Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:58 — 29.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

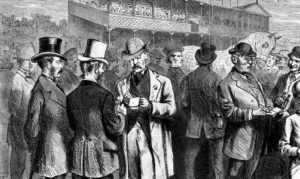

With the great success of ultrarunning (known as pedestrianism) in the 1880s, and the millions of dollars of legal wagering involved, corruption raised its ugly head in the sport. “Match Fixing,” was the most common form of corruption used. This practice made it possible for bookmakers to maximize their profits. Sports scholar Mike Huggins wrote, “The fixing of sports events has a history that is probably as old as organized sport. Persons off the field directed match fixing to make often illegal financial gains using a mixture of legal and illegal sports betting platforms, sharing some of that profit with those connected to the sport who executed the fix on the field.”

With the great success of ultrarunning (known as pedestrianism) in the 1880s, and the millions of dollars of legal wagering involved, corruption raised its ugly head in the sport. “Match Fixing,” was the most common form of corruption used. This practice made it possible for bookmakers to maximize their profits. Sports scholar Mike Huggins wrote, “The fixing of sports events has a history that is probably as old as organized sport. Persons off the field directed match fixing to make often illegal financial gains using a mixture of legal and illegal sports betting platforms, sharing some of that profit with those connected to the sport who executed the fix on the field.”

In this nineth part of the Ultrarunning Stranger Things series, some strange stories are shared about attempts to fix pedestrian matches. They are only the “tip of the iceberg” for what was taking place.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

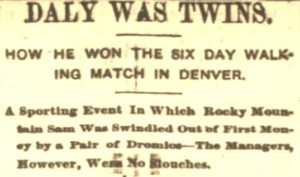

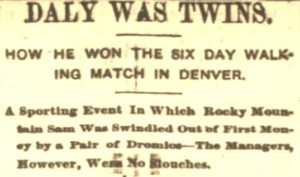

Bill Daly Runs for Six Days Without Fatigue

In 1894, a strange story was published in the Washington Post about a six-day race that occurred in 1880, in Denver, Colorado. The story was widely published and affected public opinion about the sport and the corruption involved. The six-day race was organized by Mark Montgomery Thall (1858-1901) and James Henry Love (1852-1902), celebrated agents and promoters with a firm in Denver. Previously, together they established Forester’s Theater, one of the first in Denver.

Thall was born in Montgomery, Alabama and went to California with his family in 1865. After living in Placerville for four years, he ran away from home and joined the circus at the age of eleven. He rose to become one of the best-known theatrical men in the country.

Thall and Love were referred to as “hustlers” and had been involved in organizing six-day races as early as 1879 in San Francisco where he was arrested for running off with $85 of the proceeds. The following year he went to Denver and established a theatrical business with J. H. Love called “Love, Thall & Co.”

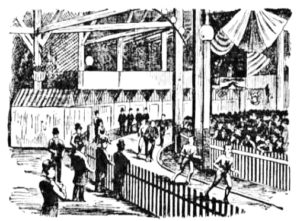

The race in Denver was held in a big tent on a track going around the edge with raised seats in the middle. About sixteen runners started including Peter Napoleon “Old Sport” Campana (1836-1906) and others. A rookie started that no one really knew – Bill Daly, who did not look very strong. Another local runner participated, “Rocky Mountain Sam” who traveled around the track with an impressive long stride. The race was popular and kept the tent full with spectators.

By day four, young Daly caught up with the leader, Rocky Mountain Sam. “The pace had been so swift that day, that Sam was all used up. His feet were swollen, and he was sick, but he kept up after Daly.” Most of the other runners had dropped out, it was a two-man race, or so they thought.

After a rest, everyone was amazed how Daly would come out so fresh, skipping around and whistling “Yankee Doodle.” Sam’s backers encouraged him and even had a brass band march along with him. On the last day, a large crowd came to watch the finish. “It got down to the last hour. Bill Daly was running easy and gaining one lap in five on poor old Sam.” In the end Daly won by over 40 miles and received a check for $3,000.

