Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:20 — 31.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Recently, the six-day race received some attention in ultrarunning news because the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) announced that they would no longer recognize the six-day event or keep records for it. This shocked many ultrarunning historians and particularly runners who participate in multi-day fixed-time races. After a brief uproar, the new IAU leadership back-peddled, somewhat admitted to their ignorance about six-day ultrarunning history and agreed to continue to recognize the event that has roots in the sport going back nearly 250 years.

Recently, the six-day race received some attention in ultrarunning news because the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) announced that they would no longer recognize the six-day event or keep records for it. This shocked many ultrarunning historians and particularly runners who participate in multi-day fixed-time races. After a brief uproar, the new IAU leadership back-peddled, somewhat admitted to their ignorance about six-day ultrarunning history and agreed to continue to recognize the event that has roots in the sport going back nearly 250 years.

Ultrarunners who exclusively run trails may wonder, “what is this six-day race and why is it important?” The six-day race is an event to see how far you can run or walk in a period of 144 hours or six days on roads, tracks, or trails. Six days was a historic time limit established to avoid competing on Sundays, respecting local laws of the time and the religious beliefs of many of the participants.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast and website. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

Six-Day Background

Historically, the six-day race grew out of solo six-day challenges, motivated by significant wagers and fame. They were first accomplished by ultra-distance walker/runners referred to as “pedestrians” who covering staggering distances during the late 1700s. Recent research has discovered that there were far more athletes than previously known, who took up the six-day challenge in the early 1800s. These occurred exclusively in Britain. Their grueling runs/walks were accomplished outdoors on dirt and muddy roads/trails, frequently in harsh weather conditions.

How did the six-day challenge begin? Here is the story.

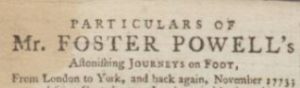

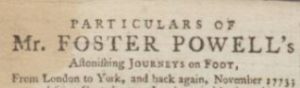

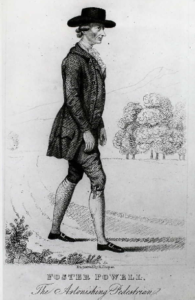

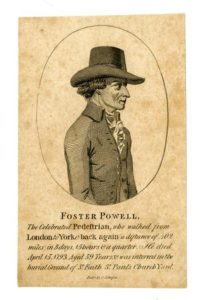

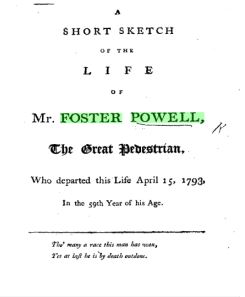

Foster Powell, the Father of the Six-Day Race

![]()

![]()

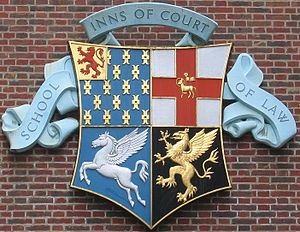

When Foster Powell was 28, in 1762, he moved to London to work as a law clerk for a “temple lawyer” at an inn. There were a group of inns in London called the “Inns of Court” attached to Churches, used as offices for clerks and lawyers. These inns consisted of sections called the Inner Temple and Middle Temple. In 1766, Powel moved, and went to work for his uncle at New Inn (next to Clements Inn), another inn for clerks and lawyers. He worked and lived there for the rest of his life.

Powell worked hard but was the object of ridicule by his fellow clerks who regarded him as “a milksop and a muff.” He was described as “a cadaverous-looking young fellow, thin and apparently weak. He was thought very little of, either in respect of his mental or physical qualities.” He was “a quiet inoffensive lad, shy, and somewhat unsocial, with nothing in the faintest degree remarkable in him.” His truly remarkable talent soon became evident as he became fond to taking long, solitary walks.

