Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:30 — 30.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Signup and get a bonus episode about the first major six-day race held in California. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

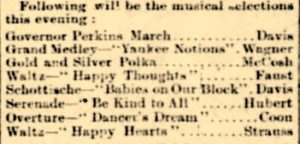

Women’s International Six-Day

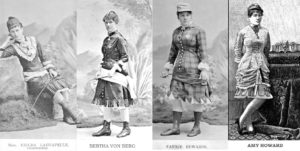

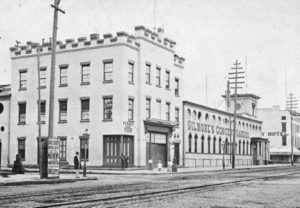

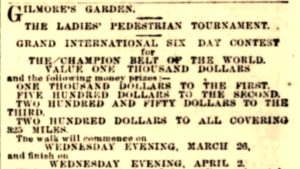

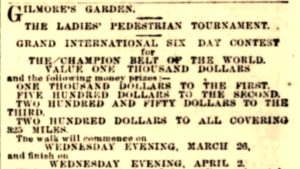

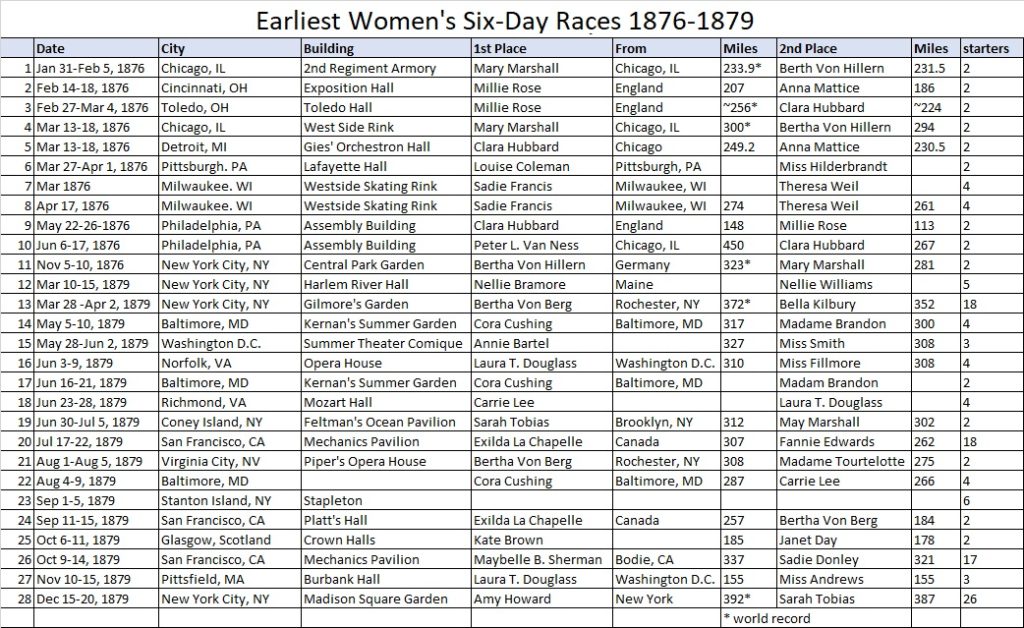

After the Third Astley Belt Race was concluded in New York City’s Gilmore’s Garden (Madison Square Garden) on March 15, 1879, (see episode 109), it was quickly announced that a “Grand Ladies’ International Six-Day Race” would also be held at Gilmore’s Garden in less than two weeks. It would be the first “go-as-you-please” (running-allowed) six-days race for women. Yes, women would start running to the shock of the Victorian Age public.

For the first time, a women’s ultrarunning race would include spectacular prizes for the winner. The first-place prize would be $1,000 ($28,750 value today) in cash along with a belt similar to the Astley belt, called the “Walton Belt” made by Tiffany valued at $250. The manager of the race was Francis Theodore “Plunger” Walton (1837-1911), a racehorse man and manager of the St. James Hotel in New York City. A hefty entrant’s fee of $200 was required to ensure that only the most serious women pedestrians would participate. All women who reached 325 miles, would get their fee back.

