Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:13 — 31.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Also, this opinion expressed in the New York Herald was common, “A six-day walking match is a more brutal exhibition than a prize fight or a gladiatorial contest. In the last half of a six-day walk, nearly every contestant is vacant minded or literally crazy, he becomes an unreasoning animal, whom his keepers find sometimes sullen, sometimes savage, but never sensible.” During this era from 1875-1909, at least 400 six-day races were competed worldwide with millions of paid spectators. The stranger things that occurred related to the sport of that age were a collection of surprises and tragedies.

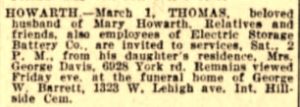

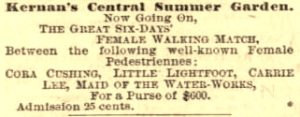

John Dermody Joins a Women’s Six-day Race

In December 1879, John Dermody, age 45, was a homeless lemon peddler in Brooklyn, New York. The six-day race ultrarunning/pedestrian fever was raging in America. He believed that his business had hardened his leg muscles with great strength and that he would make an excellent professional pedestrian, and he longed to compete in one of the dozens of races that were being held in the New York City area that year.

Dermody could not find anyone to back him financially and help him pay an entrance fee to a race. A Women’s International Six-Day Tournament was scheduled for December 15-20, 1879, in Madison Square Garden with 26 entrants. As it approached, Dermody became so interested in it that he had been unable to think or talk of anything else.

On the Sunday afternoon before the start, Dermody entered the Darwin & Kindelon saloon at 507 Third Avenue, drinking perhaps too much and jabbering about the sport of walking, wishing that he could see the start of the women’s tournament. Darwin, a known practical joker, asked Dermody how he would like to enter this contest. “Dermody seemed perfectly delighted. His acceptance of the proposition was hailed by some practical jokers as a good chance for amusement, and they at once began to improvise a female wardrobe which would conceal his sex. His flowing reddish beard was shaved off in a neighboring barber shop, and he was dressed in a calico skirt and spotted jacket.”

They added a pair of long stockings, a handkerchief around his head, a blue veil around his neck, and three yards of white gauze to make a sash to hide his face. They made a bib number with “32” to be suspended from his neck. Ready to go, his new backers took him to Madison Square Garden where the race was about to start.

Out on the Track

![]()

![]()

Arrest

The next day he was arraigned at the Jefferson Market Police Court with the charge of being intoxicated. He was still wearing his costume from the previous evening. “When Sergeant Keating told his story, the stranger’s real character was afforded by a person in the court, who, it appears, was responsible for the masquerade in pursuance of a practical joke.”

Justice Bixby, probably laughing, decided that Dermody had been sufficiently punished and set him free. He went off “at an orthodox pedestrian pace,” probably still happy that he had been able to participate in a pedestrian race.

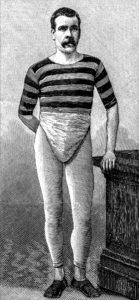

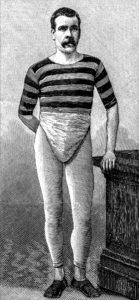

George Cartwright – Scoundrel

In February 1880, at the age of 32, Cartwright ran in his first multi-day race, a seven-day contest in Nottingham, England, six hours per day and won with 270 miles. Seven months later, in September 1880, he competed in a major six-day, 12-hours per day race in London, at the massive Agricultural Hall. There were 29 starters, and he went out fast with the more experienced front-runners, reaching 76 miles in the first 12 hours. But after day two, he quit the race after reaching 138 miles with a foot injury. He healed up and continued to compete in six-day, six hours per day races for the next couple of years.

Arrested for Deserting his Family

But then Cartwright got into legal trouble. On April 24, 1882, he started in a six-day race for the Astley Championship Belt held at Drill Hall in Sheffield, England with 25 starters. As usual, he went out very fast, cheered by 2,000 spectators. He finished the first 12-hour day in the lead with 76 miles.

On the third day, he fell well behind the leaders, and he decided to quit the race. As he started his journey to his room at midnight, an officer arrested him. The warrant charged him for deserting his wife and five children who became wards of the Lichfield Guardians. News reports of the race helped authorities locate him. “He was taken to a police cell instead of to the comfortable training quarters to which he had been no doubt looking forward after his pedestrian exertions.”