One Saturday, Powell was asked by his fellow clerks where he was going to spend Sunday. He replied that he intended to walk to Windsor and back (about 50 miles) starting after work. “This announcement provoked the jeers of his companions, thereupon for the moment he lost his temper and challenged any one of them to walk with him.” He wasn’t actually serious about going that distance, but once two other clerks agreed to walk, he couldn’t back down. Off they went and the first companion dropped out after ten miles and the second after twenty. Powell finished alone. “This feat raised him immensely in the estimation of fellow clerks, who spread the reports of his pedestrian prowess.”

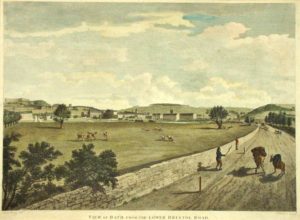

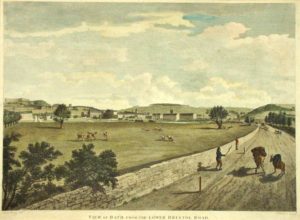

Powell’s first widely publicized walk was for 50 miles on the famed Bath Road to London, the future site of many 100-mile world running records in the 1900s. He covered the 50 miles in seven hours, wearing “a greatcoat and leather breeches” and won 20 guineas. “Walking” in those very early days was a general term. These pioneer pedestrians of the late 1700s and early 1800s, actually performed a “jog-trot,” or a mixture of walking and running. There was no emphasis yet on “fair heel-toe” walking.

As Powell excelled, his walking became an additional source for him to earn money — through wagers. In 1767 he walked through France and Switzerland, astonishing the French by walking 200 miles in three days. Returning to England he was challenged to a 40-mile race against Richard West, which stirred up great interest. About 1,000 people came to watch as the two men constantly exchanged the lead. Powell lost by only 100 paces.

Powell’s First Six-Day Run

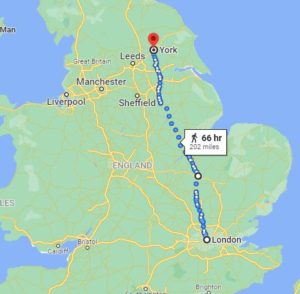

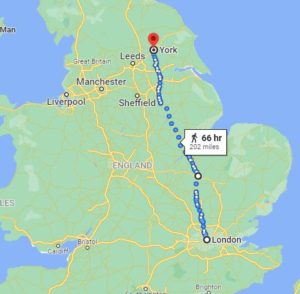

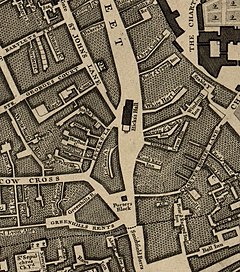

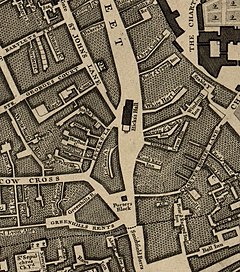

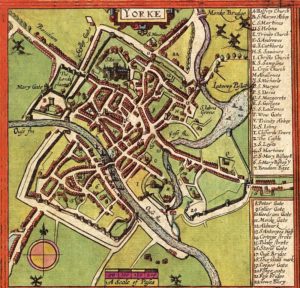

But the event that caused the greatest stir was his attempt to walk/run about 400 miles from London to York and back in less than six days. About 1635, Richard Norwood, a North American surveyor, carefully measured the distance between the two cities using a Gunter’s chain and pacing, taking into careful account the turns and hills, resulting in a 200-mile route.

Powell chose the London to York route because it was chosen a well authenticated distance. “Public opinion was divided as to the possibility of the feat. Many good judges holding that except under very favorable conditions of weather, the thing was absolutely impossible.” Heavy betting took place with the odds being slightly in favor of Powell.

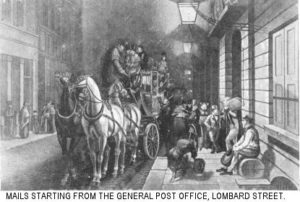

At age 34, Powell started his historic six-day journey on November 29, 1773, at 12:20 a.m. He started from Hick’s Hall, located in London at the end of today’s St. John Street. This old courthouse hall had been built in 1612 and had been used for more than 160 years the hear cases in the county of Middlesex. It was located at the start of what was called “The Great North Road” that ran between London and York, continuing on to Edinburgh, Scotland. Stagecoaches traveled this dirt road daily, delivering mail to the cities. The daily mail took 21 hours to go from London to York.