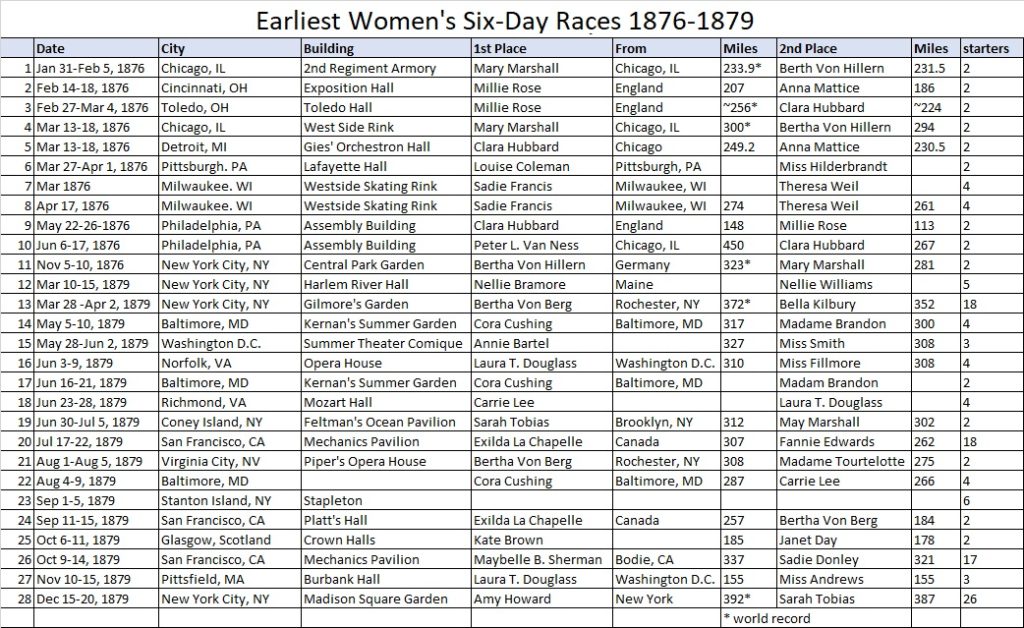

Many women athletes expressed interest, including a number of amateur pedestrians trying to break into the sport. The same track for the Third Astley Belt race would be used. Army tents were provided for each competitor and three medical attendants would take care of them during the race.

The Start

![]()

![]()

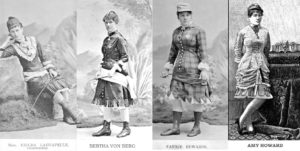

As usual, the press commented about the dress of the female pedestrians. “The dress of most of the walkers is as unsuitable for successful pedestrianism as it can well be made. All the dresses are short and reach but a little below the knee. Instead of being made of flannel and as simply as possible, most of them are heavy garments of velvet, and many are covered with embarrassing bows, and knots of ribbon. The foot gears various, and while some are neatly and sensibly shod with laced boots, others wear low dancing slippers that will quickly fill with sawdust and cause trouble to the wearers.”

The poor women had to endure laughing and insulting remarks from the crowds of men who would hang over the rail surrounding the track. Some of the women runners would blush and look down, but most would just face their tormentors with brazen looks and often answer back boldly.

Exilda La Chapelle

At age 19, in 1878, being called, “Madame La Chapelle,” she walked 336 miles from Montreal to Toronto in 100 hours. Later that year in a competition with a man, Phil Dugan, Jr. (1854-1935) of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on a track, he hit her twice with his elbows as she tried to pass him. She gave him a good slap in the face as she left the track.

She was described as “a small woman, compactly built, straight as an arrow and possesses wonderful endurance. She is very pleasant in appearance. She walks without effort.”

From January 25-February 22, 1879, she walked 2,700 quarter miles, in 2,700 consecutive quarter hours at Folly Theatre in Chicago on a tiny track, 28 laps to a mile. The Washington Post critically compared watching her suffer through that accomplishment like viewing the Spanish Inquisition. Her best 50-mile time was accomplished in 8:40, and her best 100-mile time was 25:24. She recently walked ten miles in 1:43:06, thought to be a world walking record for a woman.

Day One

La Chapelle walked the first mile in 10:30 with a two-lap lead already. After only an hour, and 3.7 miles, Marion Cameron of New York, was taken out of the race by her husband because he believed she was being cheated out of laps. She also was upset that she had to share a tent with another contestant and had to disrobe in the presence of strangers.

After 13 hours, the score was: Exilda La Chapelle 53 miles, Ada Wallace 48 miles, Bella Kilburn 45 miles.

La Chapelle held her lead through the entire first day. Her husband of a couple of years, a doctor also from France, William Napolean Derose (1852-), encouraged her to slow down. She quickly became a crowd favorite because of her occasional sprints. “Her gait was nervous and not over easy, but she showed little signs of weariness.” She was described as “small, vivacious and the liveliest walker.” She weighed about 100 pounds and was dressed in blue and white with red stockings. “Her arms keep vigorous time to the movement of her tough, sinewy limbs.”