Instead of showing concern and going to help his family, when he was brought before the court, he instead wanted to pay the costs incurred by the Guardians, so that he could stay in Sheffield. The court stated that they had no authority to accept his payoff money, and assigned an officer to take him to Lichfield, Staffordshire, England. 70 miles away, to be dealt with. Evidently, he settled the complaint and just two weeks later was again racing in Dundee, Scotland, far from his family, in a 26-hour race which he quit after 71 miles due to a sore ankle.

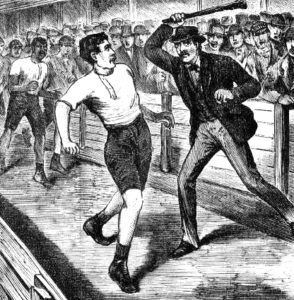

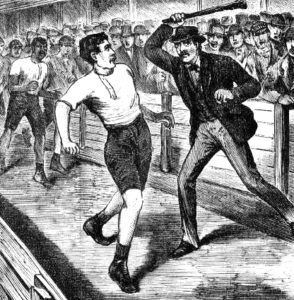

Cartwright Attacked During Race

Over the next few years, Cartwright established himself as one of the best six-day pedestrians in the world, achieving a personal best of 570 miles at Sharonen, England. During that race he reached an astonishing 152 miles on the first day. If true, it was a world record for 24-hours. On February 23, 1887, he broke the 50-mile world record at Westminster Aquarium in London with an amazing time of 5:55:04. That mark would stand for decades.

To America

With all his success in Great Britain, it was time for Cartwright to take his talents to America. He sailed for America on January 4, 1888, on the steamship Ohio to compete in the Six Day’s International Go-as-you-please Race at Madison Square Garden on February 6-11, 1888. After a two-week ocean voyage, he arrived in New York City. He was brash in his predictions. “Records don’t frighten me. Anybody who beats me in this race will have to beat 625 miles.” The current world record for six days was 610 miles, held by Patrick Fitzgerald of Long Island City, New York.

After competing in a couple more races, he returned to England to take care of some business but then quickly returned to America for an extended stay on the steamship Servia. “On the journey, he took practice runs three times a day on the deck of the steamer. An eight-lap to a mile track was measured off and some days he covered as much as 45 miles. His work was watched with interest by other passengers.” He was anxious to establish himself firmly as the champion of England, hoping to beat the new sensation, young George Littlewood. Cartwright went into training on Staten Island for another six-day race at Madison Square Garden.

Cartwright in Trouble Again

Once the heat was off, Cartwright returned to America about a month later, apparently with his wife, with plans to stay. He claimed that he was looking for the man who originated what he said was the false story about his attempted marriage. But he quickly resumed racing in California, far away from Saratoga, New York. In June 1889, it was reported that he was suffering from malaria, staying with his wife in New York City.

On June 29, 1901, at the age of 52, Cartwright became a U.S. citizen at Syracuse, New York and lived out his years there. He died sometime after 1925.

Weary Pedestrian Shot his Wife

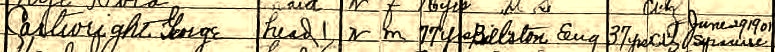

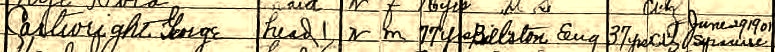

![]()

![]()

On November 20, 1850, a week after completing his walking task, he and his wife, Mary, a seamstress, went into the pub Jamaica Vaults. He ordered a beer for himself and some whiskey for his wife. “In his hand, he held a pistol, with which he said he would blow someone’s brains out before he slept that night. The boy who served the liquor asked him for payment, upon which Harriett said he would shoot the boy if he said another word.”

His poor wife was rushed to the hospital, and it was necessary to amputate two of her fingers. She was in serious condition. When police interrogated Harriett, he told them about his weary 1,100 miles that he had recently walked. He had bought the pistol from the landlord of Strawberry Gardens that was used to shoot off during the night to wake him up each hour. “Since completing his pedestrian feat, whenever he got any drink, he did not know what he was doing, and as to his wife and children, he loved them most dearly. He then wept bitterly and was committed for trial.” His wife remained in the hospital for many days.