Powell was determined to succeed, and covered an impressive 88 miles on the first day in 20.5 hours, reaching Stamford where he stopped for the night at 9 p.m. On day two he reached Doncaster with its great church-tower and smoking chimney-stalks for another 72 miles in about 12 hours.

Because of a chronic pain in his side, Powell wore a strengthening wrap for the entire journey. His appetite was poor, and he fueled nearly entirely along the way on toast, tea, water, and some beer. He waved to the mail coaches that passed him daily in each direction. The coach, wagon, and cart traffic had worn deep ruts in the road which was a difficult obstacle for him to run over. “Coaches and carts took liberty to pick their best advantages and utterly confounded the road in all wide places, so that it was not only unpleasurable, but extremely perplexing and cumbersome both to themselves and to all travelers.” Another obstacle was the numerous hills along the way. However, it was said, “the rises called ‘hills’ on the Great North Road would generally pass unnoticed elsewhere.”

Did Powell only walk, or did he run too? Yes, he also ran. Some sportsmen rode out from York, 20 miles to meet him heading that way. “They found him cheerful and confident, and to show how fresh he was, he volunteered to run the last 17 miles, which he did in less than two hours.” For the last three miles that day several people tried to run with him but could not keep up with the incredible athlete.

On day three, Powell reached York, and entered the ancient city section, with the grim castle in front, bridges to the left and then came to the walled city through Micklegate, the finest of all the medieval defensible gateways. There, he reached the turnaround point, 200 miles.

At Highgate in north London, with four miles to go, he was met by a crowd of 5,000 people who escorted, him to the finish while some played French horns. He had covered the remaining 56 miles that day, and reached Hick’s Hall in the evening at 6:30 p.m. He believed that in total, he had covered 394 miles, although it likely measured more than 400 miles if he covered all the distance on foot. His finish time was five days, 18 hours, 10 minutes. His nightly rest stops totaled 34.5 hours over the six days.

News of his accomplishment spread across London. Other sports of the era also took note of this amazing six-day feat. A few months after Powell’s walk, it was pointed out that in May 1606, John Leyton, a groom for King James, took a wager to ride between London and York 200 miles each day for six days on a relay of horses. He rode 16 hours each day, averaging about 12 miles per hour. His motivation was “to the greater praise of his strength in acting, than to his discretion in undertaking it.” A couple decades later, when King Charles the first was at York, it was a frequent occurrence for couriers to ride with dispatches between London and York, completing the double journey in 34 hours.

Powell’s Second Six-Day Run

In 1788, Powell repeated the London-York and back feat, again in six days. He made his start and finish again on St. John Street at the site of the recently demolished, “Old Hick’s Hall.” He was accompanied by two men on horseback and one on foot. This time his six-day challenge attracted a huge number of spectators all along the route. It was reported, “The streets of several towns he went through, and even the roads for several miles, were crowded with both horse and foot, as almost to impede his passage.”

Powell’s Third Six-Day Run

In 1790 he attempted the run for the third time, and finished in five days, 22 hours, ten minutes. “He was so fresh that he offered to walk 100 miles the next day in 24 hours.”

Powell’s Fourth Six-Day Run

In July 1792, Powell, age 58, finally improved his fastest-known-time on the Great North Road by covering the 400+ miles in only five days, 13 hours, 35 minutes, proving his was the greatest pedestrian of his time. During this challenge, he slept for only five hours each night. The roads were very muddy and the water was “so boisterous, that it was only with superhuman exertions that he pulled off his match.” Elated with his success, Powell wanted to walk 500 miles in seven days but could not find anyone to accept the wager.

Foster Powell’s Death and Legacy

Others Try to Beat Powell

Foster Powell had set the six-day standard that would be remembered for decades, although his fastest known time was at times confused because his most famous run was the first one. Nearly all six-day attempts in the decades that followed, pointed their efforts to Powell’s previous accomplishments. Dozens attempted to match or improve on his feat. Each attempt had their own unique experiences that are interesting to examine and will be familiar to those who participate in fixed-time races today.