As the day went on, most of the running turned into walking. By evening, there were about 2,000 spectators watching, with few women in the crowd. At the end of the day, the score was La Chapelle 88 miles, Wallace 75, and Kilbury 73

Day Two

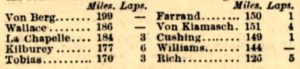

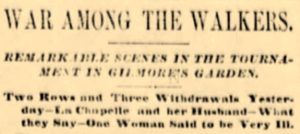

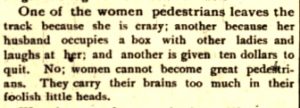

By mid-morning, it was reported, “Many of the starters have already failed and those remaining are so grotesque and miserable in appearance that the boors among the spectators jeer them mercilessly, profanely, and indecently. Altogether it is a disgraceful exhibition for everybody concerned, especially for those who expect to make money out of the women’s suffering.”

“The one redeeming feature of this walk is that no smoking is allowed on the floor of the Garden and the atmosphere is comparatively clear.”

La Chapelle, with 140 miles by evening, continued to walk strongly as if she had just begun, with Bertha Von Berg just ten miles behind. “She and La Chapelle were the first two in the race and a special rivalry seemed to exist between them. Von Berg’s heavy frame was evidently a handicap to her.” La Chapelle was using Charles Rowell’s strategy to follow Von Berg each lap closely to maintain her lead. This started to bug Von Berg. She stopped and said, “If you come within six feet of me again, I’ll slap you in the face.” La Chapelle backed off after that, but she said she would “wipe the floor” with Von Berg’s face. But Von Berg was gaining on her.

Bertha Von Berg

An observer of the six-day race wrote, “Von Berg sails around the track in a delicate mauve-tinted silk. She evinces her purpose in a quiet way to do or die easily. She is one of the finest figures in the procession. She is a large woman, walks with stride and a free swing of arms, and looks as though she were possessed of great powers of endurance.”

Day Three

Ada Wallace was about 30 years old, and from Baltimore, Maryland. She claimed to be the niece of General Joseph Hooker (1814-1879), a general for the Union in the Civil War. He defeated Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville. There is some doubt in the truth of that relation. She was a newcomer to Pedestrianism. In February 1879 she walked 100 miles in 24 hours in New Jersey. In early March she started a walk to attempt 2,058 quarter miles in the same number of quarter hours. After a week she quit because of a lack of spectators, but her judges later admitted her walk was a fraud with long rest sessions, missing nearly five hours per day.

During the six-day race she was described, “Wallace holds a cob in each hand like O’Leary and has high-heeled boots on. She moved with a strong stride in purple tunic and blue stockings. She is solidly built and walks with a steady firm step.”

About 1,500 spectators were in attendance during the evening that showed good enthusiasm toward the women. During the last 15 minutes of the day, Von Berg pushed very hard to reach her 199th mile before the 11 p.m. pistol was fired to mark positions for taking Sunday off. They all were then taken away in carriages to a Turkish bath to rest.

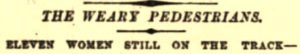

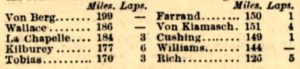

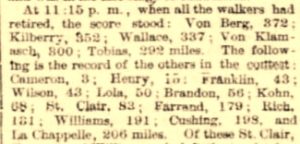

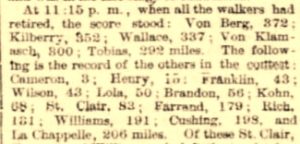

The score after three days was Von Berg 199 miles, Wallace 186, La Chapelle 184.

Day Four

![]()

![]()

Fannie Rich, a book agent from Boston, reversed her direction on the track and would not give the inside lane to the others for some reason. She looked like she was losing her balance and started to collide with the other runners. After being warned by the judges, she retired to her tent, making loud charges of fraud against the scorers. When her trainer tried to reason with her, she hit him over the head with a stick, got a whip and hit respected Referee Edward F. Plummer across the face. She claimed that he pulled out a pistol, but he denied that. She was withdrawn from the race after 131 miles and griped about the unfair conditions she put up with compared to the other ladies.

The strangest highlight of the day took place at about 5:30 a.m. when a drunken man in the audience, flirting with two women in a box began a cruel mocking of La Chapelle as she went around the track. It was soon discovered that he was her husband, William Napoleon Derose (1852-), also of France. She chewed him out in French, and it was such an embarrassment to her, that she decided to quit the race after running 207 miles. She said, “I have made a pail full of money for that man, and he goes and gets drunk. Now he will have to work for his own living.” He pleaded with her to continue, to try to win the second-place money.

