Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:53 — 28.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Run Davy Crockett’s Pony Express Trail 50 or 100-miler to be held on October 14-15, 2022, on the historic wild west Pony Express Trail in Utah. Run among the wild horses. Crew required. Your family and friends drive along with you. http://ponyexpress100.org/ |

Runners Accused of Becoming Insane

In some cases, runners acted so irrationally that they were declared insane and committed to institutions.

John Gowan

In the morning he started walking again, but his eyes grew wild and staring, and he let out a wild-west war whoop. “His trainer squeezed a sponge soaked in water and ammonia in his face. Gowan struck his trainer in the face and made a bolt for the Madison Avenue end of the Garden.” He cleared the fence of the track in one leap. “Then the fellow rushed wildly down the paved lobby, cleared the brass railing at the ticket box, and ran out into Madison Square Garden arrayed in all the glory of dirty tights and a bright bule silk jumper. Two policemen gave chase and caught the escaped pedestrian. Bringing him back, the officers lifted him bodily over the rail, and his trainers led him back to his hut and put him to bed. A moment later one of them opened the door to take a peep at the fatigue-crazed pedestrian and Gowan plumped him a singing blow in the face.”

His friends next took him to a room in Putnam House and locked him in. But he escaped through a window and down a fire escape. “Upon reaching the street he sped down 4th Avenue in quicker time than was ever made on the tanbark. At this point he was spied by an officer. When the officer tried to arrest the man, he fought like a tiger and finally assistance had to be called. He was taken to the police precinct and thence in an ambulance to Bellevue hospital.”

It was concluded that his illness was caused by a lack of nourishment. The trainers were accused of giving Gowan so much whisky that it would have knocked out a man. It was believed that he had gone insane. A few days later, he had recovered. “A short rest was all that was needed to restore his mind.” His sister commented that he had not been fit for the severe mental or physical effort demanded by a six-day race. He retired from the sport.

Ultrarunning Fans Committed

![]()

![]()

In 1892, in Reading Pennsylvania, another walking woman was thought to be insane and taken to the state asylums. “She is crazy on walking. For years she read everything she could get about walking matches until she became convinced that she was dominated by the spirits of O’Leary, Rowell, Weston and other great walkers. Whenever she could escape from the house she would go away on a long walk, sometimes not appearing again for days, during which time she would tramp hundreds of miles. Within a year she extended one of her tramps as far as Chicago.”

In 1879, in New York City, strange reports came into the police about a man running down Flatbush Avenue, creating intense fright among some. The man would move out of the way of carriages, but still continue fast. Police officer Hawxhurst took up the chase. Finally, the man was stopped by a night watchman and taken into custody. “He was fairly dripping with perspiration and looked like a man who had just been fished out of the water. His breathing came fast, and he evidently was in a much exhausted condition.” When questioned he pleaded to be allowed to “finish the race.” He was taken to the police station but continued to plunge up and down in an approved pedestrian style. They figured out that “the poor fellow is a hopeless victim of the walking mania, and even when he was put into the cell, he continued to make lap after lap around the narrow circuit.” A doctor suggested they take the prisoner from his cell and be allowed to walk in the yard in the fresh air. The man walked and run for three hours until exhausted then carried back to his cell to sleep for the night. In the morning he awoke and asked to be put on the track. His friends were notified to come and get him.

Former Ultrarunners Never Fully Recover

There were several cases where former pedestrians later experienced some mental illness and their families believed that it had been caused by their ultrarunning. James Noon of Cliffwood, New Jersey, was one such athlete for competed in a six-day race. Several years later in 1903, he was taken to the State Asylum at Trenton, New Jersey, blaming his condition on the effects of that race.

In 1891, in Chicago, John S. Dobler, a former very accomplished professional six-day pedestrian, who had once held the world record for six days limited to 12 hours per day, had been delivering mail for the post office. “Recently he began carrying away everything that attracted his attention in the stores where he left mail. He was declared insane by Judge Scales and was sent to an asylum.” In Dobler’s room were found stolen bottles of cologne, brandy, cigars, and rolls of cloth.

Millie Rose suffered terribly during a race due to taking all sorts of “stimulating fluids including beer and brandy.” She collapsed on the track and during her next match experienced an epileptic seizer while on the track. She was bedridden for the next several months and her abusive husband had her declared insane, left her, and took all her money. Thankfully, she eventually recovered, competed again, and had her husband arrested.

In 1877, people in Princeton, Illinois, believed that walking in a 24-hour match ruined Carrie Parker’s life and drove her to insanity. She had become “a raving maniac” and was brought before a court. “Her father testified that ever since the walking match his daughter had been suffering with great nervous prostration and recently, she suddenly conceived of the idea that her whole body was charged with electricity, and she would not touch her feet to the floor.” She was sent to an asylum.

Health Scares

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

There were plenty of other heath scares experienced by the runners. Gus Guerrero experienced bleeding from his lungs which scared him. After 400 miles, elite runner Peter Panchot fell on his face from exhaustion and came out with a bruised and cut face. In 1888, John Dillon, a railroad baggage master, of New York City, was running in a six-day race in Madison Square Garden and only needed 20 more miles to earn a lucrative share of the gate money. Several friends had brought the longshoreman a generous supply of “Jersey Lightning” which he drank too freely. Later on, he stopped on the track and refused to go on. Three of his competitors tried to help and took his arms, making him walk with them. But finally, he bolted off the track and refused to go on. He surprisingly withdrew and did not qualify for the huge payday.

