Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:36 — 32.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

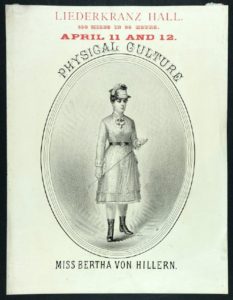

In 1876, Chicago, Illinois was the six-day race capital of the world. A six-day race frenzy broke out in many other cities, after the incredible Mary Marshall vs. Bertha Von Hillern race was held in February 1876. (see episode 101). They showed America that not only could men pile up miles in six days, but women could too, even mothers.

Both men and women sought to race for fame and fortune, even some who weren’t properly trained. There were so many people who wanted a piece of this action that the Chicago Tribune wrote that it would no longer publish challenges unless there was proof that money had been forfeited (secured) for a six-day wager. This new policy was put in place “in view of the extraordinary lunacy which has lately been prevalent among the boys and women of Chicago on the question of walking matches and challenges.”

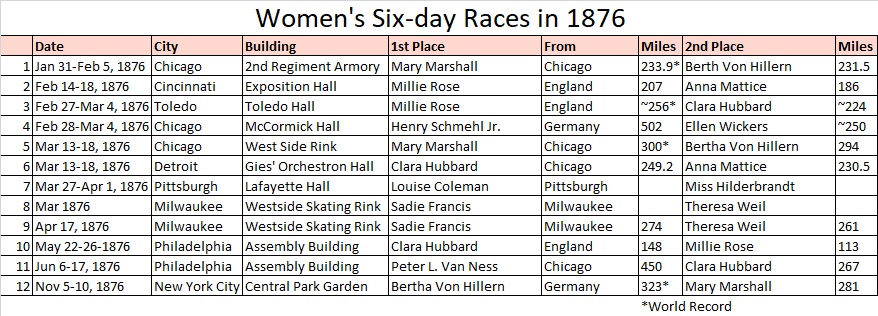

The 1876 six-day craze took place especially among women. This episode will continue to tell the story of the earliest women six-day races. At least twelve six-day races involving women were held in 1876. Pedestrian historians have missed most of this history. The forgotten story has been discovered and can now be told.

| Please consider supporting ultrarunning history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

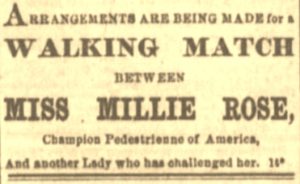

Millie Rose vs. Anna Mattice in Cincinnati

Millie Rose, age 27, the infamous cowhide-wielding fiery pedestrian originally from England, had tasted some of the exciting six-day race between Mary Marshall and Bertha Von Hillern in early February 1876. (See episode 101). She immediately wanted a race of her own and found it in Cincinnati, Ohio. There, she competed against Anna Mattice, a Canadian living in Cincinnati, who was an “older runner.” The race began on February 14, 1876, at the Cincinnati Exposition Hall, on a track measured to be 15 laps to the mile. Rose, who had not yet won a race, claimed to be “the champion female pedestrian of America.”

Millie Rose, age 27, the infamous cowhide-wielding fiery pedestrian originally from England, had tasted some of the exciting six-day race between Mary Marshall and Bertha Von Hillern in early February 1876. (See episode 101). She immediately wanted a race of her own and found it in Cincinnati, Ohio. There, she competed against Anna Mattice, a Canadian living in Cincinnati, who was an “older runner.” The race began on February 14, 1876, at the Cincinnati Exposition Hall, on a track measured to be 15 laps to the mile. Rose, who had not yet won a race, claimed to be “the champion female pedestrian of America.”

For a surprise side-show during this Cincinnati race, Rose’s seven-year-old daughter Louise “Lulu” Rose walked an impressive 10 miles in 2:25:50. In the end, Millie Rose won in a shortened five-day match with 207 miles to Mattice’s 187 miles. Mattice only managed 19 miles on the last day.

For a surprise side-show during this Cincinnati race, Rose’s seven-year-old daughter Louise “Lulu” Rose walked an impressive 10 miles in 2:25:50. In the end, Millie Rose won in a shortened five-day match with 207 miles to Mattice’s 187 miles. Mattice only managed 19 miles on the last day.

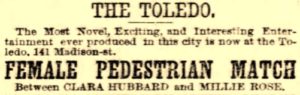

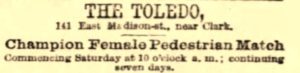

Millie Rose vs. Clara Hubbard in Toledo

With that success, Rose wanted more. Just one week later, on February 26, 1876, another woman’s six-day race was held. At Toledo, Ohio, in Toledo Hall, Rose took on young Clara A. Hubbard (1859-1909), age 18, of Chicago, Illinois. The race started on a Saturday at 10 a.m., probably to attract spectators, instead of the typical early Monday start right after midnight. This race was scheduled for six and a half days.

