Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:08 — 35.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

The six-day challenge (running as far as you could in six days) originally started in England during the late 1700s. Fifty years later, in the 1820s, a six-day frenzy occurred as many British athletes sought to reach 400 or more miles in six days (see episode 91). But then, six-day attempts were essentially lost for the next 50 years. Surprisingly, it was the Americans who resurrected these events in the early 1870s and brought them indoors for all to witness.

The six-day challenge (running as far as you could in six days) originally started in England during the late 1700s. Fifty years later, in the 1820s, a six-day frenzy occurred as many British athletes sought to reach 400 or more miles in six days (see episode 91). But then, six-day attempts were essentially lost for the next 50 years. Surprisingly, it was the Americans who resurrected these events in the early 1870s and brought them indoors for all to witness.

The Brits believed they owned the running sport and surely their athletes were superior and could beat the upstart Americans, Edward Payson Weston and Daniel O’Leary. It was written, “They cannot be expected to be much better than those bred in England.” Both American and British runners/walkers wanted to prove that they were the best and challenges were sent back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean. The British did not realize that in 1875, there was no one truly skilled and trained in England to do heel-toe walking for the distances that Weston and O’Leary were doing in America. Thus, Weston took the English bait and boarded a steamship to England.

| Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

British Pedestrian Talent

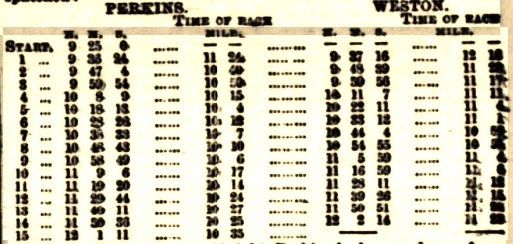

The current Pedestrian hero in England was William T. Perkins, “The Champion Walker in England.” On September 20, 1875, at the Lillie Bridge grounds in London, England, the home of the London Athletic Club, he covered eight miles in 59:05 in front of 5,000 people. In England “Pedestrianism” was not limited to walking, it included distance running and short-distance “sprint running.” But interest was low. During December 1875, a Sporting newspaper wrote, “Professional pedestrianism is at its lowest ebb in London.” The first long-distance running race, professional or amateur in more than a year was scheduled for December 26th that year, a ten mile-race held at Lillie Bridge.

Reaction in England to Weston-O’Leary Race

British sports writers doubted the results of the December 1875 Weston-O’Leary six-day race in Chicago won by O’Leary (see episode 98). A respected British sportswriter, Easterling, wrote, “Either O’Leary is a wonder of endurance such as has never been before even dream of, or he isn’t, and that can only be tested by his walking against some known man round a large ground or on a road. Not to mince matters, the reason we Englishmen only believe what we see of American prowess, is the extreme untruthfulness of American sportsmen.”

A running/walking expert in London carefully looked over the statistics of the Weston-O’Leary six-day race. He was impressed with the amount of data collected but wondered about competing that distance in “a covered building.” Indoor running competitions were not yet taking place in England, and it was believed that there were many British professional athletes who could beat “the Yankee horses,” Weston or O’Leary, easily on roads outside, rather than in comfy looping indoor accommodations, events which they referred to as “dreary tramps.”

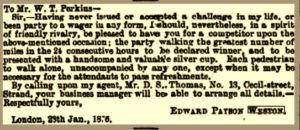

The Brits challenged O’Leary to come to England and walk a mid-distance race against their champion walker, Perkins. During December 1875, a reply was sent from William Curtis (1837-1900), the referee of the Weston-O’Leary race, who boasted in the New York Sportsman: “It would be good betting to wager that any man who is champion of England cannot, on a named day, equal O’Leary’s performance. He will not walk a match at less than 100 miles but will walk any man in the world a match at 100-200 miles for any reasonable amount, say, between $2-5,000.”

At the end of December 1875, Perkins issued a proposal to O’Leary for home-and-home 100-mile matches in American and England. O’Leary agreed and sent a first deposit of 100 pounds to Perkins to start planning for a match first to be held in America. A British sporting newspaper wrote, “O’Leary will have to do something very smart in walking if he is to have any chance of defeating our little wonder.” They thought the Yankee was “cute” but did not stand a chance against Perkins.