At the trial, he defended himself and couldn’t understand how it happened, that he could not remember that night. The jury returned a verdict of guilt, but strongly recommended mercy for him. The judge said he wasn’t surprised that the great exertion of his walk, and the lack of rest caused Harriett to experience “considerable nervous excitement and irritability.” Combined with the vice of intoxication, it produced a most brutalizing effect on him. But that didn’t excuse him for his actions. He was sentenced to prison with hard labor for nine months.

Race with a Wooden Leg

Pedestrian’s Wife Burned to Death

Tragedies that came into the lives of these famous pedestrians were often noted in the newspapers.

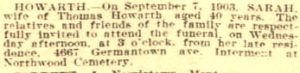

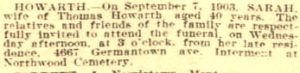

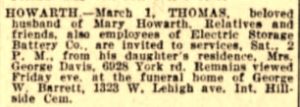

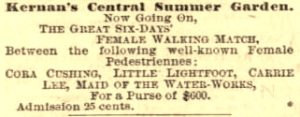

Thomas Howarth (1860-1932) was from Lancashire, England. He started running at the age of 12 when he ran a mile in less than six minutes. A few years later he emigrated to America to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a runner, not a walker. He set an American record for 25 miles, with 2:41 and clocked 50 miles in 6:21. He started participating in six-day races in 1887 and quickly progressed to be one of the top pedestrians in America and was thought to be the youngest runner to reach over 500 miles. During the later 1800s, he competed in at least 23 six-day races and regularly won them. In 1891 he retired and raised some of the finest game cocks in the country and was involved in cock fighting.

Howarth had married Sarah in 1889 and they had a daughter Gertrude. But in 1903, the Howarths became separated. On September 7, 1903, tragedy struck. “About 4:00 in the afternoon, Sarah retired to her room. Fifteen minutes later Policemen Wright and Lint, who were watching a ball game on a lot close by, saw smoke issuing from the second story windows of the Elser Street dwelling. Hurrying to investigate, they learned that the smoke was coming from the room occupied by Mrs. Howarth. The door of the apartment was quickly forced and the woman was found lying on the bed dead.”

A Mother’s Tragedy

Mother Tries to get Daughter to Stop

The Brooklyn Citizen wrote, “It is difficult to see what great magnet of attraction a woman can see in such a line of amusement, but there remains still a possibility that ere the six days are over, the obstreperous miss may be only too glad to seek the shelter of her home and there rest her weary body and aching joints, probably with a full sense of her own folly impressed on her weakened intellect.”

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Nov 1, 8, 1850

- The Guardian (London, England), Nov 9, 1850

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Nov 22, 1850

- The Morning Chronicle (London, England), Dec 16, 1850

- The North Alabamian (Tuscumbia, Alabama), Sep 5, 1879.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Dec 15, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 15, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Dec 16, 1879

- Sheffield Independent (England), Apr 25, 1882

- Manchester Evening News (England), Apr 27, 1882

- Sheffield Independent (England), Apr 28, 1882

- Dundee Advertiser (Scotland), May 15, 1882

- Illustrated Police News (London, England), Oct 7, 1882

- The Leavenworth Standard (Kansas), May 1, 1884

- York Herald (England), Jan 7, 1888

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 11, Dec 8, 1888

- The Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky), Apr 16, 1888

- The New York Times (New York), Apr 17, 1888

- Chicago Tribune, (Illinois) May 7, 1888

- The Post-Star, (Glens Falls, New York), Sep 25, 1888

- Fall River Daily Evening News (Massachusetts), Dec 7, 1888

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Dec 7, 1888, Jun 29, 1889

- The Times Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Dec 10, 1888

- The Record-Union (Sacramento, California), Dec 7, 1888, Mar 29, 1889

- Toronto Daily Mail (Ontario, Canada), Jan 18, 1889

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), May 11, 1893

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Feb 9, 1897

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Sep 8, 1903