With that success, Rose wanted more. Just one week later, on February 26, 1876, another woman’s six-day race was held. At Toledo, Ohio, in Toledo Hall, Rose took on young Clara A. Hubbard (1859-1909), age 18, of Chicago, Illinois. The race started on a Saturday at 10 a.m., probably to attract spectators, instead of the typical early Monday start right after midnight. This race was scheduled for six and a half days.

The event attracted great curiosity in Toledo. On day two, more than 1,000 spectators watched as Rose reached 88 miles and Hubbard 77 miles. On day three (after 2.5 days), both were doing well, and the score was Rose 132 and Hubbard 121. Running was obviously permitted or ignored because the women were able to clock amazingly fast miles. Hubbard’s fastest mile was run in 8:22.

The event attracted great curiosity in Toledo. On day two, more than 1,000 spectators watched as Rose reached 88 miles and Hubbard 77 miles. On day three (after 2.5 days), both were doing well, and the score was Rose 132 and Hubbard 121. Running was obviously permitted or ignored because the women were able to clock amazingly fast miles. Hubbard’s fastest mile was run in 8:22.

On day five, Rose’s seven-year-old daughter Lulu, raced against a nine-year-old boy for an hour. She reached five miles in 57 minutes. The little girl, with her mother’s fire, immediately challenged the boy to continue the race to 20 miles, but the boy wisely declined.

Crowd-control was always a problem during these popular events. During the evening, a local bartender forced his way onto the track and refused to leave. “The affair caused a little excitement, but the fellow was ejected in a few minutes and the performance went on. The management took precautions against any such annoying episodes in the future.” Rose was ahead with 204 miles to Hubbard’s 186.

On day six, Rose had a 24-mile lead, but Hubbard was narrowing the deficit fast, and came within 18 miles. But in the evening, Hubbard sprained her ankle severely, tripping on a stone that was on the track. It was speculated, “There seems to be an opinion that the stone did not come there by accident, but that it was deliberately placed on the track by some mischievous person, possibly with a pecuniary interest in securing Miss Hubbard’s defeat.” A doctor diagnosed the sprain to be severe, but she planned to continue the next morning.

After 132 hours, Rose had exceeded the women’s world six-day record of 241 miles. When she reached the six-day 144-hour mark, it is unknown what her world-record split distance was, but it was likely about 256 miles. The two finished on Friday at 11 p.m., after six and a half days (157) hours. The final score was Rose 286 miles, and Hubbard 254 miles.

They both finished in decent shape. “So little were the women affected by their protracted undertaking that at the close of the walk they started off again for a walk, which soon became a run. Millie Rose was presented with the championship medal.” Rose announced that she wanted another race with anyone to try to walk 500 miles for $500 (valued at $13,000 today).

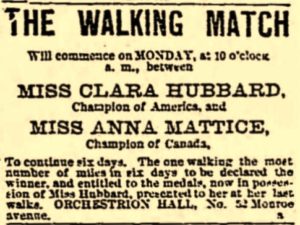

Clara Hubbard vs. Anna Mattice in Detroit

Hubbard quickly signed up for another six-day race, this time in Detroit, Michigan, against Anna Mattice who claimed to be “the champion of Canada.” Both had lost to Rose the previous month. Hubbard, despite not winning any six-day race yet was billed as “The Champion of America.” The race started on March 13, 1876, at 10 a.m. at the George H Gies Orchestrion Hall, a popular cafe/saloon and home of the Detroit Opera House Orchestra and Brass Band.

Hubbard quickly signed up for another six-day race, this time in Detroit, Michigan, against Anna Mattice who claimed to be “the champion of Canada.” Both had lost to Rose the previous month. Hubbard, despite not winning any six-day race yet was billed as “The Champion of America.” The race started on March 13, 1876, at 10 a.m. at the George H Gies Orchestrion Hall, a popular cafe/saloon and home of the Detroit Opera House Orchestra and Brass Band.

The track was six-feet wide, covered with sawdust, and was an extremely tiny 32 laps to a mile. The competitors were described, “Miss Hubbard is a plain-looking person and is apparently very muscular and in good condition. She was attired in a loose-fitting black velvet vest and knee britches trimmed with silver lace, blue and white striped hose and stout high-laced leather shoes. Upon her head was a jaunty little cap, while prominently displayed is the gold championship medal.” Her style of walking was described to be similar to Edward Payson Weston’s, her body and hips swinging while her arms moved with force “rather nervously with the rest of her body.”

Miss Mattice was said to be “an elderly person, quite tall and with no superfluous weight. She was attired in a black dress with a skirt terminating just above the ankles, a loose red jacket, a collar and tie of white lace, red and white striped hose and light leather shoes.” She had a longer stride than Hubbard and carried her arms loosely at her sides, throwing her body and head well forward. After the first half-day, Hubbard was five miles ahead, with twenty-five miles. Mattice suffered an injury to her right foot after getting sawdust into her shoes causing her to fall behind.

At the end, after 5 ½ days (134 hours), Hubbard was the winner with 249.25 miles to 230.5 miles. Sadly, the two only received $25 each for their effort. They complained to the police when their backers failed to pay them the full amount promised and then went off to Cincinnati for another possible “championship stroll.”