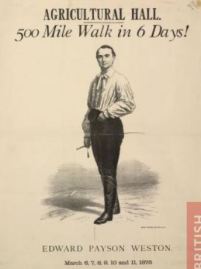

Weston Goes to England

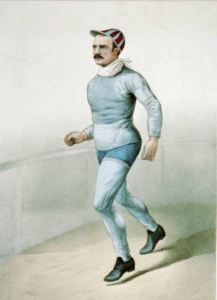

The British press was very skeptical about all of Weston’s claims, especially his 500-miles in six days, which was said to be “rubbish.” They were anxious to see him fail in full view of the British sportsmen. “Edward Payson Weston has arrived in England to convince the skeptical and satisfy the curious. No aspirant for pedestrian honours ever came before the public with such flourish of trumpets.”

Weston was in England for more than a month before he was able to finally put together a walking exhibition. A dozen American residents in London asked him to perform and likely offered funding. They wrote, “believing that an illustration of your marvelous powers of speed and endurance would be of interest to the public, and particularly to the medical profession, respectfully request that you take an early opportunity to give an exhibition of pedestrianism in this city.”

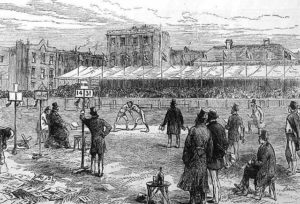

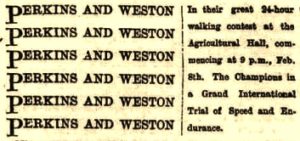

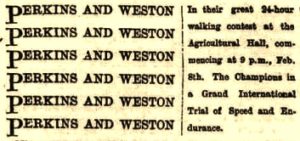

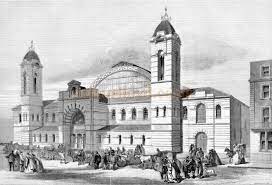

The historic race would be held at the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington, London, the first of many ultrarunning races to be held inside that structure. No Englishman yet dared to race six days against Weston, but this 24-hour race would kick off the golden age of Pedestrianism in England and would open the door to six-day races outside of America.

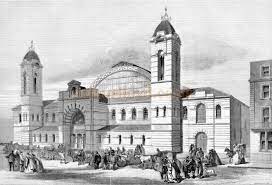

The Agricultural Hall at Islington, London, England

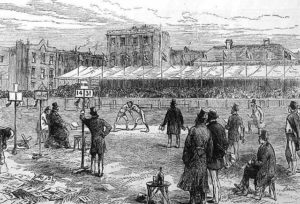

The Agricultural Hall, in Islington, London, England, opened in 1862, built for livestock shows, but was also used for public events and large-scale exhibitions. It sometimes attracted as many 130,000 visitors during a week. It was a massive building, 384 feet by 217 feet. The impressive arched roof was an iron-and glass structure over the massive main hall. At night the interior was lit by 4,000 gaslights with the addition of several giant illuminated chandeliers that hung from the ceiling. It became London’s premier public venue for many types of shows. By 1876 it was used by trapeze artists, bicycle races, horse races, religious services, country fairs, and cattle shows. It could be configured to accommodate 18,000 spectators.

William Perkins

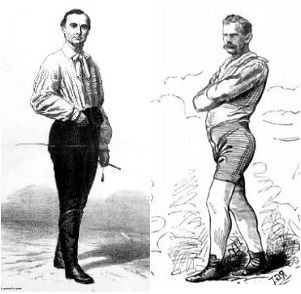

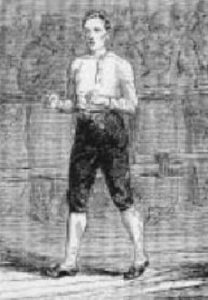

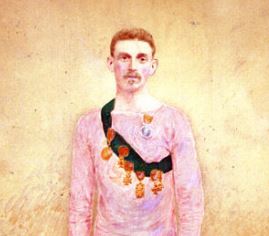

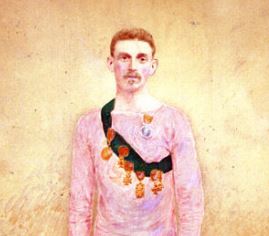

William T. Perkins, age 23, was born in London, England. He was described as “unquestionably the fastest walker we have ever had in England.” He was 5 feet 6, weighed 132 pounds, a “smart-looking young man” with broad shoulders, short back and had very muscular thighs. Even though he was “the champion,” his walking career had covered only a few years.