Deaths

As professional pedestrianism became more popular, health experts of the era believed that these ultrarunners were severely impacting their life expectancy. “Pedestrian contests have done much harm and any man who makes a practice of six-day walks cannot live to old age, because the strains wasted the nervous and muscular tissues.” Also, “Physicians agree that these protracted strains upon walkers’ system shorten their lives. It is the excess of the exercise that is dangerous.” They of course had no data to back their guesses. In reality, the greats Edward Payson Weston and Daniel O’Leary lived into their 80s and 90s, far longer than the normal life expectancy of that era.

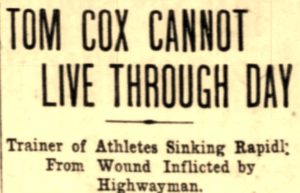

![]()

![]()

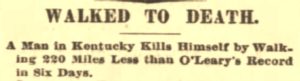

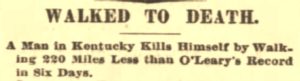

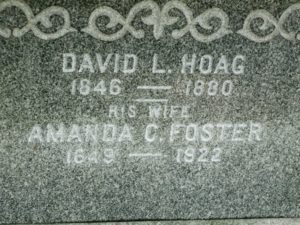

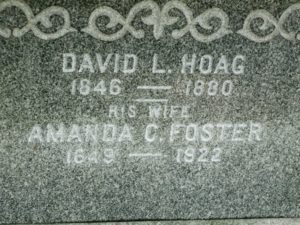

The trainer, Richard H. Nichols was arrested for manslaughter, although the grand jury would be asked to indict him on first degree murder. “Hoag became so exhausted by over-exertion and improper care and ill treatment on the track and neglect after that race that he expired.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Two young men of Newburgh, New York died and were said to have walked into their graves. Elijah Van Keuren was very active in walking early matches around New York City. “When he began, he enjoyed excellent health, but after walking awhile he began to fail, and then rapidly fell into hasty consumption (tuberculosis) and died.” James “Hoppy” Crawford, age 23, successfully walked 100 miles in 24 miles. “After completing the task, he was as perfect wreck. Crawford died of consumption after lingering for several months.”

In 1879, Clarence G. Howard (1859-1879), a twenty-year-old young man, a laborer in a brick yard, who had taken part in various long-distance pedestrian matched on Long Island and Brooklyn, New York, died at his home on Long Island, “from prostration caused by excessive exercise.” He is buried in Huntington Rural Cemetery.

Suicides

Sadly, a pattern of suicides afflicted many of these ultrarunners of the 1800s. There were likely many reasons, but it was common for successful runners to pile up a fortune of winnings, only to see it gone within a few years due to wild spending, gambling, or from being swindled. Health issues were also a factor.

In 1881, Joseph Allen (1846-1881), age 35, a very accomplished six-day pedestrian who once walked 525 miles in Madison Square Garden, but failed in his last race, was found dead on a road near North Adams, Massachusetts. “The physician’s verdict was heart disease, although a man of his description jumped from a railroad train late Monday night at a point where his body was found. Allen participated in the last three six-day go-as-you-please pedestrian contests in New York City. He leaves a wife and several children in Adams, where he made his home since coming from Carlisle, England.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Sad Story of Mattie Potts

Potts was described as blonde, tall and bony. “She wears a jaunty white straw hat, trimmed with blue ribbon, a short black walking dress and store shoes. She explains that she thirsts for glory.” She kept notes as she journeyed and hoped to write a book. She generally walked on railroads and sent her luggage ahead down the line. Somehow, she found time and energy to put on paid walking exhibitions in evenings along the way. Curiously, she sometimes arrived in towns on a train. She complained about towns that would charge her for meals.

Potts said in Alabama she had trouble with a train. “A gravel train backed upon her while she was on a bridge and she jumped on an iron bridge support and swung herself over the water and hung there.” Along the way she had eleven proposals for marriage.

In her pocket was found a note that included, “I am about to do a rash act, which I hope the world will forgive me doing. It is nearly five weeks since I returned to Philadelphia. I was in debt for one week’s board and I was politely told by the proprietor that I could stay no longer.” She tried to get employment but rejected over and over again. She concluded, “I want my body given to the medical students in Philadelphia. I am perfectly sane, but I have nothing to live on nor nothing to live for. So good-bye to the world.”

She was locked up for the night at the police station because attempting suicide at that time was a crime. “Whenever the long, shrill whistle of the trains speeding by near the police station were heard, the woman started up and begged to be let out that she might go and throw herself under the locomotive.”

The judge was smart and believed that she wasn’t really a suicide threat, that she was just trying to generate sympathy and publicity. A well-known lady took interest in her and started to collect donations for her.

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- P. S. Marshall, King of Peds

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois), Jun 23, 1877

- The Stark County Democrat (Canton, Ohio), Nov 14, 1878

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Mar 4, 1879

- Chicago Tribune, Apr 4, May 23, 1879

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Apr 15, Sep 23, Nov 1-15. 1879

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Oct 8, 1879

- Selma Dollar Times (Alabama), Oct 15, 1879

- Richmond Dispatch (Virginia), Nov 14, 1879

- Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 1, 1880

- Burlington Free Press (Vermont), April 1, 1880

- New York Tribune (New York), Apr 15, 1880

- The Valley Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), Jul 16, 1880

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), May 28, 1883

- The Macon Telegraph (Georgia), Sep 24. 1884

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Feb 8, 1888

- The Evening Mail (Stockton, California), May 19, 1888

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Feb 23, 1891

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Mar 19, 1891

- The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York), Mar 19, 1891

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), May 13, 1879, Mar 22, 1880, Mar 20, 1891

- Interstate News-Record (Ironwood, Michigan), Apr 18, 1891

- St. Louise Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Mar 31, 1892

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), Apr 25, 1895

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Nov 14, 1879, Mar 14, 1902

- The Indianapolis Star (Indiana), Aug 26, 1903

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Nov 10, 1902, Feb 10, 1908

- The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), Mar 19, 1908