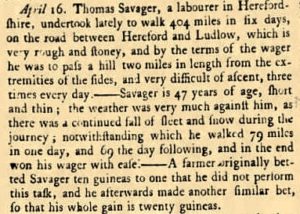

Thomas Savager – 1789

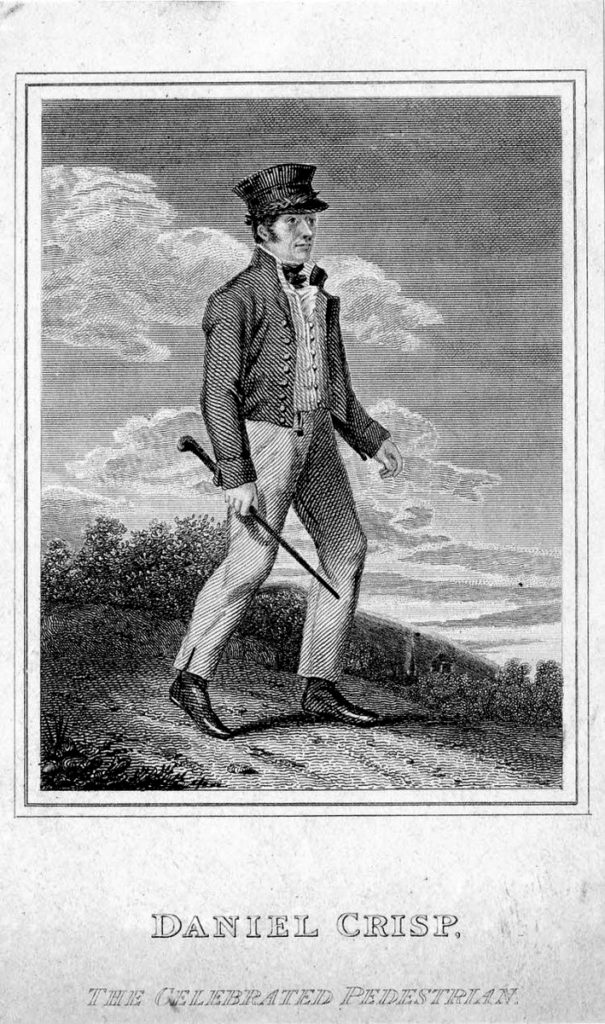

Daniel Crisp – 1818

Crisp did not reach the 404-mile distance in five days, but he did average 75 miles each day for a total of 450 miles in six days. “He was cheered with the most rapturous applause. The bells in Newbury struck a merry peal.” A pair of pigeons were set loose to send news to London. “He was received in town with the cheering of populace, and the ringing of Church bells. He suffered much pain in his feet, and one of his legs and his left hand were a little swelled.” A collection was taken up for Crisp, but it was said to be “very inconsiderable.”

The furthest miles accomplished in six days during those very early years was perhaps accomplished by Rimmington, a farmer, in 1811, who reputedly walked 480 miles/637km in less than six days in Holt, Dorchester, England. He continued on another day and reached 560 miles and won 200 guineas.

The Six-Day Craze of 1822-1825

For some reason, a six-day craze erupted in 1822 as many of the prominent pedestrians made their attempt to reach 400 miles within six days or less. During this era, there were many British pedestrians who had been involved in walking sub-24-hour 100-milers and some had even walked distances of 1,000 miles or further. (See episodes 17 and 18). Early in 1822, one of these famous pedestrians likely attempted the six-day challenge which resurfaced the earlier stories of Foster Powell’s accomplishments in detail. That prompted the public to be interested in making wagers to see if their favorite pedestrian could break Powell’s records. It is estimated that several dozen made the six-day attempt during this craze. A few are highlighted.

During late April 1822, Captain Slowman accomplished a six-day walk of about 354 miles from London to Weatherby and back. He was accompanied by two people in a carriage, would run about six miles an hour, and finished, “much fatigued.”

