Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:07 — 32.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

Fannie Edwards’ Love Triangle

In 1879, Fannie Edwards (1856-) of New York City, born in Portland Maine, burst onto the stage of pedestrianism when she succeeded in walking 3,000 quarter miles in 3,000 quarter hours at Brewster Hall in New York City on March 20, 1879.

But along with her fame came scandal. She became quickly involved in a love triangle. She had been seen in public with Frank Leonardson for several months in the New York City area. Frank, also a pedestrian, was described as very good looking. He served as her trainer during her successful month-long walk. Fannie was described as “quite young, below the medium height and of slight 100 pounds, almost fragile physique. She has large lustrous brown eyes, an abundance of dark hair, and well-rounded features, suffused with the glow of health.”

The judge ruled that Frank must pay his wife $200 and pay $3 per week for alimony. “Fannie screamed, ‘Is that all?’ with delight and surprise. She then bounded, brushed past Mrs. Lenardsen, and offered her gold watch and chain, her necklace, bracelets, and earrings to the court as security to have Frank released.” The judge said, “The court is not a pawn shop for lovers.” She then wrote out a check for the $200 and $156 for a year of support, and said, “That’s cheap enough, I’d pay a thousand dollars to be rid of her.” Delia was left in a corner of the courtroom “crying as if her heart would break.” Frank and Fannie Edwards went off together. To get away from the scandal, they went to California to compete.

Fannie Edwards Destroys Another Marriage

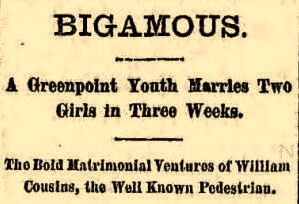

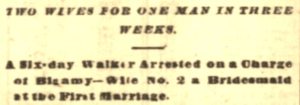

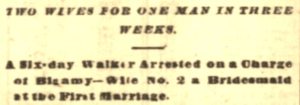

Fannie Edwards was not through destroying marriages. William A. Cousins (1858-1880), of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York, who was called “a well-known pedestrian” was arrested on November 18, 1880, in Brooklyn for having two wives. He was described “a well-built young man, of 22 or 23 years, and of rough exterior.” (It is interesting to point out that even though Cousins called himself “a champion pedestrian,” no successful pedestrian accomplishments have been found for him.) He was the son of a machinist and his younger brother Hiram, had recently died in a tragic fire at a box factory.

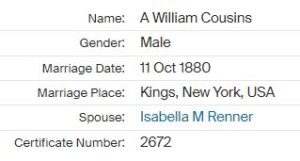

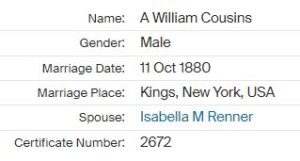

Cousins married Isabella M. Remer on October 11, 1880. She was quote “a handsome blonde of eighteen.” Isabella had known Cousins for a year and on her wedding day, he brought Fannie Edwards to her mother’s house, announcing that he had selected her to be a bridesmaid. “He explained that Miss Edwards being a pedestrienne, he made her acquaintance in a professional way.” But after only four days of marriage, because of serious arguments between the two, Cousins deserted Isabella and sought to marry Edwards.

Isabella said, “The next week, he came to see me and asked to see the certificate of marriage, which as soon as I gave it into his hand he tore up and burned. He then said that that ended our marriage and that I need not trouble myself any further about him, as he was going to marry Miss Edwards. He then went away. I was astonished, but I could do nothing.”

On his next visit to Isabella, he brought Edwards and let her know that they were engaged to be married. Isabella said she was his lawful wife and that she would fix him if he married again. She said, “He threatened to knock me down and kill me if I interfered with him in any way. Miss Edwards heard all and simply said that our marriage was of no account now that the certificate was torn up, and that she would marry Cousins anyway, as she was more suitable for him. He again threatened my life if I troubled him and went away with Miss Edwards.”