The Hoax is Discovered

It appeared that the race organizer, Thall was in on the hoax. He put on another race in Oregon with the Dalys doing the same thing and it was discovered that with the fixed win, the Daly’s split the winnings with Thall. But Thall got the last laugh when his check to the Dalys bounced.

They are lucky they didn’t try to pull this scam in England. In 1902, a trainer there sent a Leeds athlete into a race, impersonating another runner. They were discovered, arrested, and sent to prison for six months, doing hard labor.

Mark Thall died in 1901 at the young age of 41 from pneumonia. He was an owner of the Alcazar Theater in San Francisco. He left behind about $9,500, valued at about $317,000 today along with a contested $20,000 ($670,000) ownership in the Alcazar.

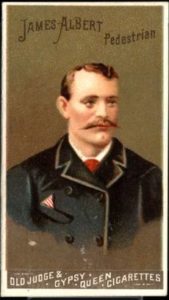

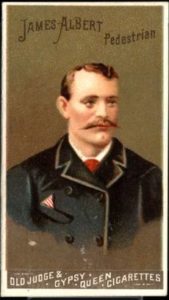

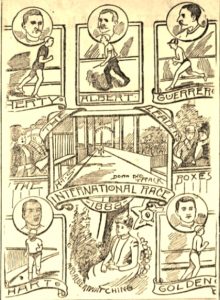

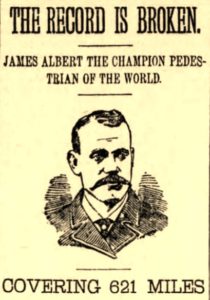

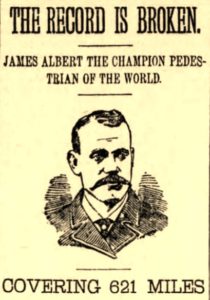

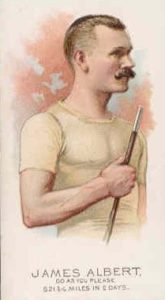

In February 1888, after James Albert of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania broke the six-day world record with 621 miles, an unsubstantiated charge surfaced that Albert had a twin brother and that they alternated times on the track. Albert denied that he had a twin, or even a brother, and his record was eventually accepted. Charles Bibbins of Omaha, Nebraska, who floated the rumor, later admitted that he was wrong.

Bribery

Bribery was a prevalent method to fix matches. Like the Black Sox scandal in baseball, runners would be bribed to throw races. It became very tempting for a runner experiencing great pain to take the easy way out to reduce that pain by accepting money and going slower or quitting altogether.

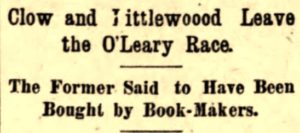

Ephraim Clow Gets Bribed

“When Clow had scored his 502 miles, he entered his cabin, and shortly afterwards emerged dressed in his everyday clothes and announced that he would walk no longer.” This was a shock because he had looked like the freshest runner on the track. “He gave various excuses, all of a flimsy character, and finally bluntly said that he would not stay in the race until $500 was placed in his hand.”

Clow left the sport, moved to Minnesota with his brothers, turned to farming and died in 1927 at the age of 72.