During October 1822, there were at least three pedestrians on the Great North Road attempting the six-day challenge going from London to York and back. John Phipps Townsend (1791-1845), age 30, famous for his backward walking, took on a massive wager to make the six-day walk in less time than Powell did in 1773.

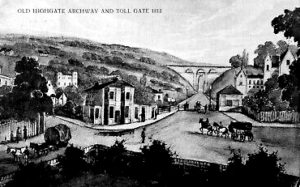

During the early 1800s, toll booths sprang up along the road to collect tolls. Even Pedestrians had to pay a penny to use the stretch through Highgate Arch.

At the same time as Townsend’s attempt, in October 1822, a noted pedestrian John Wright (1770-1844), a 51 year-old tailor from Yorkshire, and army veteran, started off from St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in his attempt to walk from London to York and back in five days. He certainly had the experience. He had previously walked 1,000 miles multiple times in less than 20 days and had walked 420 miles in six days two years earlier at Stroud, England. On the road to York, early on, he became ill and lost about forty-five miles because of it. During that era, Sir Walter Scott called the Great North Road “the dullest road in the world, though the most convenient.” Wright did finish the walk within six days. “It has been an unfortunate failure for the poor fellow, for had he succeeded, he would have been well-rewarded.”

Not all the pedestrians during this era were successful hitting the road for six days. There were likely dozens of failed attempts that never made the newspapers. Hilliard of Chelsea didn’t make it, blaming bad roads. P. Parker of New Cross failed in his attempt to average 70 miles for six days for 100 sovereigns. On his fifth day he only walked 20 miles and had to quit. He did reach 300 miles.

Six-day Challenge Attempts continue in 1823

The six-day “Break Foster Powell’s record” craze continued the next year in 1823. Starting on June 25, 1823, Mark Hawkins of Lancashire, walked the 400 miles from London to York and back in five days in 11.5 hours, beating Powell’s best. He had reached the 200-mile stone on the road in 62 hours and was accompanied by a man on horseback. Plagued by blisters on day four, he pressed on walking 65 miles that day. Upon finishing, it was proclaimed to be “the greatest pedestrian match on record.”

Six-day Challenge Attempts continue in 1824

On August 16, 1824, pedestrian, Alfred MacGowal, age 24, of Durham, England set out on the six-day feat. He walked back and forth on a 200-mile route on the Carlisle Road between Shoreditch Church in London and Boroughbridge for a massive wager of 200 sovereigns. He was required to beat Powell’s 1792 fastest-known-time by at least an hour, finishing before five days, 12 hours. MacGowal needed to average about 73 miles per day and had a goal of reaching the 200-mile half-way mark within 54 hours.

The press commented, “This is most decidedly the greatest undertaking ever tried by any pedestrian, and it excites much sporting interest.” Day one went well. He reached 75 miles, never stopping for more than an hour at once. He indeed reached 200 miles in only 54 hours and was reported as being well and confident in winning. On day five at 2 a.m., he struggled badly for the first time but still pushed to reach 54 miles that day, leaving him only 31 miles for that last 12 hours on day six. He succeeded in returning to London, reaching 400 miles in five days, 11 hours, and 40 minutes.

And then there was the bizarre attempt that took place in November 1824. Richard Sutton, “the Kentish Pedestrian” made his six-day attempt back and forth on the lower Bristol Road in Bath without making one turn. What, how can that be? Sutton would walk one mile forward and then backwards one mile. During his crazy effort, he was annoyed by the poor state of the road and by the travelers crowding the road. Amazingly, he accomplished his goal of reaching 300 miles in six days. It was reported, “The powers of this pedestrian on the backward steps are truly astonishing.”

Six-day Challenge Attempts Concludes in 1825

The six-day craze spread to Scotland too. In 1825, Mr. Barclay, “the Scottish Pedestrian,” and no relation to the famous pedestrian Captain Barclay, claimed to have completed 406 miles in 140 hours, going from Walshford to Glasgow and back. He walked 72 miles the first day. His wager winnings scarcely covered his expenses. Also in 1825, Abernethy, “the North Country Pedestrian” was successful. He walked 412 miles from London to Glasgow in six days and six hours for only traveling expenses. He also accomplished the traditional London-York six-day the next year in five days, eight hours.