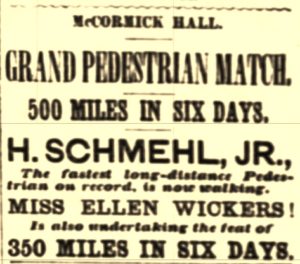

Henry Schmehl vs. Ellen Wickers in Chicago

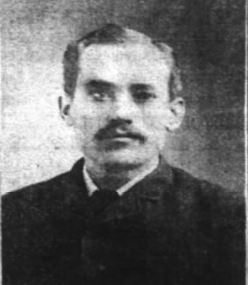

An important pedestrian in the early six-day history who has been overlooked was Henry Schmehl (1851-1932). He was born in Darmstadt Germany, on Sep 6, 1851. At about age 18, in 1870, he emigrated to America and settled in the German-American community in Chicago’s north side. He first worked first in a saloon and then later went into the tailor business, making pants with his father George (1822-1884), and brother George (1859-1897). He entered the pedestrian sport early in 1874, first as an amateur, then became a professional pedestrian, competing for at least 35 years. His first major long-distance walk was in 1874, at age 23, when he accompanied his friend, Daniel O’Leary, also a tailor, on a walk of about 37 miles from Chicago, Illinois to Joliet, Illinois, completed in 8:30. That was a training walk for O’Leary, before he had become famous. By 1876, Schmehl was a strong pedestrian and ready to compete on his own.

Another woman pedestrian came onto the Chicago six-day scene. Ellen Sorkness Wickers (1857-1913) of Chicago was born in Norway. She had competed in several walking matches in Europe before emigrating to America. Early in February 1876, at the age of only 18, she began issuing walking challenges for distances between 50-300 miles against any woman. She also issued a challenge to walk 350 miles against any man going 500 miles. Schmehl took up the challenge.

On February 27, 1876, the same week that Millie Rose was competing against Anna Mattice in Cincinnati, another six-day race started in Chicago, at McCormick Hall, on the north side, between Schmehl, and Wickers. It was the first six-day race in history between a man and a woman. To win the prize, Miss Wickers was given a huge handicap. Schmehl was to reach 500 miles for $500 and Vickers to reach 350 miles for $250. No woman had yet passed 300 miles in six days and the world record for the men was 503 miles held by O’Leary. Because it involved both a man and a woman, it was billed as, “one of the most interesting pedestrian matches ever noted in this city.”

On February 27, 1876, the same week that Millie Rose was competing against Anna Mattice in Cincinnati, another six-day race started in Chicago, at McCormick Hall, on the north side, between Schmehl, and Wickers. It was the first six-day race in history between a man and a woman. To win the prize, Miss Wickers was given a huge handicap. Schmehl was to reach 500 miles for $500 and Vickers to reach 350 miles for $250. No woman had yet passed 300 miles in six days and the world record for the men was 503 miles held by O’Leary. Because it involved both a man and a woman, it was billed as, “one of the most interesting pedestrian matches ever noted in this city.”

The track in McCormick Hall was tiny, 21 laps to a mile. Mayor Harvey Doolittle Colvin (1815-1892) was on hand as the starter. At 9:00 p.m. on Sunday, he shouted, “Go,” and they were off. Schmehl was dressed in black pants, white shirt, red leggings and low-cut shoes. “He is a tall young man, weighing about 145 pounds, and trained into first-class condition. His stride is very long and easy. He certainly does not lack speed. Miss Wickers is a pleasant-faced young woman, with an excellent easy gait which looks as if it might endure. She wore too heavy clothing, and it is pretty clear that heavy dresses, hats, and feathers will have to give way before the first 100 miles are registered.”

Schmehl reached 50 miles in 9:08:54 and 100 miles in 24:44:35 when Wickers was at 55 miles. Earlier in the day, as often happened in these less formal early six-day races, it was discovered that the track had been measured wrong, requiring Schmehl to do 33 extra laps before reaching his 100-mile mark. His 100th mile was clocked at 6:40 which obviously was on the run, not true heel-toe walking. He fueled on a large amount of beef and coffee.

On day three, at determined Schmehl, reached 253 miles, consisting of a dizzy 5,400 laps. Daniel O’Leary visited, paced a few laps, and gave high praise about his friend’s walking style and accomplishment thus far, despite the small track that required so many turns. His doctor commented that because of all the turns, Schmehl’s brain was in a condition that prevented him from sleeping soundly on his breaks.

Miss Wickers reached 144 miles on day three. It was commented, “she shows an endurance that has not as yet been surpassed by any female pedestrian in this city. Her splendid pluck and endurance are rapidly gaining the sympathies of the audiences, who frequently present her with flowers and bouquets.”

On Day four, Schmehl’s uncle came and walked some laps with his nephew. “When the match began, the old gentleman was greatly opposed to the idea, but now he is as anxious about the success of his young relative as it is possible for any man to be.” He reached mile 336, feeling well. Wickers reached 186 miles.