The two pedestrians married about three weeks after Cousins’ first marriage, on November 2, 1880. He then visited Isabella again, laughed and threatened Isabella some more. But she was determined to see him arrested. With some detective work, she found the reverend that had married the two and obtained a warrant for Cousins’ arrest. Cousins was arrested, couldn’t pay the $1,000 bail, and was held in jail until the trial.

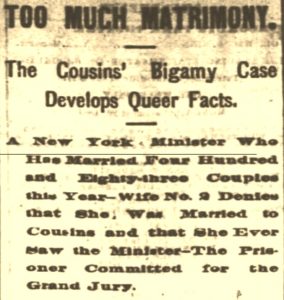

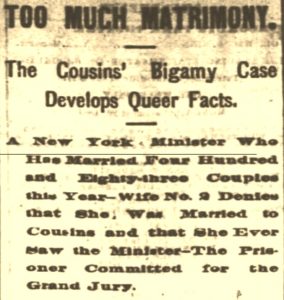

At the trial, Reverend Francis Joseph Schneider (1832-1903 ) a pastor without a church, known as “the marrying parson,” testified that he remembered marrying Cousins and Edwards. Edwards testified that her real name was Frances Alvina Wurms. She denied that she had been married to Cousins and had never seen the Reverend before. She had lived as a boarder at Cousins’ house for two months. She was then caught in several lies, even denying that she had been known as Fannie Edwards. She denied ever meeting Isabella and that she wasn’t the bridesmaid at their wedding. Witnesses and a marriage certificate showed that Edwards’ testimony was full of lies.

Mary Marshall’s Love Triangle

Getting romantically involved with trainers seemed to happen often. Mary/May Marshall (1841-1911) was one of the most famous and successful female pedestrians of the 19th Century. Her career was discussed in episode 101 and 102. Marshall’s true name was Tryphena (Curtis) Lipsey. She was married to Thomas Lipsey. After they moved to Chicago, they experienced financial trouble which motivated her to try pedestrianism in 1875, taking on the stage name of Mary Marshall.

After experiencing great pedestrian success and being away from her family during long road trips, in 1877, Marshall, still married and age 36, got romantically involved with the 23-year-old pedestrian George F. Avery (1854-1885) of Maine and Massachusetts, who called himself, “P.T. Barnam’s Great Pedestrian.” (See episode 94). He had been Marshall’s trainer and they became romantically involved. But to Marshall’s dismay, Avery soon left her for the much younger pedestrian Bertha “Bertie” LeFranc (1859-) originally from Paris France, who was only 18 years old. Her true name was Matilda Colom. The scandal went public because Avery walked out with LeFranc while Marshall was competing in Massachusetts. She was left without her trainer and failed in her walking efforts. The scandal resulted in the breakup of Marshall’s marriage to Thomas Lipsey. Her husband and son moved to Iowa. Avery and LeFranc married and about a year later she gave birth to a girl. Avery worked as LeFranc’s trainer.

Marshall changed her public name to “May Marshall,” but then stopped competing for a time because she was with child and gave birth to Stonewall Lipsey (1878-1963) (He later was known as Allen Stonewall Curtis, raised by Marshall’s family). She returned to competition in 1878, giving the excuse that she had been away because of yellow fever, evidently trying to keep the birth a secret. In 1882 she married pedestrian, Harry Hager. She continued to perform for several years in various publicity stunts, including races against skaters and people pushing wheelbarrows, and died in 1911.

A common question in the family had always been whether her son Stonewall Lipsey was a product of Marshall’s marriage, or of her affair with Avery. Marshall’s great-great-grandson solved the mystery with a DNA test, confirming that he was also a descendant of the pedestrian George F. Avery who died in 1884 of heart disease.