Old Ben Curran

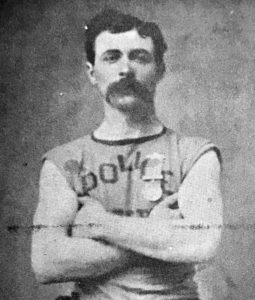

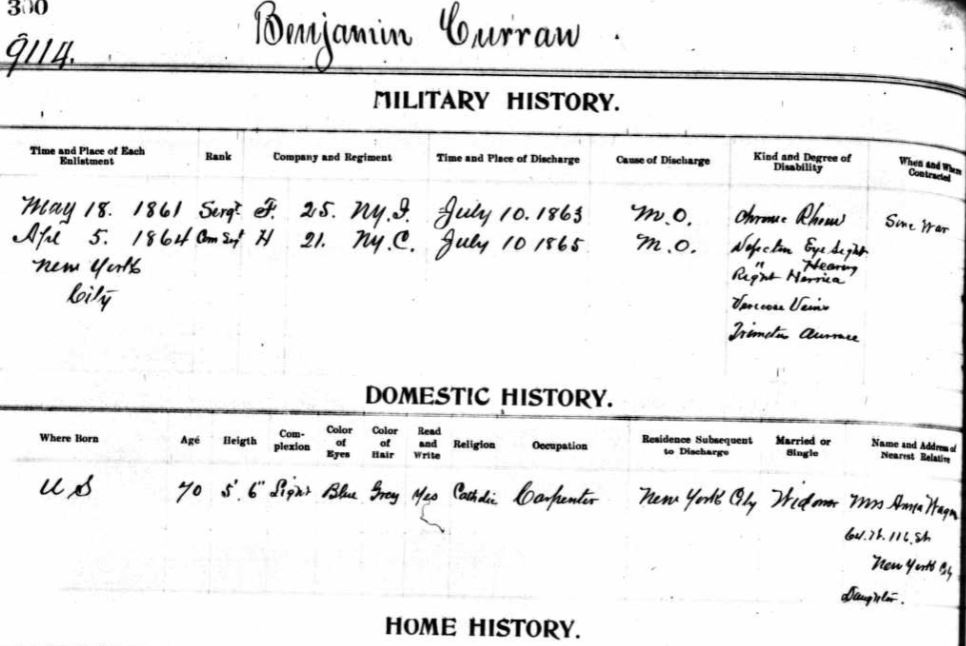

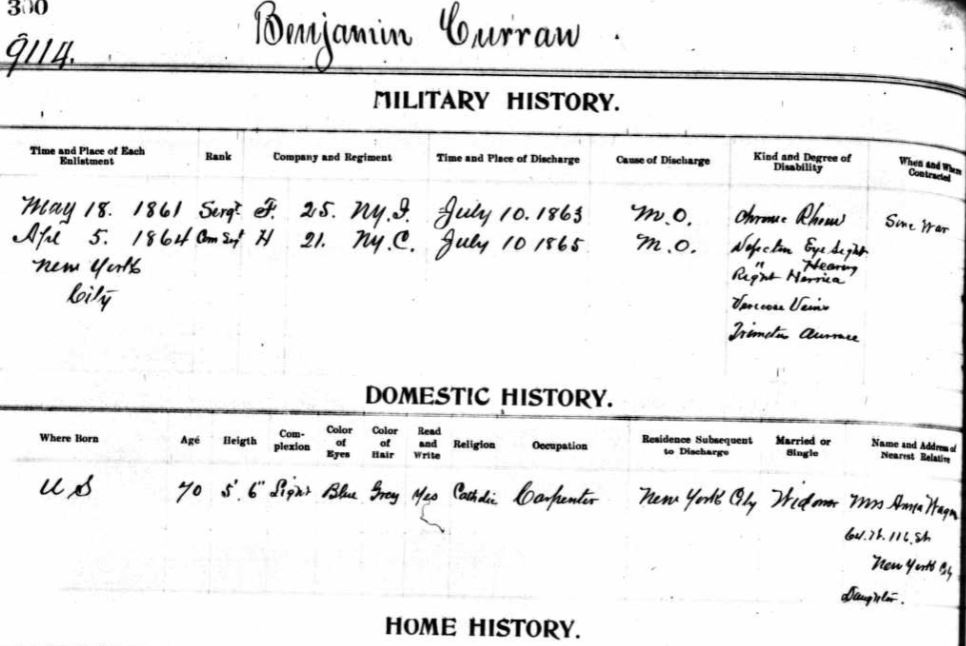

Bookmakers even tried to bribe some of the most respected runners. Benjamin Curran (1833-1907) was from New York City. He served for two years in the Civil War with the 21st Calvary and then became a longshoreman on the New York City docks. Like so many others, he tried his hand at pedestrianism in 1879 and became an instant hero of his fellow longshoremen as he achieved 428 miles in the 1st O’Leary Belt race held in October 1879 in Madison Square Garden.