For day five, the hall was packed, mostly with Germans, to watch their new home-country hero. Schemhl reached 404 miles, leaving him 24 hours to cover 96 miles to reach 500, a very difficult task. He felt confident that he could still reach that milestone if he could speed up a bit. Wickers was at 220 miles.

For day five, the hall was packed, mostly with Germans, to watch their new home-country hero. Schemhl reached 404 miles, leaving him 24 hours to cover 96 miles to reach 500, a very difficult task. He felt confident that he could still reach that milestone if he could speed up a bit. Wickers was at 220 miles.

Surprisingly, Schemhl succeeded, reaching 502 miles in 144 hours, just a mile short of O’Leary’s world record. Wickers likely reached 250 miles, but far off her goal. Later, a Chicago newspaper stated that Schmehl was fraud, that the judges and timers had falsified his milage. But Schmehl produced affidavits to the contrary. A future race between Schemhl and O’Leary was inevitable, and would be held in San Francisco, California, two months later (will be covered in episode 102).

A rematch between Schemhl and Wickers was held in 1878, in New Orleans, Louisiana, in a 400 to 250 miles race. Schmehl won by only five minutes and twenty seconds, reaching 400 miles in 119:46:25. Sadly in 1880, Ellen Wickers, the mother of two small children and a widow, was judged to be insane and a pauper, and no longer competed. Sadly, there was a pattern during that era of ruling that some women ultrarunners were insane, while that same ruling wasn’t made of men who experienced wild reactions during and after a race. Wickers died in 1913, at the age of 56.

Women’s Six-day Race Scandals

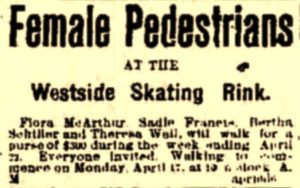

Unfortunately, with this sport, when success was discovered, others emerged who wanted to pursue a path to fame and fortune, and often took short-cuts. On April 17. 1876, at 10 a.m., a six-day race involving four women began in the Westside Skating Rink (West Side Market Hall) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The hall once housed the largest skating rink in the country but had recently been converted to be used as a music hall and farmer’s market.

Mrs. H. B. Boardman of Chicago, a.k.a. “Madame Jane Ferrold,” was the race’s promoter. She was an elderly lady from Chicago, a women’s rights activist who wanted “to show that a woman’s power of endurance is as great as a man’s.” The four walkers were Sadie Francis, Bertha Schiller, Theresa Weil, and Flora McArthur. Apparently these four competed against each other in a similar race a month earlier and Milwaukee was excited for the second race.

Mrs. H. B. Boardman of Chicago, a.k.a. “Madame Jane Ferrold,” was the race’s promoter. She was an elderly lady from Chicago, a women’s rights activist who wanted “to show that a woman’s power of endurance is as great as a man’s.” The four walkers were Sadie Francis, Bertha Schiller, Theresa Weil, and Flora McArthur. Apparently these four competed against each other in a similar race a month earlier and Milwaukee was excited for the second race.

On day three, McArthur, called “the Scottish girl” was suffering from sore feet and eventually dopped out. The scoreboard showed Francis, 137 miles, Schiller, 136 miles, Weil, 135 miles, and McArthur 117 miles. In the end, Francis came away with the win and a promised $300 prize. In 132 hours, she reached 274 miles. Weil came in second with 261 followed by Schiller with 262 and at some point, Jennie Wallace joined in and walked 123 miles. At the end of the race, McArthur came out “in a Scottish suit” and got in a “tussle” with Frances and Schiller. “Miss Francis got away in a round or two and Miss Schiller also found an easy task before her. The novice retired thoroughly vanquished.”

An investigative reporter later revealed that Ferrold’s Milwaukee race had been a farce. “They walked only when they felt like it, and the ‘time man’ who had no watch, manipulated the record at his own sweet will. The receipts were small, and the old lady was hunted down by creditors. After vainly endeavoring to borrow some money from her landlord, she stealthily departed without paying a very large bill.” The reason why McArthur accosted the others at the finish was because she, her sons, and her business manager had been financially drained by the event, leaving them destitute.

Walking in a Haunted Hall

Madame Ferrold moved on to the Exposition Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, for another six-day race. The soon to be demolished buildings were thought to be haunted because of a mass grave on site from a steamboat accident killing 150 people. Many bodies were buried under the floor of the building. The vast wooden structures were described as “dingy, gloomy and grotesque”. The weirdest and strangest noises would occur at intervals all night: Rapping on the ceiling, under the floor, on the doors and windows, and the sound of stealthy footfalls.”

Madame Ferrold moved on to the Exposition Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, for another six-day race. The soon to be demolished buildings were thought to be haunted because of a mass grave on site from a steamboat accident killing 150 people. Many bodies were buried under the floor of the building. The vast wooden structures were described as “dingy, gloomy and grotesque”. The weirdest and strangest noises would occur at intervals all night: Rapping on the ceiling, under the floor, on the doors and windows, and the sound of stealthy footfalls.”