He had worked his way to fame very quietly since 1869 at the age of only 17 and appeared in several short distance walking races. He achieved his first win in 1870, at the age of eighteen. In 1874, he won a three-mile championship against Joe Stockwell, of Camberwell, England, “one of the finest and fastest walkers ever seen” and beat him easily, giving him his champion title. Perkin’s eight-mile walk in under an hour in September 1875 at the Lillie Bridge grounds was considered by the British as being the “summit of pedestrian accomplishments.” After Weston arrived in England, Perkins had anticipated a match against him and had been training for several week weeks at Nottingham with his trainer, John Boot (1838-1920). To make sure Perkins could go long distances, he gave an exhibition with an 18-mile test walk that went well in 2:34.

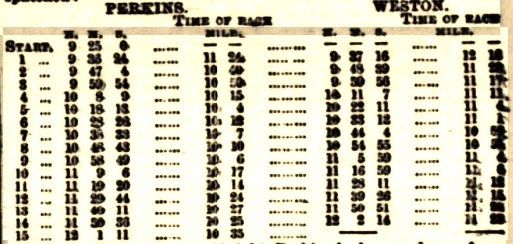

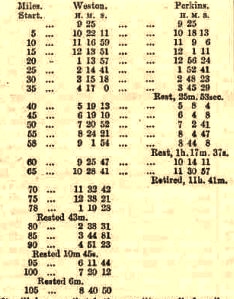

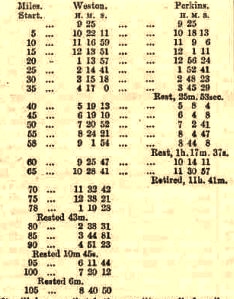

Weston vs. Perkins

The British were thrilled to see Perkins building a nice lead. “It at once became apparent that Perkins is far better than his opponent. Perkins’s style is simply perfect, with long rapid strikes, striking well out from the hips. He covers the ground at a tremendous pace and uses his arms in a way that seems to help him along. Weston on the other hand, reminds one of a country farmer swinging along when trying to make up for lost time.”

After all had been cleared out except for the walkers, handlers, judges, and press, “the only audible sounds were the tread of the pedestrians and the voices of the judges marking the laps and time. As the small hours drew on the pedestrians pursued their monotonous pilgrimage through the gloom like phantoms of the night.”

Weston took the lead at mile 59. Perkins’ boots were full of blood and his bloody socks had to be cut off his feet. He finally quit after reaching 65 miles and Weston went on to reach 100 miles in 21:55 with loud cheers and finished with 109 miles in the allotted 24 hours. He walked an extra lap as officials cleared the way for him with umbrellas and sticks, and then he was “fairly mobbed” by the adoring crowd. “The crowd outside increased and they broke open the doors and filled the hall, cheering the victor loudly.”

British Reaction to the Defeat

Also from London: “All staunch patriots are somewhat crest-fallen today. Our champion walker has been beaten by the champion walker of America. Every true Briton had laughed to scorn the bragging of Weston, who had blown his own trumpet so loudly that its echo had reached across the Atlantic.”

Perkins was also humbled and admitted that he had been beat easily by Weston in “a performance which has never been equaled in this country.” He knew that no pedestrian in England had an “earthly chance keeping up with” Weston until they did proper strict training for ultra-distances. O’Leary, hearing of the victory, was anxious to leave for England to prove that he could also beat Perkins. However, Perkins wisely cancelled the match with O’Leary that was scheduled for March.

America’s Reaction to Their Victory

![]()

![]()

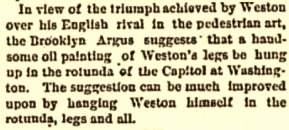

Yes, many newspapers couldn’t help themselves and take shots at Weston. In Detroit, the headline was, “Weston, the Pedestrian, Finds a Worse Failure than Himself.” In Chicago, O’Leary’s hometown: “Weston the walker, who has been beaten by nearly every pedestrian of note in America, has a last achieved a victory. Knowing from experience that competition with his own countrymen was a useless expenditure of wind and muscle on his part, he went to London and defeated Perkins. He had better remain in London.” In Cincinnati, Ohio, “Aha! Our American pedestrian, Weston, has beaten the English champion. Now is the time to die covered with glory, and the 50 pounds he has won will cover his funeral expenses.”

