Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:12 — 27.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

The sport of ultrarunning during the 19th century was truly filled with tales of strange things that are unthinkable and shocking to us today. This series of episodes presents a collection of the most bizarre, shocking, funny, and head-scratching events that took place in ultrarunning during a 25-year period that began about 150 years ago.

The sport of ultrarunning during the 19th century was truly filled with tales of strange things that are unthinkable and shocking to us today. This series of episodes presents a collection of the most bizarre, shocking, funny, and head-scratching events that took place in ultrarunning during a 25-year period that began about 150 years ago.

The first part covered two strange tales, one shocking and one sad. This episode will report on the “cranky or daffy runners” whose minds turned to mush after several days of running without much sleep. They started to experience hallucinations, doing crazy things, delighting the thousands of spectators who came hoping to watch a train wreck of runners.

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Signup and get a bonus episode about the first major six-day race held in California. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Cranky Runners

For the “pedestrian era” of ultrarunning, more than 120 years ago, spectators hoped to watch a runner go what they called, “cranky” in this reality show. It was said that by hour 36 of a six-day race that runners could be expected to do stranger things as exhaustion and sleep deprivation caused hallucinations. It was explained, “The cranky spell is reached, and the contestants furnish no end of amusement. Their tired brains are in a whirl, and it is only to be expected that the men should act like inmates of a ‘funny house.’”

Missing Runners

Runners would at times go bonkers so badly that they went missing. “One of the leaders suddenly stopped and climbed over the rail and ran into the tent of one of the other contestants. He was missed by his trainers who eventually found him and dragged him out, and in a few minutes was back on the track going around as steadily as ever.”

James Dean, of Boston, Massachusetts, one of the brave black runners of the era was a stenographer. During a race, he suddenly accused his crew of attempting to poison him and then would not accept food from them unless it was first tasted by someone to prove that it wasn’t poisoned. After he reached 412 miles on the last day of his six-day race, he was in a “daffy” condition, and he was taken to the hospital. He then escaped his attendants while in the bathroom. He went through an open window and down a fire escape.

“A search was at once instituted and kept up for several hours without finding any trace of the missing racer.” He was later found wandering the streets and was taken to the police station. “His clothing was covered with blood, the result of a hemorrhage from his nose. He was ragged and covered with dirt. He was wholly irrational and babbled meaninglessly.” His trainer, the former champion of the world, Frank Hart (1857-1908), soon arrived and took the “demented man” to St. Francis Hospital. “It is said that Dean was completely broken down from his exertions in the race. He will probably recover after rest and treatment.” After another day in the hospital, Dean recovered well and two months later was again competing in a six-day race.

Hallucinations

Charles Harriman (1853-1919), a shoemaker from Massachusetts also experienced this hallucination. He said, “No part of the track seemed level. I was constantly walking uphill or downhill. In Madison Square Garden, on the north side, there seemed to be a hill so steep that I could hardly climb it. When I turned south, it was just as easy as could be and just like slipping down a toboggan shoot.”

Doctors were intrigued by these hallucinations. “The walker imagines that he is walking up and down a hill. No part of the level track is level to him, it is a series of hills and valleys. The phenomenon results from looking intently at the track for a long time. It produces a peculiar effect upon the optic nerve.”

Sammy Day (1847-1913), an Englishman from McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, believed that on day two of a race, that he had won the six-day race and was only continuing to amuse his Pittsburgh friends, singing most of the time. Tom Beachmont, (1875-1950) of New Hampshire, also imagined he had won the race, and wanted the race management to pay him the first-place prize. His trainer had a lot of trouble keeping him on the track, but toward evening, he was all right again.

George Cartwright (1848-1928), of England, stopped during a six-day race and commented to his trainer, Henry Seeley, “’Say, Hank, I just got through the woods back there all right, but I don’t know about climbing that mountain there,’ and he pointed down the track.” Seeley asked if he dodged the trees all right. Cartwright said they were pretty thick. He was encouraged to just follow the runner ahead of him.