Others who accomplished the six-day challenge during these frenzy years included, Robert Skipper, Bullock, Captain Farmer, and Irvine

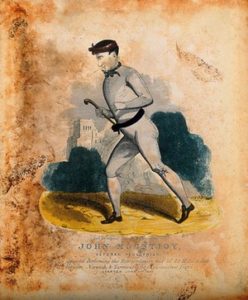

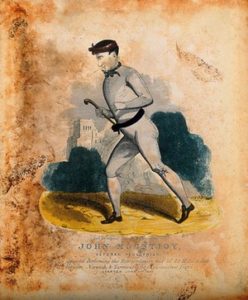

John Mountjoy – Six-Day Specialist

In 1840, Mountjoy accomplished his most impressive six-day challenge. His wager required him to run for six days from Norwich to Yarmouth and back, twice each day, 79 miles each day, for a total of 468 miles in six days. Mountjoy was very poor and started out alone, doing the run unsupported. “So poor indeed was he, that he had no change of clothes, and when wet to the skin on the fourth day was indebted to the kindness of some gentlemen who brought him articles needed.”

As the years passed, there were a few other successful six-day accomplishments. By 1873, no one had yet reached 500 miles in six days.

Stay tuned for the next part when P.T. Barnum of circus fame, (“There’s a sucker born every minute”) was instrumental in organizing the first known six-day race in America and the 500-mile barrier is finally broken.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Andy Milroy, The History of the 6 Day Race

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- P. S. Marshall, Richard Manks and the Pedestrians

- Andrew Green, “Foster Powell, the great pedestrian”

- Charles G. Harper, The Great North Road: London to York

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Norwood, Richard

- Leeds Intelligencer (England), Feb 17, 1767

- Kentish Gazette (England), Oct 2, 1787

- Maryland Gazette (Annapolis, Maryland), Jul 8, 1790

- Manchester Mercury (England), Apr 23, 1793

- Jackson’s Oxford Journal (Oxfordshire, England), Feb 27, 1808

- Salisbury and Winchester Journal (England), Apr 4, 1808

- The Derby Mercury (Derbyshire, England), Dec 24, 1773, Mar 18, 1774, Jun 5, 1788, Jul 2, 1823

- The Public Advertiser (London, England), Nov 3, 1790

- The Leeds Intelligencer and Yorkshire General Advertiser (West Yorkshire, England), Apr 22, 1793, Nov 12, 1821, Nov 2, 1822

- The Ipswich Journal (Suffolk, England), Apr 27, 1793, Apr 16, 1808, Aug 28, 1824

- The Hull Packet and East Riding Times (Hull, England), Jul 7, 1818

- The Hull Packet (Hull, England), Sep 29, 1818

- Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle (Portsmouth, England), Sep 28, 1818

- The Morning Post (London, England), Apr 27, May 7, Oct 21, 1822, Dec 16, 1823, Aug 19,23, 1824, Mar 10, Aug 22, 1825, Sep 24, 1839

- Morning Herald (London, England), Oct 26, 1822

- Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (England), Oct 20, 1822

- Sheffield Independent (England), Mov 2, 1822

- London Packet and New Lloyd’s Evening Post (England), Jun 23, 1823

- The Times (London, England), Aug 21, 1824

- The Morning Chronicle (London, England), Apr 27, Nov 25, 1822, Aug 24, 1824

- The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post (Bristol, England), Mar 16, 1822

- Berrow’s Worcester Journal (England), May 9, 1822, Dec 23, 1824

- The Leeds Mercury (Leeds, England), May 10, 1823

- The Observer (London, England), Mar 7,21, 1825

- The Star (London, England), Oct 13, 1826

- Norwich Mercury (England), Jul 4, 1840

- The Exeter Flying Post (Exeter, England), May 1, 1851

- Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, Sep 28, 1878

- Luton Times and Advertiser (England), Mar 7, 1879

- Sporting Life, May 26, 188