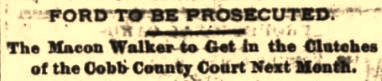

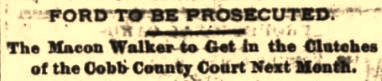

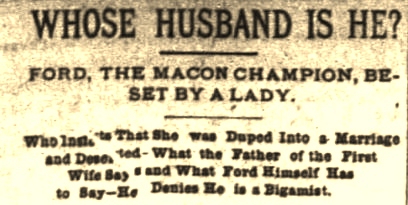

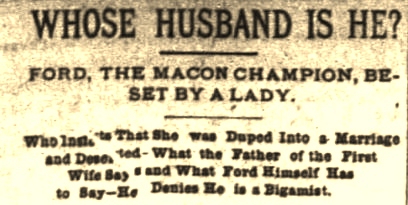

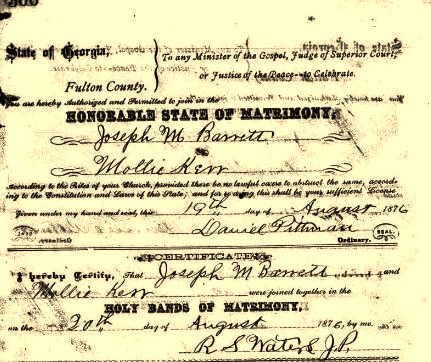

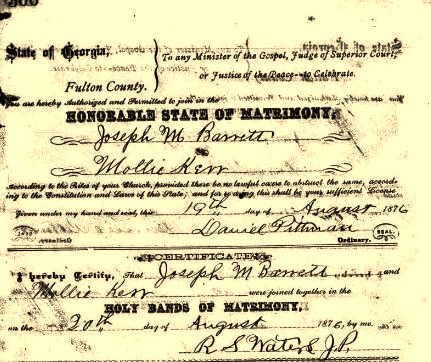

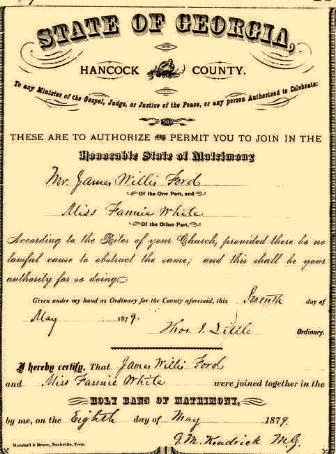

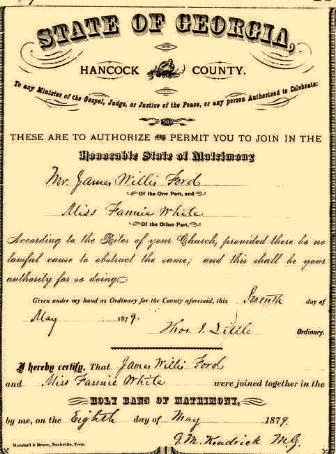

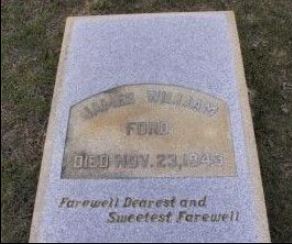

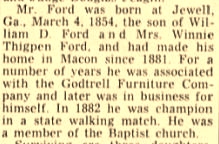

James W. Ford had Two Wives

During the race, “it was said that as he passed a certain point on the track, a lady with a pleasant face, but plainly attired was observed to lean forward and whisper words to the champion.” Ford was noticeably startled but kept up his pace. When he came by again, the lady said, “you shall be arrested before 9:00.” Ford went to his tent, followed by the lady and he soon quit the race, claiming that he had taken ill.

According to Ford, he and Mollie left the race together and returned home. Mollie expressed her love for him, but knew he didn’t really love her, so still demanded that he pay her so she could get a divorce. He accused her of being married to another person too. Finally, he agreed to give her the money for their divorce and then left, hoping to never see her again.

Mollie did not let it rest there. The public was hungry for more details about this strange scandal. Mollie was summoned to appear before the county grand jury to indict Ford for bigamy. It was rumored that she knew Ford had another wife when they got married. It is presumed that Ford’s defense lawyers would claim that he was drugged when they married.