Another runner, William Nolan of Denver, Colorado, imagined that someone had changed his shoes while he had slept and had given him a pair with soles so long that he was in danger of tripping himself. He said, “They go all right up the stretches, but I am afraid at the turns.” Sleep didn’t seem to help get this notion out of his head. When he finally quit the race for good, he still believed that he had strange shoes.

Harriman experienced a similar hallucination. He imagined that he was passing over a railroad bridge where the ties were very far apart. “For over an hour, he strode about the track, covering three feet or more at every step, occasionally stopping with his feet close together to collect himself.” His trainer could not convince him that the track was solid. Harriman said, “I walked miles behind another man putting my feet where his had been and all of the while firmly convinced that I was walking on railroad ties. Every now and then a hallucination would come to me that I was on a high bridge and that I must be careful and not fall through.”

Another troublesome thing was hearing strange sounds, mostly in the early morning hours when things are more silent with few people on the track. “Crackling sounds as of a furious blaze, crashing of timbers and wails as of the human voice are heard and sometimes the sounds are most frightful.”

Sleep and Dreams

Antoine Strokel (1851-1940), an Austrian runner was so sleepy during a race that he simply stopped on the track, laid down and went to sleep, causing other runners to trip over him. When awakened, he “made things lively for a few minutes.” To combat sleep deprivation, some runners, such as James Albert Cathcart (1853-1942) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, would carry a sponge soaked with ammonia and put it under their noses.

Waking up runners was a hazardous task for some of the handlers. It was said that Tom Cox, an Irishman, was one of the hardest to deal with after a nap. “He will fight like a tiger. When he is asleep, he looks like a dead man. During one match, his friends held a bogus wake over him.”

A female pedestrian, Ada Anderson would usually strike her attendants when they tried to wake her up. But like ultarunners generations after her, she perfected the art of sleepwalking around the track. She was often observed walking laps “with the step of a drunken person” watched carefully by her trainer to make sure she didn’t injure herself by running up against a railing. “Then at last, the end would come, when her frame was about to give out, suddenly she would wake up, leap into new life and bound forward around the track with the spring of a deer, her eyes bright and her mind active.”

Runner Misbehavior

Others, both runners and trainers joined in the riot. “Several spectators leaped over the railing and followed suit, and an all-round rough house ensued. The other racers were brought to a standstill and there was a general stampede on the part of spectators in other parts of the building to the scene of the fight.” The police took control and within a few minutes the runners were again going around the track. “Davis was cheered by the crowd, while jeers and catcalls were hurled at Glick, who sought refuge in his tent.” He later apologized to Davis.

In 1888, former six-day world record holder, Robert Vint (1846-1917), an Irish-American and shoemaker from Brooklyn, New York, started complaining about an unknown runner Dempsey who was dogging his tracks during a six-day race in Madison Square Garden. “Before the trainers interfered, Vint received a blow in the mouth from Dempsey’s fist, bringing blood. Vint called Demsey a name which he didn’t take kindly to.”

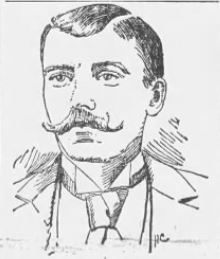

Frank Hart and John Hughes Rivalry

In 1881, several elite runners trained on a sawdust track Wood’s Gymnasium in Brooklyn, New York. Frank Hart (1856-1908), “Black Dan,” of Chicago, Illinois, the former six-day world record holder, who was black, was training there one afternoon. One of his bitter rivals, John Hughes (1850-1921),“The Lepper,” from New York City, was also on track. Hughes would often yell hate-filled racist remarks to Hart. That afternoon, Hart broke out into a strong run and Hughes ran after him. “Within a few laps, Hughes showed his superiority as a runner and passed Hart easily. ‘Never mind. I’ll beat you in the match,’ said Hart. Hughes turned around and shouted, ‘You lie, you black (n-word).’ Saying this, he struck Hart with a powerful blow under the chin. Hart fell flat on his back but was up again in an instant and hit Hughes over the right eye.” They continued to deliver blows, but Hart was no match for the bigger Hughes. Trainer Al Smith jumped in and separated them. “As Hart went away, Hughes shouted at him, ‘I’ll kill you the next time I meet you on the track.” Hughes moved his training to the American Institute building. His wife said, “He does not wish to associate longer with such low brats as frequent the Williamsburg Gymnasium.”