The contestants for this dreary six-day race, who would add footfalls to those of the ghosts were: Julia Reeves, Belle McIntyre and the “Scottish Lassie,” Flora McArthur. However, the race was a bust and only lasted until dusk because Ferrold had no money to deposit for the gas in the building, which was used for the lights. With no lights in the haunted hall, the race was cancelled.

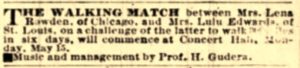

St. Louis Match Problems

Not discouraged, Ferrold next moved on to St. Louis, Missouri, where she organized a six-day race between Lena Rouden of Chicago and Lulu Edwards of St. Louis to be started on May 2, 1876. The women were promised a prize of $500 if either of them reached 300 miles. It was to be held at Uhrig’s Cave and Beer Garden. The building was built above a series of natural, cool caves that were used for brewing and storing beer. A rough track that was too narrow was laid down inside the main building, which also contained a 300-seat theatre.

Not discouraged, Ferrold next moved on to St. Louis, Missouri, where she organized a six-day race between Lena Rouden of Chicago and Lulu Edwards of St. Louis to be started on May 2, 1876. The women were promised a prize of $500 if either of them reached 300 miles. It was to be held at Uhrig’s Cave and Beer Garden. The building was built above a series of natural, cool caves that were used for brewing and storing beer. A rough track that was too narrow was laid down inside the main building, which also contained a 300-seat theatre.

When the inquisitive reporter showed up, there was no race going on. “The proprietor stated that there was a hitch in the financial arrangements. He wanted $25 per day for use of the hall, and all the money in sight was $17.” Ferrold went out trying to raise the $8 needed but wasn’t successful. The rookie walkers had never walked for money before but were experienced book canvassers. They were in over their heads and being taken advantage of by Madame Ferrold.

The reporter concluded his exposé news story with, “The proposed walking match is merely a novel scheme to gull the public and make money, there can be no doubt. Parties capable of wagering $500 would otherwise be able to put up a paltry sum for a hall.” The St. Louis newspaper joked that the race didn’t happen perhaps because new spring bonnets didn’t arrive in time for the women.

Millie Rose vs. Clara Hubbard in Philadelphia

The six-day race came to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for the first time. It was held in the Assembly Building at 10th St. and Chestnut. Millie Rose and Clara Hubbard raced a six-day rematch beginning on May 22, 1876. The track measured 23 laps to a mile and was four feet wide. “Rose was dressed in a white silk body, with blue neck-time, red, white and blue sash around the waist, pink silk trunk, flesh-colored tights, with Oxford ties. Miss Hubbard was dressed in blue-striped silk body, black velvet coat with gold trimmings, black velvet pants, with gold tripes, black and white stockings, and laced gaiters.” The match was stopped short after about three days for some reason. Hubbard won with 148 miles in 33:36:30 (moving time) and Rose reached 113 miles in 25:42:27.

Clara Hubbard vs. Peter Van Ness in Philadelphia

A week later in June 1876, also at Philadelphia, Hubbard competed against a man for six days, Peter L. Van Ness of Philadelphia, who was a new pedestrian. Toward the end she fell on the track twice and was only kept going by stimulants. Finally, she was removed from the hall, taken to the hospital and was in critical condition for several days. She recovered but did not compete again for many months.

A week later in June 1876, also at Philadelphia, Hubbard competed against a man for six days, Peter L. Van Ness of Philadelphia, who was a new pedestrian. Toward the end she fell on the track twice and was only kept going by stimulants. Finally, she was removed from the hall, taken to the hospital and was in critical condition for several days. She recovered but did not compete again for many months.

Marshall vs. Von Hillern in New York City – Third Match

A few months later, inaccurate stories were being circulating in the newspapers about the February match between Mary Marshall (1841-1911) and Bertha Von Hillern (1853-1939) (see episode 101) claiming that Marshall won by 23 miles (she won by 2.5 miles). Von Hillern’s friends stated that she was “much grieved” at the false reports and dared Marshall for another rematch “on equal footing at some place away from Chicago where neither will have a moral or physical advantage.”

Marshall replied that the false facts had not come from her and said, “I shall not agree to another match simply because you dare me.” She wanted a purse of $1000 to be raised, and for the race to be held in Philadelphia since Chicago was objected by Von Hillern. Von Hillern replied that she would agree to a rematch for $1,000 in Boston or New York City.

Marshall replied, “Your formal challenge is received and accepted. As you will not again walk in Chicago, and as you object to Philadelphia, I will name New York City, and any week in November that we can mutually agree upon.”

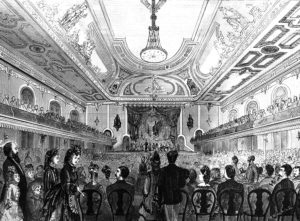

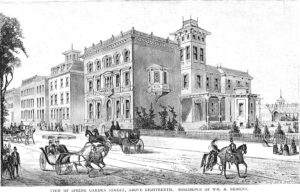

A third race between the two was finally agreed upon to be held at the Central Park Garden, just outside the park, in New York City, on November 5, 1876. Normally the building was used for a restaurant and nightly concerts.