Weston Continued to Win in England

Weston issued more challenges and the British news commented, “That Weston will achieve the best performances on record from upwards of a hundred miles, we have but little doubt.” Weston next soundly beat Alexander Clark in a 48-hour race. Clark had previously held the fastest known time in England, walking 50 miles but could only manage 54 miles against Weston, who reached 180 miles. Weston even played “God Save the Queen” at times on his cornet as he walked. During this race, a spectator fell from the girders under the roof breaking his arm in three places and losing some teeth. He was rushed to the hospital “frightfully mutilated and insensible.”

How would Weston perform, competing against a true runner? Next up was a 75-hour match against Charles Rowell (1852-1909), a Cambridge rower, and a fairly new pedestrian who would eventually become one of the greatest ultrarunners ever. He was allowed to run as Weston walked, and went out to an early big lead. But on this occasion, even with running, he was no match for Weston who crushed him with 275 miles to 176.

The First Six-Day Race in England

The Six-Day Competitors

Weston offered a cup valued at 100 pounds to anyone who could walk further than him in six days. Many men sent letters into The Sporting Life newspaper, applying to compete, but when race day came, only two daring runners showed up at the start.

Alfred Taylor, age 32, was a former soldier who had experience going on a march walking 50 miles a day for six days in the hot sun while stationed in India. He was a typesetter who showed up just in time to participate.

James Martin, age 52 of Maidstone, England, was also a former soldier and war hero who served in India and Crimea where he was severely wounded. He was a veteran ultrarunner, the current 50-mile world record holder, which he set back in 1863, running on the Maidstone Turnpike from London to Hereford in 6:17. He would hold that world record until 1879. His participation was somewhat honorary, but he planned to go as far as he could and then trade off with another walker, W. Newman.

Day One

Martin took a bad fall around mile seven. “He fell forward onto his face near the western end in a fainting state, but after cold water was applied to his head and neck, he was able to resume his journey after a stoppage of about three minutes.” He went on to really struggle during the night.

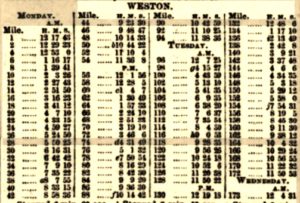

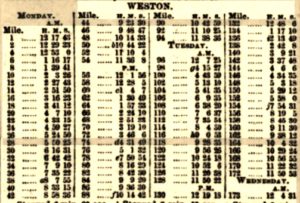

By 10 a.m. Weston was at mile 47, Taylor 45, and Martin 23. After 70 miles, Weston stretched out his lead. He reached 95 miles during the first day.

Day Two

Later in the afternoon of day two, “Martin, in accordance with medical advice, was ordered to leave the track, his place supplied by a man called Newman. Taylor was ordered to bed by the judges in consequence of his prostrate condition and told to rest until the morning.”

W. Newman was from Somerstown England, and had previously won two 20-mile races. It certainly was unwise to have these low-mileage runners trying to complete. Newton started at 8:45 p.m. when Weston was at 158 miles and started out at a tremendously fast pace. At the end of day two, Weston had reached mile 173.

Day Three

By 1 p.m., Weston was at 209 miles, Taylor 120, and Newman 50. Reporters used a mobile telegraph office that was set up on the north side of the hall where they could send reports to newspapers all over the world. At noon, the medical stuff declared that Taylor was unfit to continue. He protested, but he was ordered by the judges to leave the track. His total distance was 122 miles. It was said that Weston’s competitors “had subsided like mist before the rising sun.”

The Finish

When the pistol fired signaling the end of the 144 hours, Weston had reached 450 miles. He climbed into the judges’ box and gave a short speech, thanking everyone for their kindness and expressed his affection for England. The great sportsman, Sir John Dugdale Astley (1828-1894), who would in the future play a prominent role in the promotion of six-day races, was in the box and congratulated Weston. Weston was then carried away in triumph to a room in the hall to get some rest. Newman ended his walk with an impressive 190 miles in a little more than four days.