The two competed in the same six-day race a couple weeks later at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Unfortunately, Hart was sick from a cold from the beginning and withdrew from the six-day race after running 63 miles. “Hughes was so elated at Hart’s downfall that he vilely abused him and struck out at a lively pace.” He reached 100 miles in 16:20, but he soon lost the lead when he went off track to rest. When he returned, he was stiff. “The change in Hughes’ demeanor was marked. His stolid face had almost become a bright one when he learned of Hart’s withdrawal, but now he scowled blackly at the new leader, and all the spirit seemed to have gone out of him. He couldn’t or wouldn’t run.” He made frequent short stops on day two and experienced “excruciating pains in his stomach,” causing him to fall on the track. He eventually got up but continued to complain loudly until he quit the race after only 115 miles. “It was agreed that Hart and Hughes had allowed their personal animosity, by inciting them to an exhaustive struggle at the outset, to defeat them both. Both cried like babies and cursed their trainers, while their trainers as heartily cursed them back.”

Runners Abuse Spectators

Early during a six-day race in 1882 in England, George Cartwright (1848-1928), of Walsall, England, who had a large amount of money riding on him to win, left the track to punch a spectator who was making fun of him because he had started to slow down and walk. “The critic so riled the pedestrian that he lost his temper and endeavored to strike his annoyer who retaliated. Cartwright was struck upon the head with a bamboo stick. The blow was sufficiently violent to inflict a wound on Cartwright’s forehead and draw blood, which flowed down the competitor’s face. The police arrested the man for assault.” The British were amazed, “There must be a pleasant variety about the sport of pedestrianism which embraces pedestrianism, boxing, and ruffianism, all within the space of a few minutes.”

The most famous American pedestrian, Edward Payson Weston (1839-1929), also misbehaved at times. During a six-day race as he was reaching 360 miles, spectators were hurling offensive puns at him about his performance. “His fortitude and dashing manner however sustained him until some rash spectator remarked to a lady as he walked passed them by, ‘Weston is a good walker, but he’s got no Hart in him.” (Referring to the latest champion, Frank Hart). “The effect was almost fatal. The only effort Weston could make was to throw an orange at the band to quiet them. As soon as silence was insured on the part of the musicians, he walked into his room to recover from the shock.”

At another race in 1879, a crowd of anti-Weston spectators were hissing him every time he passed. “It annoyed him very much and he scowled and shook his cane at them. More of the crowd applauded vigorously to counteract the hisses.”

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- Evening Star (Washington, D. C.), Nov 21, 1876

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois), Jun 23, 1877

- The New Orleans Weekly Democrat (Louisiana), Mar 15, 1879

- The Selinsgrove Times-Tribune (Pennsylvania), Mar 19, 1879

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Sep 26, 1879

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Oct 16, 1879

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Feb 22, 1881

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 1, 1881

- Columbus Daily Telegram (Nebraska), Mar 26, 1891

- Birmingham Daily Post (England), Sep 26, 1882

- The Birmingham Daily Mail (England), Sep 26, 1882

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Feb 6, 1888

- The Union Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Feb 24, 1888

- The Minneapolis Times (Minnesota), Feb 8, 1891

- Altoona Tribune (Pennsylvania), Feb 24, 1891

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Mar 24, 1891

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Nov 13, 17-18, 1901

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Feb 11, 1902

- The San Francisco Call (California), Feb 11, 1902

- The New York Times (New York), Feb 14, 1902

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Feb 28, 1903

- Sun-Journal (Lewiston, Maine), Dec 29, 1906