Interest in the rematch in New York City was intense, and they realized this race would be between two very strong women endurance athletes, the greatest women long-distance walkers in the world. “Considerable interest in the match has accrued, as both professional and amateur athletes are anxious to see what a woman can accomplish when brought to the post in good condition. There is some curiosity among medical men to test the powers of endurance of women, and several physicians will be present throughout the contest.”

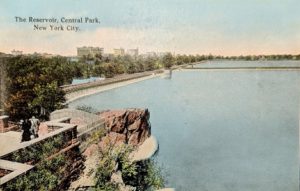

In the weeks leading up to the race, Von Hillern trained hard in New York City and Marshall did the same in Chicago. For many mornings at 6:30 a.m., Von Hillern walked loops around the Central Park Reservoir totaling 20-25 miles without rest. “She then returns to her hotel, and after rubbing and bathing, eats a good hearty noon-day meal of meats, toast, potatoes, oatmeal and stale bread. She takes a little gymnastic exercise in her room and goes to the park at 3 p.m. where she walks another fifteen miles.”

In the weeks leading up to the race, Von Hillern trained hard in New York City and Marshall did the same in Chicago. For many mornings at 6:30 a.m., Von Hillern walked loops around the Central Park Reservoir totaling 20-25 miles without rest. “She then returns to her hotel, and after rubbing and bathing, eats a good hearty noon-day meal of meats, toast, potatoes, oatmeal and stale bread. She takes a little gymnastic exercise in her room and goes to the park at 3 p.m. where she walks another fifteen miles.”

A New York World reporter tracked her down in Central Park and wrote, “Her face is not a handsome one, but is far from being unattractive. The features are somewhat large but well-shaped, and a pair of good hones gray eyes gives life and expression to her face. Her hair is luxuriant, almost golden, and is twisted in a neat coil, firmly fastened on the back of the head. The figure is what almost might be called stocky, so firmly are muscles and bones and flesh knit together.”

Marshall traveled to New York a few days before the race. She was described as “a slight built woman, about five feet three inches in height, and scales some 135 pounds, of a pleasant and ladylike appearance.” Von Hillern was the same height but weighed 110 pounds.

The track inside the hall, measured by the city surveyor, was a tiny 22 laps to a mile, four feet wide, and covered with soil and sawdust, three inches thick. Sleeping rooms were provided for the women on the second floor by a long flight of stairs. They both hoped to reach 400 miles in six days. The world record stood at 300 miles, held by Marshall.

The Start

At the start, very early Monday morning at 12:05 a.m. there were only a small number of spectators. Von Hillern came out in a brown skirt, trimmed with black velvet, and a white jacket. Marshall came out in “a tasteful purple dress, with short skirts, and polonaise trimmed with lace.”

Both wore white kid gloves and little derby hats. Marshall quickly took the lead and looked like she was walking with ease. One observer thought that Von Hillern was trying to imitate the style of male pedestrians, swinging her arms to and fro.

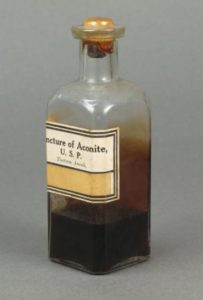

The press tried to explain to New York City how a six-day race between women worked. “During the first 24 hours, it is expected that they will take no sleep and will confine their rests to spells of ten or twelve minutes each. When they come off the track, they will be rubbed by muscular female attendants, and their joints, if they become at all stiff, will be well-rubbed with a liniment composed of chloroform, tincture of camphor and tincture of aconite root. Their bill of fare will consist of two solid meals each day, morning and evening, at which they will be allowed to eat beef and mutton, and while they are walking strong, beef tea and oatmeal with milk.”

The press tried to explain to New York City how a six-day race between women worked. “During the first 24 hours, it is expected that they will take no sleep and will confine their rests to spells of ten or twelve minutes each. When they come off the track, they will be rubbed by muscular female attendants, and their joints, if they become at all stiff, will be well-rubbed with a liniment composed of chloroform, tincture of camphor and tincture of aconite root. Their bill of fare will consist of two solid meals each day, morning and evening, at which they will be allowed to eat beef and mutton, and while they are walking strong, beef tea and oatmeal with milk.”

Day Two – Five

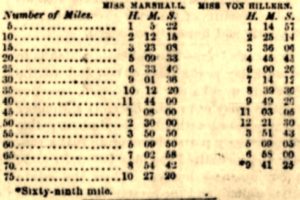

At the end of day one, Marshall had 75 miles and Von Hillern 69 miles. The presidential election returns were announced throughout the evenings, eventually won in a highly disputed election by Rutherford B. Hayes over New York’s Samuel J. Tilden. After day three, Mashall extended her lead to 160 miles to 153. Von Hillern had struggled for long periods but finally recovered her strength.

At the end of day one, Marshall had 75 miles and Von Hillern 69 miles. The presidential election returns were announced throughout the evenings, eventually won in a highly disputed election by Rutherford B. Hayes over New York’s Samuel J. Tilden. After day three, Mashall extended her lead to 160 miles to 153. Von Hillern had struggled for long periods but finally recovered her strength.