The two quickly reconciled but La Chapelle was now irate about the race. She accused someone of trying to drug her and she was clearly mad at Von Berg. “I could gain on Von Berg anytime I wanted, but she wanted to whip me three or four times. She got very mad at me.” She accused the scorers of cheating her on laps, about ten miles. The true breaking point for her was when a scorer put a stick in front of her and wouldn’t let her reverse direction to follow Von Berg closely. Twelve hours later she applied to enter the race again but was rejected by the race management.

Seven runners remained. Eva St. Clair, of Tonbridge England, had not run since the morning of Saturday, day three, and had been lying in her tent for fifty hours. She was finally taken back to her New York apartment “in such a precarious state that serious doubts were entertained as to whether she would live or die.” She was clearly worn out, having two weeks earlier, finished walking 1,250 quarter miles in the same number of quarter hours. The poor lady didn’t have a cent to her name and the next day her landlord tried to evict her, even though she couldn’t even stand up.

The score after day four was: Von Berg 262 miles, Wallace 246, and Kilbury 239. On finishing her last lap of the day, Wallace was nervous about Kilbury gaining on her and bugged by a slow scoreboard updater. She said, “I’ll whip that Dutch scorer for hanging up the wrong figure.” She was also mad at Kilbury for dogging behind her. “She may beat me in her mind, but she can’t in her legs.”

Day Five

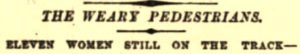

Early on day five, two more women withdrew from the race, leaving only five of the original 18 starters. Von Berg continued to walk strongly with a 23-mile lead over determined sixteen-year-old Bella Kilbury.

Bella Kilbury

By day five, young Kilbury, looking pale and haggard with lines on her forehead indicating suffering, limped along. The doctor had urged her to leave the track, that she would likely ruin her health for life if she continued. She refused and continued in her attempt to keep up with Von Berg. Of the walkers left, Kilbury attracted the most sympathy from the crowd.

Some of the New York press were stunned by what they witnessed. “They struggled on day after day, having no decent places to sleep. Suffering was written in every line of the face, while the steps grew slower and tottering. It was as pitiable a sight as mortals ever were invited to pay 50 cents each to look upon.”

The score after day five was: Von Berg 317 miles, Wallace 296, Kilbury 293.

Day Six

On day six, as the remaining women slept, it was noted that “the spectacle was made still more disgusting by the appearance of stalwart loafers hanging about the tents where the women slept.”

Reaction

Criticism about the women’s race flooded in many newspapers, much of it unfair against women, but some also pointing out the strange drama that took place nearly every day. It painted a picture of crude women parading around, flirting with men in an environment that encouraged the worst dregs of society to act vulgar in full display of the public.

It was clear that many of the women were undertrained who should not have been allowed to complete. They pushed beyond their ability of endurance either by themselves or their backers. A week later a likely false rumor circulated that one of the women had died. Brooklyn proclaimed, “Pedestrianism is a noble and healthful exercise when it is devoted to the right ends, but such a vile exhibition as that which has just closed is totally devoid of any elevating influences. It is high time that something was done to stop these loose women from making themselves conspicuous. Let us go along in the old way, walking when we must, but never utterly abandoning street cars and stages.”

Whether fair or not, much of the public was left with an impression that the race was “public torture of women. One of the most brutal exhibitions afforded the public in some time.” Negative feelings of women pedestrianism were expressed worldwide. England published this statement, “Woman is not physically organized for a six day’s tramp and it is a shame to allow her to abuse herself.”

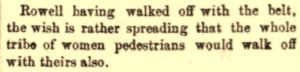

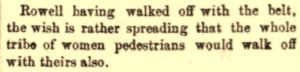

But it wasn’t the end of the women’s six-day race. Just four months later, another such race would be held in San Francisco, California and a massive women’s race would return to New York City by the end of the year.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Harry Hall, The Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars

- Dahn Shulis, “Enduring a life of hardship, Exilda La Chapelle”

- Green Bay Advocate (Wisconsin), Jul 11, 1878

- Champaign Country Herald (Urbana, Illinois), Oct 16, 1878

- The Oshkosh Northwestern (Wisconsin), Dec 13, 1878

- Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Jan 28, 1879

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Mar 24, 1879

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Mar 24, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 22, 25, 27-28, 31, Apr 1-2, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 26-30, Apr 1-2, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 23, 28, 1879

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Mar 25, 1879

- Louis Globe (Missouri), Mar 27, 1879

- The Sun (New York, New York), Mar 28, 31, Apr 1, 1879

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Mar 28, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Mar 28, 1879

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Apr 3, 1879

- Fall River Daily Evening News (Massachusetts), Apr 4, 1879

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Apr 5, 1879

- The Inner Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Apr 8, 1879

- Gloucester Citizen (England), Apr 10, 1879

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Apr 12, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Apr 3, 1879