Curran must not have aged well. Even though he was in his mid-40s, he was referred to as “Old Ben Curran.” In fairness, the average age of the professional pedestrian in 1879 was about 30 years old or younger compared to a modern era ultrarunning age average of about 40. But Curran must have been an aged sight. One reported said, “the ancient longshoreman looks like a member of the first Napoleon’s Old Guard.” He was described as having a “battered face, weather-beaten, that becomes more worn, day after day.”

During his first six-day competition in 1879, at the age of 46, betting odds were largely against him, because he looked so old. Spectators were stunned that such an old man could do so well pushing toward second place. “He proved himself throughout, a most persistent veteran. To all appearances he bore about his person as he walked a good many perplexing aches and pains, but he strangled these as well as he could and pushed closely for second place. His valiant march was applauded on every hand.” Curran milked the attention by overstating his age by about five years.

“Entering the cubby house that is his quarters, he would throw himself upon the bed and giving order for a change of tights, a shampoo and a shave, and sink instantly into a placid sleep. Five skilled trainers attended to his wants. Two stripped him of his boots and anointed his feet. One deftly searched out the grizzled stubble in the deep furrows of his old parchment-colored face with a razor. Another flitted about like a phantom towel-rack with numberless compartments for sponges and bottles. The renewal of the veteran completed, up he got again then, and betook himself and his pains and aches once more valorously to the track.”

Bookmakers try to Bribe Curran

In March 1881, at age 47, Curran again competed for the O’Leary Belt in Madison Square Garden. He was a fan favorite because people thought he was so elderly. “The old man’s legs are gnarled and twisted like the limb of an oak, but they have done him better service than anybody ever expected they would.” The press was critical having such an old man in the race. “There is nothing to be hoped for by the friends of Ben Curran, as his aged frame and inelastic limbs can scarcely stand the present strain put upon them. A man of his years would be better employed working at his legitimate daily labor than competing with younger men in a contest that demands youth and elasticity.”

Large wagers had been made that the runner Dick Lacouse, of Boston Massachusetts, would finish in second or third place. However, Curran was performing so well, twelve miles ahead, that he was disrupting these wagers. Lacouse’s backers boldly approached Curran to give up third place for $1,500 worth of wager tickets. “Unfortunately for the longshoreman’s reputation, he accepted the $1,500 bribe.”

When the race manager, James E. Kelly (1832-1903), heard of it, he immediately wanted to stamp out the corruption going on. He saw the tickets in Curran’s hut and Curran said he was used up and quitting. Kelly threatened to bring in the reporters to witness a doctor declaring that Curran was perfectly able to continue running. “If Curran cared to be exposed, he could accept the bribe. Curran decided that he wouldn’t leave the track and Mr. Kelly then gave him a new $500 bill.” He then stuck the bill on the end of his walking stick as a signal to those who knew that he had declined to be bribed, that the $500 was a “reward for Roman virtue.”

The spectators were confused, so Kelly went to the reporter’s stand and said, “I do not wish this to be misconstrued. I have paid this $500 out of my own pocket as I do not wish injustice done.” It is interesting to note that Kelly’s business, “Kelly & Bliss” was a bookmaking firm that also operated pool rooms and horse racetrack betting. He had been a pioneer in American legal bookmaking that was brought from England in about 1873. But he was indicted at times for illegal activities. Yes, bookmakers were even putting on pedestrian events. Curan indeed finished in third place with an impressive 504 miles. Lacouse finished with 489 miles in fourth.