Next, the reporter interviewed Jabez M White (1839-1908), the father of Ford’s first wife. He claimed that Ford and his daughter, Francis “Fannie” Augustus White (1861-1931) had been married for six years. He had suspected that Ford was being unfaithful with Mollie, went to see her, and found out that she was also married to Ford. He told the shocking news to his daughter. She wrote to Ford and essentially told him to get lost. Jabez White said, “The next train brought him to Atlanta and when he entered the house about sunrise, I got up and hunted for my pistol to kill him, but my wife had hidden it. I then had Ford arrested. My daughter went almost crazy, and her physician said if I did not release Ford, she would lose her mind.” White decided to drop the charges, but his daughter remained ill.

No report was found to indicate that the bigamy trial was ever held. Ford returned to his first wife, Fannie, and they moved to Macon, Georgia. About three years later in 1887, he returned to Atlanta for a quick visit and again was arrested, due to a warrant issued by a furniture dealer, J. W. Hinman, who had been waiting for a chance to force Ford to pay him $75 that he said was owed to him. He got an arrest warrant to be issued for bigamy and theft.

Ford turned himself in, determined to fight the bigamy charge. Mollie Kerr refused to testify in court. She had completely back peddled on the claim that they were ever married. In a letter, she stated “If Ford and herself were ever married that they were drinking at the time, and she knew nothing of it.” She wrote that the complainant, Hinman, had previously approached her about a plan to blackmail Ford. Interesting enough, the letter was witnessed by a Miss A. P. Prater, likely Prater’s sister, strengthening the idea that their Molie and the Prater may have conspired to get Ford to quit that race. Ford settled the case by paying $70 to Hinman and court costs. Hinman withdrew the warrant.

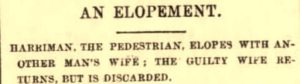

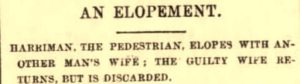

Charles Harriman Runs Off with a Man’s Wife

In 1879, Charles A. Harriman (1853-1919), age 25, a shoemaker, was originally from Maine but living in Haverhill, Massachusetts. At the age of fifteen, he ran away from home and enlisted in the Navy, where he served for several years. He returned home and went to work in a shoe shop. When he was about 20 years old the shop owner challenged him to a foot race in Auburn, Maine. Harriman won, and that started his love to run.

By 1879, his ultradistance experience was recent, but impressive, breaking the existing walking 100-mile world record with a time of 18:48:40. With no six-day experience, he entered the Third Astley Belt six-day race in New York City and was accepted.

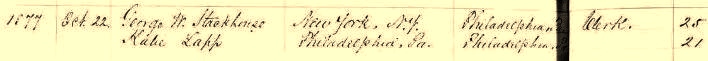

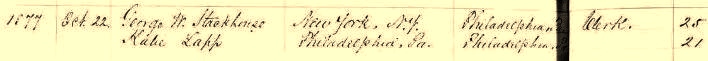

A week before the race, Harriman trained in Central Park and stayed at the St. James Hotel where he flirted with Katie (Lapp) Stackhouse (1856-), the beautiful wife of the St James hotel steward, George W. Stackhouse (1852-). She was described as “a handsome brunette of about 22 years of age.”

During the March 1879, race the very tall Harriman was a fan favorite among the women and received many bouquets of flowers from them. Katie was among his most enthusiastic admirers and would go each day to watch him run, “casting bewitching glances,” and she gave him a large basket of flowers. For his final day, she made him a red, white, and blue sash which he wore around his waist. He ended up placing third with 450 miles, winning $3,679, valued at $105,000 today.

After finishing his race, Harriman had to be carried to a carriage back to the St. James Hotel. A day after, his eyes were still bloodshot, but he looked well and was being well cared for by Katie. “She carried dainties to the weary pedestrian and relieved the heavy hours by reading to him. It is said that by these means a tender feeling sprang up in the bosoms of both.”