“As the race progresses considerable interest is manifested in the effort of these remarkable women and the many physicians who make their daily observations pronounce the task a wonderful one for females.”

On day four, Marshall was walking as if lame, but reached 212 miles. Von Hillern went into the lead, looking much stronger and reached 222 miles. On day five in the evening about 500 spectators watched the women walk. Marshall had a severely sore left foot but still limped around the track twenty-two miles behind. “The struggle between the two lady pedestrians is something like the Presidential contest – a great deal to be said on both sides, but the result still in doubt.”

The Finish

On the last day, Marshall came out looking pale and halting. She had to retire to her tent frequently. In the late morning, Von Hillern completed her 300th mile, going on to break the world record, and Marshall labored to complete her 278th mile. She was having bad chills and was wrapped in fur trimming.

By 3 p.m., Marshall reached her 281st mile and could barely walk. She retired to her tent for a couple hours and came out without any shoes. But still she could not move well, and she stopped again. At 7 p.m., Marshall announced that she was quitting but said she wanted another rematch in the near future. Von Hillern continued, cheered on by Marshall sitting in a chair. Von Hillern finished with 323 miles “amid the crash of the band and the cheers of thousands of spectators.” It was a new women’s six-day world record. The two women were carried triumphantly from the track.

Reaction

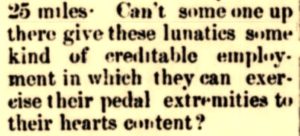

The reaction around the country to the race was mixed. In Louisiana: “Can’t someone up there give these lunatics some kind of creditable employment in which they can exercise their pedal extremities to their hearts’ content?” In Chicago, a letter to the editor called both women “trash” and “a disgrace to all womankind.”

The reaction around the country to the race was mixed. In Louisiana: “Can’t someone up there give these lunatics some kind of creditable employment in which they can exercise their pedal extremities to their hearts’ content?” In Chicago, a letter to the editor called both women “trash” and “a disgrace to all womankind.”

In New Jersey, “What practical benefit will result from all this tramping round of these girls, we do not know. That it will add anything to the physiological knowledge the world possesses, or advance the cause of science generally or specifically, we do not anticipate.” And the usual rude comment, “We should have been more interested in a talking match between two women than in a walking match, though it is probable that in such a contest, neither would stop talking until she dropped dead.”

But others were more reasonable, “Von Hillern’s success is regarded as a surprising demonstration of the possibilities of women’s endurance. It contains a valuable lesson to our girls of the benefits of pedestrian exercise to health.”

Mary Marshall’s Later Years

Mary Marshall blamed her defeat on a lack of training due to the effects of traveling to New York from Chicago. She next turned to challenging men to multi-day walks. Men, including the infamous “Professor” John R. Judd (1836-1911) of Buffalo, New York, came out of the woodwork seeking money, challenging Von Hillern to six-day races.

Mary Marshall blamed her defeat on a lack of training due to the effects of traveling to New York from Chicago. She next turned to challenging men to multi-day walks. Men, including the infamous “Professor” John R. Judd (1836-1911) of Buffalo, New York, came out of the woodwork seeking money, challenging Von Hillern to six-day races.

Marshall tried again to race for six days eight months later in July 1877, at New Bedford, Massachusetts where she suffered terribly. “At times she would hold both hands above her head as if in extreme agony, and many ladies in the audience shed tears of pity. The race committee begged her to stop, but when it was announced that she meant to continue, the large audience applauded enthusiastically, spurring on the fainting woman, who could hardly stand alone, and was almost carried around the track by men who held her up and hurried her on while they fanned her. The band played ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me.’”

During that year, Marshall got involved in a “love triangle” with pedestrian George F. Avery (1854-1885) who called himself, “P.T. Barnam’s Great Pedestrian.” (See episode 94). He had been Marshall’s coach and they became involved. But Avery left Marshall for pedestrian Bertha “Bertie” LeFranc, originally from Paris France, who was only 18 years old. A public scandal resulted in the breakup of Marshall’s marriage. Her husband and son moved to Massachusetts.

Marshall changed her public name to “May Marshall,” but then stopped competing for a time because she was with child and gave birth to Stonewall Lipsey, who was the son of Avery. She returned to competition in 1878, giving the excuse that she had been away because of yellow fever. In 1882 she married pedestrian, Harry Hager. She continued to perform for several years in various publicity stunts, including races against skaters and people pushing wheelbarrows, and died in 1911.

Millie Rose’s Later Years

As for Millie Rose, she continued to compete, often accompanied by her daughter Lulu. She participated in a walking exhibition in Buffalo, New York in Jun 1878 where she experienced a severe attack of neuralgia. She recovered, but then in Pittsburgh she suffered terribly and took all sorts of stimulating fluids including beer and brandy. “When nearing the finish, she utterly collapsed on the track in a pitiable condition.” At her next match, she was struck with an epileptic seizer while on the track.