In 1892, Curran, applied for a military pension as a Civil War invalid veteran at the age of 59. Ten years later he was in a home for disabled veterans. He died in 1907 at the age of 74.

Daniel Burns Bribed

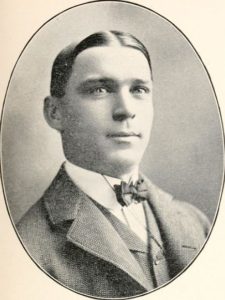

Daniel D. Burns (1860-), from Elmira, New York, came into the sport in 1879 as a 19-year-old newsboy. He gained great fame for allegedly walking a horse to death during a race in Chicago in 1880 where he reached 578 miles in 6.5 days. He raced in many other six-day races and placed well against some of the best in the world.

In Atlanta, Georgia, in May 1885, a three-day walking match was held. Burns, age 25, was doing well and expected to win. But he started to fade which worried his chief backer, John Thompson, who had wagered $1,000 on Burns to win. To try to help incentivize Burns, he paid him $150 to push harder.

But in this 1885 race, he started to fade which worried his chief backer, John Thompson, who had wagered $1,000 on Burns to win. To try to help incentivize Burns, he paid him $150 to push harder. But later, Burns also took a $350 bribe to lose the race. He was seen lagging behind even though he looked fresh. After he lost, Thompson investigated, and the truth of the bribe came out. “Burns and his trainer Brooks were both arrested and taken to the calaboose, still in their skin-tight suits. Friends of the arrested men protested that the men would die if kept in such a place after three days walking and a guard was detailed to watch them at their rooms at a boarding house, but later they were taken to prison.”

You would think that Burns would be run out of the sport, but no. A few months later he was competing again. He ran many races in his hometown of Elmira, New York. He became a well-respected proprietor of the Columbia Hotel in Elmira.

For his last seven years he worked as a bartender at a hotel in Binghamton, New York. He and his wife had seven children. He died in 1914 at the age of 53. His obituary remembered his pedestrian feats. “Mr. Burns’ favorite racing was the go-as-you-please race. He was often matched against the most famous racers of their day.”

James Albert Offered Bribe

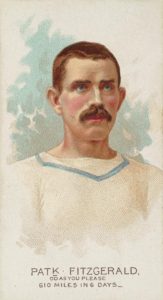

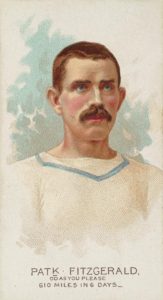

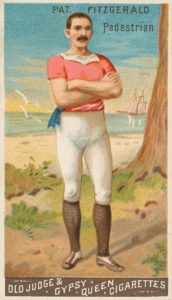

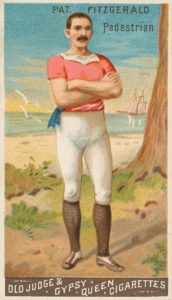

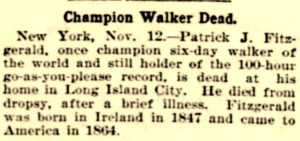

After Albert had reached an amazing 545 miles on day five, he knew that breaking Patrick Fitzgerald’s 610-mile world record was within reach. Bookmakers were distressed because they had offered such high odds at the beginning of the race on bets to those who thought the world record would be broken. They were in danger of losing a fortune.

Stories circulated that gamblers were going to try to poison Albert’s food or cripple him in some way. “But Albert’s good-looking wife watched closely over her husband and the only chance they had left to prevent record-breaking was to buy off the record breakers.”

Sure enough, Albert was approached with bribes to stop short of the world record. He said, “I was told that there was $10,000 waiting for me if I kept under 610 miles. They argued that this would be nearly double what I would receive from the race, but as I was not in the market, I declined the proposition.” He passed over a dollar amount that today is valued at $312,000. Mrs. Albert added, “They were bothering me too. I was asked to persuade him to take the biggest money and let the little go. But we want to leave this race with a good reputation and Jim won’t take anything.”