Coca Leaves Scandal

Finally, the scandal forced Weston to write a letter to a London newspaper. He admitted that he also chewed on the coca leaves during his 24-hour race with Perkins and said they did not enhance his performance, but only helped him to prepare to sleep. He also admitted to using them in previous events in America. He wrote, “Nature should not be outraged by the use of artificial stimulants in any protracted trial.” Surprisingly, the British seemed to accept his explanation. America’s reaction was less forgiving, and coca was touted as being the secret to Weston’s endurance.

Within a month, professors at Edinburgh, Scotland soon tested the use of coca with endurance walking and discovered that it reduced the pulse and fatigue. Over the years the use of coca leaves has proved to act as a mild stimulant that suppresses hunger, thirst, pain, and fatigue. Its alkaloids are a source of cocaine and now the leaves’ use are illegal in the U.S. and banned by the World Anti-Doping Code.

The British Seek to Beat Weston

Reaction in Britain to the highly publicized six-day race, was similar to what had occurred in America. Others, even without proper training wanted to also get attention by attempting to walk six days, trying to do better than Weston. In London, one reporter wrote, “Several of our countrymen have come forward [boasting] of their ability to beat all that Weston has done in England or America. Only Newman showed anything above form that could not have been surpassed by any ordinary rural postman or policemen.” Joseph Spencer was the first, trying to walk 110 miles in 24 hours in the Agricultural Hall. But after 22 hours and only 75 miles, he could barely walk and was carried off the track “in a helpless condition.”

![]()

![]()

To solve this embarrassment, British athletes were further encouraged by prize money raised by the owners of the Agricultural Hall “to see if England cannot produce a better pedestrian than the American representative, Weston” and race for 24 hours. About 100 men sent in applications to participate, 16 were selected, and 14 started. Weston declined to participate on the single-shared track and he likely feared defeat. On May 8, 1876, the British ultrawalkers were finally successful in England’s first “Great Walking Match of 24 Hours” attended by 5,000 spectators. Henry “Harry” Vaughan (1848-1888), age 27, a carpenter/architect from Chester, England, nearly six feet tall, broke O’Leary’s 100-mile world walking record with 18:51:35 by about two minutes, and also broke Weston’s 24-hour world walking mark (117) with 120 miles. (The current 100-mile running world record was 17:52:00, set by Edward Rayner of Great Britain in 1824, at Biddenden, England). Vaughan returned to his home as a national hero. The British were on their way to compete again in ultrarunning and finally had “taken the wind out of the American walker’s sails.”

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- P. S. Marshall, Henry Vaughan

- Nick and Helen Harris, P. S. Marshall, A Man in a Hurry: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Edward Payson Weston, the World’s Greatest Walker

- Sporting Gazette (England), Dec 11, 1875, Jan 22, 1876

- The Sportsman (London, England), Jan 18, 1876

- Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (England), Dec 11, 25, 1875, Feb 19, 1876

- Weekly Independent (London, England), Dec 11, 1875

- Ulster Examiner and Northern Star (Scotland), Dec 8, 1875

- Sporting Times (England), Jan 29, Feb 9, 1876

- Islington Gazette (London, England), Feb 9, 1876

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Feb 10, 1876

- The Morning Herald (Wilmington, Delaware), Feb 10, 1876

- Glasgow Herald (Scotland), Feb 10, 1876

- The Yorkshire Herald (York, England), Feb 8, 10, 14, 1976

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 10, 1876

- The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), Feb 12, 1876

- Sporting Life (London, England), Jan 29, Feb 12, Mar 4-5, 8, 11, 15, 25, April 1, May 13, 1876

- The Pittsburgh Commercial (Pennsylvania), Feb 12, 1876

- Chicago Weekly Post and Mail (Illinois), Feb 17, 1876

- Globe (London, England), Jan 29, Feb 9, 1876

- Sheffield Daily Telegraph (Yorkshire, England), Feb 2, 1876

- The Isle of Man Weekly Times (Douglas, Isle of Man, England), Feb 12, 1876

- Reynold’s Newspaper (London, England), Feb 13, 1876

- Nottinghamshire Guardian (England), Feb 11, 1876

- The Standard (London, England), Mar 6, 1876

- London Evening Standard, March 8, 1876.

- York Herald (Yorkshire, England), Mar 8, 1876

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Mar 8, 1876

- The Leeds Mercury (West Yorkshire, England), Mar 18, 1876