is an old, played-out man, whose days for tremendous exertions have long since passed.”

The press was not kind to Campana. “Campana proved an utter failure as a long-distance walker, and was of course, like all of his kind, ready with excuses for not having done what he promised. The truth is, that he is an old, played-out man, whose days for tremendous exertions have long since passed.”

Another article summed up the two disappointing six-day races held at Gilmore’s Garden, “When someone has made a great hit in a particular line of public entertainment, crowds of frauds and pretenders are sure to foist themselves on the public, in the hope of raking in heaps of shekels. Pedestrianism is no exception to this rule. Hughes and Campana – Frauds! Frauds! Frauds! Forced themselves before a long-suffering public.”

English papers called the O’Leary-Campana race “a wobble.” The New York press said the effort was “an absurd performance and was a disreputable fraud on the public.”

Campana received about $4,000 ($115,000 in today’s value) from the race against O’Leary. Within a couple weeks, he bought a house and furnished it luxuriously. Within days of moving in, his new wife pressed charges against Campana for beating and choking her. He was arrested for assault and battery and the two separated but later reconciled. There was more to Campana than people realized, however he went on to compete again in many six-day races, never won, spent time in and out jail many times, and was penniless a few years later. In his early 50s he was viewed as old man and brought out as a funny clown attraction during races although he could still exceed 300 miles. People believed he was 20 years older. In 1890 while imprisoned at a workhouse, he lost all his fingers on one hand in a machine accident. He became a peddler of gum outside of theaters and died penniless at the age of 70. Beware of the fraudulent ultrarunner.

Campana received about $4,000 ($115,000 in today’s value) from the race against O’Leary. Within a couple weeks, he bought a house and furnished it luxuriously. Within days of moving in, his new wife pressed charges against Campana for beating and choking her. He was arrested for assault and battery and the two separated but later reconciled. There was more to Campana than people realized, however he went on to compete again in many six-day races, never won, spent time in and out jail many times, and was penniless a few years later. In his early 50s he was viewed as old man and brought out as a funny clown attraction during races although he could still exceed 300 miles. People believed he was 20 years older. In 1890 while imprisoned at a workhouse, he lost all his fingers on one hand in a machine accident. He became a peddler of gum outside of theaters and died penniless at the age of 70. Beware of the fraudulent ultrarunner.

Six-Day Bicycle Race

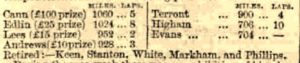

On November 18, 1878, the first six-day bicycle race in history was started at the Agricultural Hall in London for £100 pounds if the winning rider reached 1,000 miles. Among the competitors was the famous cyclist David Stanton (1844-1907), who was featured during the 1876 Grand Walking Tournament in Chicago (see episode 104).

The riders were restricted to ride 18 hours per day, when there were spectators present, and rode on a wooden track of boards, 7.5 laps to a mile. William Cann of Sheffield won the event on a high wheeler with a record 1,060 miles, 35 miles ahead of the next rider. The event was described as very exciting, with good attendance by spectators who witnessed some crashes. The track was defined poorly with a paint line and riders frequently cut corners. “We are left in a state of doubt as to the actual distance accomplished and thus the record is rendered practically worthless.”

Soon other six-day race firsts appeared in 1879 including swimming (75 miles), horse racing (557 miles), roller skating (644 miles), and even wheelbarrow pushing (310 miles).

This bicycle event was significant because some pedestrian historians believe these bicycle races eventually led to the lack of interest in the six-day running races and its downfall. However, that is an oversimplification of the eventual downfall of the six-day race. There were other far more impactful reasons for its demise that will be covered later. In the meantime, the glory days were still ahead.

Stay tuned for the truly amazing Third Astley Belt Race.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Michael O’Dwyer, “John Hughes”

- P. S. Marshall, “Napoleon Campana – Old Sport”

- “Six Day Cycle Race”

- The Bury and Norwich Post (England), Apr 2, 1878

- Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (England), Mar 26, 1878

- Manchester Evening News (England), Mar 27, Oct 12, 23, 1878

- The Sportsman (London, England), Apr 3, 1878

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 5, Nov 23, 1878

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Apr 27, 1878

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Apr 28, 1878

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Apr 29, 1878

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Mar 17, Oct 8, Nov 8, 1878

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 16, May 3, 23, Jul 25, Aug 11, Sep 29-30, 1878

- Sporting Life (London, England), Jul 24, Aug 31, 1878

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Aug 26, 1878, Jan 8, 1879

- Time Union (Brooklyn, New York), Sep 12, 1878

- Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), Sep 12, 1878

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Sep 12, Oct 1,6, Nov 17, 20. Dec 15, 30, 1878

- The Sun (New York, New York), Sep 30, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Sep 30, 1878

- Weekly Dispatch (London, England), Oct 13, 1878

- The Globe (London, England), Oct 28, 1878

- London Evening Standard (England), Oct 28, Nov 2-4, 1878

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Oct 30, 1878

- Penny Illustrated Paper (London, England), Nov 9, 1878

- The Yorkshire Herald (York, England), Nov 5-11, 1878

- Illustrated Police News (London, England), Nov 23, 1878

- The Referee (London, England), Nov 24, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 9, 29, 1878

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 24, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 27, 1878, Jan 26, 1879

- Lancaster Times (New York), Jan 23, 1879