Policemen were placed on guard, but the bribers used unknown men to get into quarters used by the trainers and the runners. Efforts were made to forcibly remove Albert from the track, but those didn’t work. “Fourteen policemen were watching him, prepared to arrest the first individual who should make the slightest hostile demonstration.”

Albert Breaks the World Record

Albert returned to New York expressing the opinion that something about California caused “weakness attacks to the legs” and that new world records could not be broken there. “It is an unprofitable country for pedestrians, but the promised land for boxers.”

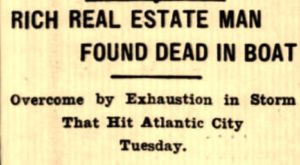

After a couple more years, Albert finally retired from running. During his career, he invested his winnings wisely in real estate in Atlantic City, and by 1889 it was valued at $50,000 (or $1.5 million). He became very wealthy and developed the famed boardwalk area, funding the construction of a 1,200-foot iron pier out into the ocean that included a dancing hall.

Trainer is Bribed

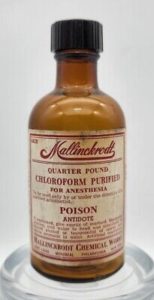

Lacouse explained about the drugging. “The first dose was administered a few hours before the race started on the pretense that it would settle his stomach. He alleged that his trainer used chloroform or physic mixed with ginger ale purposely to make him unfit for the track throughout the race.” He said, “I covered 489 miles, yet was compelled to be off the track in all 54 hours, almost twice as much as any other man, so I feel confident that I was good for second if not first place.” On day four, the trainer took him off the track and gave him something that “seemed to set his frame on fire” causing him to become feverish. Was it true, or just an excuse? He finished in fourth place.

Rumors of Trainer Bribed

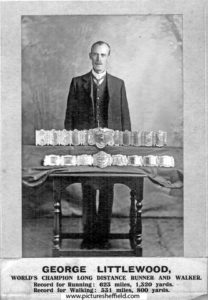

In 1884, Fitzgerald was determined to get the six-day world record back. During the late stages, he believed his highly experienced and respected trainer, “Happy Jack” Smith, of being bribed to drug him. Smith’s real name was John D. Oliver (1862-1914), of Boston Massachusetts. He had been a successful boxer. When pedestrianism took off, he trained and handled many the top American ultrarunners of his era and was the most famous trainer of that time.

Fitzgerald used his riches to establish a training park, athletic hall, hotel, and a saloon in the Ravenswood neighborhood of Long Island (Queens). He died in 1900 of dropsy at the age of 55.

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- Mike Huggins, “Match-fixing: a historical perspective.”

- Reading Times (Pennsylvania), May 13, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Oct 11, 1879

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Nov 24, 1879

- Sacramento Bee (California), Jan 17, 1880

- The New York Times (New York), Jan 24, Mar 6, 1881, May 4, 1884

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 6, 20, May 28, 1881, Feb 12, 1888, Dec 4, 1891, Nov 27, 1914

- Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock, Arkansas), May 28, 1881

- The Macon Telegraph (Georgia), May 5, 1885

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), May 4, 1885

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), May 4, 1885

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Feb 8, 1888

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Feb 12, 1888

- The Sun (New York, New York), Sep 5, 1883, Feb 12, 1888

- Waterbury Evening Democrat (Connecticut), Feb 23, 1888

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Apr 22, 1889

- The Daily Courier (San Bernardino, California), May 16, 1889

- The Yonkers Herald (New York), Aug 22, 1894

- Asbury Park Press (New Jersey), Nov 5, 1898

- The Evening Mail (Stockton, California), Oct 14, 1901

- Evening Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California) Oct 9, 1902

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Feb 14, 1903

- Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), May 13, 1914