As for Millie Rose, she continued to compete, often accompanied by her daughter Lulu. She participated in a walking exhibition in Buffalo, New York in Jun 1878 where she experienced a severe attack of neuralgia. She recovered, but then in Pittsburgh she suffered terribly and took all sorts of stimulating fluids including beer and brandy. “When nearing the finish, she utterly collapsed on the track in a pitiable condition.” At her next match, she was struck with an epileptic seizer while on the track.

![]() For the next several months, she was bedridden. She had been remarried about a year earlier, and her new husband had her declared insane, left her, and probably took all of her money. The Boston Globe editorialized about her insanity, “This should serve as a warning to young women who have a mania for pedestrian honors.”

For the next several months, she was bedridden. She had been remarried about a year earlier, and her new husband had her declared insane, left her, and probably took all of her money. The Boston Globe editorialized about her insanity, “This should serve as a warning to young women who have a mania for pedestrian honors.”

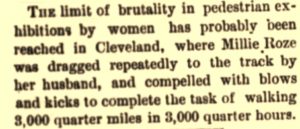

Rose recovered, was back walking in January 1879. In March she competed in Cleveland Ohio in a wager to walk 3,000 quarter miles in 3,000 quarter hours, a quarter mile every 15 minutes for 30 days. But after 28 days, she became faint and exhausted. Her husband was back in her life, and he desperately wanted her to continue on to get the prize money. “He dragged her repeatedly to the track and compelled her with blows and kicks.”

Rose recovered, was back walking in January 1879. In March she competed in Cleveland Ohio in a wager to walk 3,000 quarter miles in 3,000 quarter hours, a quarter mile every 15 minutes for 30 days. But after 28 days, she became faint and exhausted. Her husband was back in her life, and he desperately wanted her to continue on to get the prize money. “He dragged her repeatedly to the track and compelled her with blows and kicks.”

Right after her Cleveland match, she had her husband arrested. “She says that he deceived her with a mock marriage at Rushville, Indiana and that he has since treated her with great inhumanity. She also alleges that he endeavored to practice lewd designs upon her young daughter, pretty Miss Lulu, and that he introduced her to the companionship of a prostitute.”

The newspaper called him “a hard-looking loafer” and reported that he agreed to leave the city and never hurt Millie or Lulu Rose again. A week later, he tried to commit suicide by jumping off a high bridge into a river in Cincinnati with a letter in his pocket blaming Millie for his troubles. A man rescued and resuscitated him but said he acted like a crazy man.

Millie Rose continued to compete with her daughter. Her last known walk was in 1884.

Bertha Von Hillern’s Later Years

Bertha Von Hillern was the undisputed woman champion pedestrian of the world. In late December 1876, she did a solo walk for six days in Boston’s Music Hall and increased her world record to 350 miles. She continued to compete for sixteen more months, with her last walking match coming in April 1878. She then retired from walking competitions. She used much of her winnings to support her aged mother back in Germany, wisely saved the rest, and then went to Boston to study art. She then spent eight months sketching Shenandoah Valley and worked the rest of her life as a talented artist. Bertha Hillern died in 1939 at the age of 86.

Impact of Women Pedestrians

Pedestrian historian, Harry Hall wrote, “Bertha Von Hillern had gone from being an unknown German young woman who barely spoke English into one of the most famous and riches women in America. She had inspired hundreds, if not thousands of women to begin a fitness walking program. Her rivalry with Mary Marshall had started professional women’s pedestrianism in America.”

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Chip Curtis, great-great grandson of Mary Marshall, Family History notes

- How did Cincinatti’s Music Hall get so haunted?

- Uhrig’s Cave

- Harry Hall, Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Feb 15, 1876

- Cincinnati Daily Star (Ohio), Feb 19, 1876

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 29, Mar 2-4, 1876

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Feb 13, 23, 28-29, Mar 2-4, Jun 14, 1876

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 2, 1876

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Mar 10, 14-15, 17-21, 1876

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Mar 30, 1876

- The Daily Milwaukee News (Wisconsin), Apr 20, 23 1876

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Apr 26, 1876

- Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), Apr 25, 1876

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), May 4, 1876

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (West Virgina), May 4, 1876

- The Daily Gazette (Wilmington, Delaware), May 24, 1876

- The Pittsburgh Commercial (Pennsylvania), Mar 24, 1876

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jun 5, 1876

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Jun 17, 1876

- Joseph Saturday Herald (Michigan), May 27, 1876

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Oct 24, Nov 2, 6-11, 13. 1876

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Nov 3, 1876

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Nov 14, 1876

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Nov 15, 1876

- The Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), Nov 7, 1876

- The Sacramento Bee (California), May 6, 1876

- The Monmouth Inquirer (New Jersey), Nov 23, 1876

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Jun 10, 1878

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Nov 8, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Nov 17, 1878

- The Ohio Democrat (New Philadelphia, Ohio), Apr 3, 1879

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Mar 25, Apr 9, 1879

- The Muncie Morning News (Indiana), Apr 16, 1879