In July 1879, Katie went to visit her parents in Philadelphia, but went missing after a few days. Katie ran off to join Harriman in Richmond, Virginia where Harriman was competing. Her husband hired a private detective to track her down. She was finally found with Harriman in Medford, Massachusetts. They had been staying together at the Eagle House Hotel and she registered as Katie Wilson. They were seen several times together in public. They took a ride on the steamer General Bartlett. “The lady was dressed in the height of fashion. Her dress had a long trail, her gloves had fourteen buttons, her bracelets were large, and she wore a ring with seven diamonds. She dined with her gloves on.”

Stackhouse filed for divorce and also filed a suit against Harriman for $10,000. Stackhouse was successful in freezing Harriman’s bank account. Once Katie learned that the scandal went public, and that Harriman couldn’t spend his money, she returned home and begged to be forgiven and taken back by her husband. She also wanted Harriman’s money freed up. Stackhouse refused to accept her back. “Mrs. Stackhouse on her knees again implored forgiveness and again was denied. Finding her husband obdurate, she left.” He sold all her belongings, including her piano. “Stackhouse started out armed with a six-shooter and determined to perforate the amorous pedestrian as soon as he could discover his whereabouts.”

![]()

![]()

He returned to Maine in 1897 and a few years later organized a labor union for lime kiln workers in Rockland, Maine. Into his late 50s, he put on walking exhibitions. Late in life he became an evangelist pastor. He died on March 14, 1919, at the age of 66, of Bright’s Disease and was survived by a second wife and five children.

Elsa Von Blumen

During this exhibition, trouble brewed. The wife of her manager/trainer, Burt Miller, became very jealous of the attention that her husband was giving to Von Blumen. Mrs. Miller’s mother seemed to be at the root of the problem. “She made Miller’s wife jealous, and basely slandered Miss Von Blumen and circulated false stories about her.”

The result was a very public “grand old row” among them that created great excitement among the citizens of the city. It was reported, “The manager’s wife and Miss Von Blumen became reconciled the next morning. The Miss Von Blumen seems to have the sympathy of our citizens, and no imputation against her character are intimated. It is an unfortunate affair all around, as the entertainment was drawing full houses and giving good satisfaction.” Von Blumen finished her 100-miles as promised.

John W. Jackson

The two were taken to jail and while there, news came that a girl named Emma Martin had attempted suicide by taking strychnine. “She was found in an unconscious state, but the doctors say she will recover. A note was found by her bedside addressed to Jackson, saying she could not live without him and wanting to die. A trial was held and the case against Jackson and Gillespie was dismissed.

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- Harry Hall, The Pedestriennes: America’s Forgotten Superstars

- The Norfolk Virginian (Virginia), Apr 1, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jul 14, 1879, May 7, 1884, Mar 15, 1919

- Louis Globe (Missouri), Jul 14, 1879

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Jul 15, 1879

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C), Jul 15, Oct 20, 1879

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Jul 23, 1879

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Nov 19, 1880

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Nov 18, 1880, Jan 21, 1881

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Feb 6, Nov 29, 1880

- The Sun (New York), Mar 20, 1881

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 28, 1879, Jun 28, 1884

- Tulare County Times (Visalia, California), May 17, 1879

- The Highland Weekly News (Hillsboro, Ohio), Jul 3, 17, 1879

- Fayette County Herald (Washington, Ohio), Jul 17, 1879

- The Evening Mail (Stockton, California), Dec 14, 1880

- The Times-Democrat (Lima, Ohio), Apr 22, 1880

- The Spirit of the Times (New York, New York), Feb 16, 1884

- Savannah Morning News (Georgia), Jun 26, 1884

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), Jul 10, 26, 1884

- The Macon Telegraph (Georgia), Jan 13, 1887

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Feb 3, 1889

- The Dayton Herald (Ohio), Feb 2, 7, 1889

- Sun-Journal (Lewiston, Maine), Jan 8, 1907

- The York Dispatch (Pennsylvania), Jun 6, 1935