Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:03 — 30.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

The sport of ultrarunning during the 19th century was truly filled with tales of strange things that are unthinkable and shocking to us today. This is the first part of more than ten true surprising articles/episodes taken from 19th century newspapers about wild tales that took place in the sport of ultrarunning/pedestrianism This episode will present two bizarre and shocking stories that have never been fully told and have been forgotten — the Van Ness shooting, and the head-scratching story of John Owen Snyder, “The Indiana Walking Wonder,” who may have walked and run more miles in three years than anyone in history.

| Subscribe to the Ultrarunning History Podcast to get alerts and downloads automatically when new episodes are published every two weeks: https://ultrarunninghistory.com/subscribe-to-podcast/ |

Peter Van Ness

Peter Lewis Van Ness (1853-1900) was from Brooklyn, New York. He began his famed professional pedestrian career in 1876 when he started to walk six-day matches against women, reaching 450 miles. He was about six-feet tall and was known to plod along in “rakish style” and a strange gait, wearing striped stockings up to his knees. He had walked in several six-day races and had success in 50-mile races.

The 1,000 Mile Match Begins

Everything started out well during the first week. Both started to complain of calloused heels and Van Ness suffered from headaches. But both looked well and didn’t show signs of exhaustion. “Van Ness walks with a free and easy movement of his whole body, keeping a sharp eye on his opponent and laughing and talking with friends in the room. His walk is strongly suggestive of a hungry man on his way to dinner.” His fastest half-mile was clocked in 4:20.

![]()

![]()

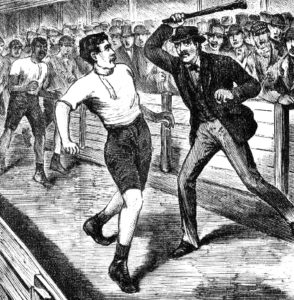

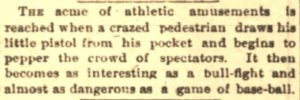

Van Ness Parties

On March 3, 1879, after Van Ness had covered about 859 miles in 36 days, everything went bad for Van Ness. Many of his friends from Brooklyn came to watch his performance and during his rest spells would join him in his room to drink. “The pedestrian joined them in their carousal. He drank freely of port wine and became hilarious.” Out on the track in his drunkenness, he entertained about 50 people with “some rapid walking and occasionally peculiar fancy steps, as if he were balancing himself on a giddy trapeze.”

A bell rang when he reached his half mile, and he went back to his room to party with his friends. Finally, completely drunk at 8:30 p.m., his friends were forced to leave by his handlers. For unknown reasons, one of his friends presented him with a gift of a revolver which was loaded. Van Ness then fell into a deep sleep.

Shots Are Fired

“When the moment came for him to be called to go upon the track, his trainer, Joseph Burgoine, undertook the task of getting him out of bed. But Van Ness was sound asleep, and it required physical force to awaken him. He protested against the operation and became violent and abusive.” Burgoine was forceful and insisted the Van Ness return to the track. His ankles and legs were badly swollen, and he complained about a burning sensation in his throat and brain.

Woman pedestrian rising star, 17-year-old, Amy Howard, (1862-1885) of Brooklyn, who had just put on a walking exhibition in the hall was in the women’s dressing room next door. Hearing the shots, the women in the room screamed. A bullet was later found in the wall of that room. “Howard declared that the bullet went almost near enough to her head to scorch her frizzes.”

The Show Must Go On

With so many dollars of wagers on the line, the show must go on. “Hot drops” were administered to the crazy pedestrian, and shortly thereafter Van Ness was brought back on the track and resumed his task at after 9:00 p.m.” Most of the spectators, fearing they would be shot, had left the building.

Marketing Hoax?

The Boston Post speculated, “It is supposed the whole affair was an advertising dodge.” Given the printed evidence and conflicting strange versions of the story, it is possible that the Boston Post was correct. But contemporaries seemed to mostly believe the incident was true. The shot in the arm was only a flesh wound. On March 10, 1879, Van Ness successfully completed his 2,000 half miles in about 2,000 half hours. It is pretty clear that he missed at least one-half hour during the incident.

Two weeks later Van Ness raced against John Colston at Eagle Hall in Hoboken, New Jersey. But during the evening he quit, claiming that he received a telegram that his brother, Schuyler was dying in Brooklyn. “The visitors of the hall denounced the affair as a fraud.” His brother must have recovered because he did not die until 1908. Van Ness did not accomplish any further significant pedestrian accomplishments and he soon disappeared from the sport. He died of a heart attack in 1900 while playing cards with his family. “Peter Van Ness suddenly fell from his chair and died in a few minutes. He was in the best of health and had been laughing and joking over the game of cards.”

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

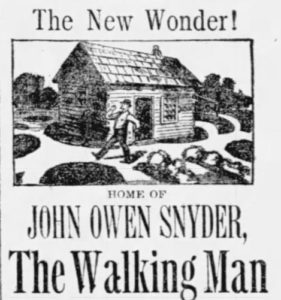

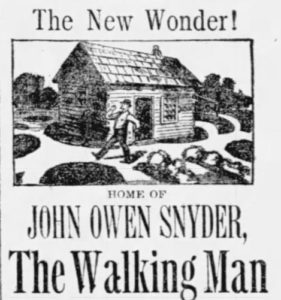

The Strange Indiana Walking Wonder

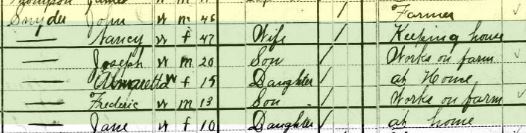

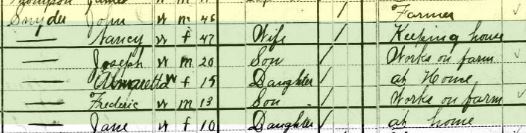

Snyder was married with five children and lived on a small remote farm a few miles from any town. While working in the harvest fields with his sons on October 24, 1884, a feeling attacked his arms that was terribly painful. He discovered that the relief only came when he did vigorous exercise. He said, “I wanted to use my arms all the time. I had to keep ‘em in motion. I chopped wood in the day and at night I would grab a broom and scrub all night.”

Walking Begins

In six weeks, the disease shifted to his hips and legs, requiring him to walk to find relief. “I could not stand still. I had to keep moving. I used to go slow at first. I couldn’t sit down. My legs would get cold and pain me. Then I got to going pretty fast and then it got me running.”

It seemed like three layers had mysteriously formed on the soles of his feet. He believed that the only way to remove them would be through walking. “He at once took up the line of march in the rear of his dwelling on his farm, walking in a circle.” His friends and neighbors tried to get him to stop but failed in their efforts. His doctor tried to convince him that the problem was in his head, not his feet and legs.

Efforts to Cure Snyder

A religious evangelist came one day to cure him. Snyder said, “He went down upon his knees and prayed so long and loud that it made me tired. He said I had no faith. I told him to go over to a neighbor and cure a poor fellow afflicted with cancer and then call again, and I would have more faith. He never returned.”

Early on, he was sent to an asylum and continued to walk while under mental care. “When restrained from walking, his feet alternately would lift from the ground. He said that if he would stop walking, his limbs and body would fly into a thousand fragments.” He was released from the hospital and declared mentally sane, harmless, but afflicted by a rare brain disease. He continued to walk.

Nationwide Publicity

About nine months later, in August 1885, the first of many news stories was published nation-wide about Snyder, over-estimating that he had walked 16,000 miles so far. “He walks around a small ring near his house in all kinds of weather, eating as he walks and stopping only when too tired to go any longer. Then he drops into a chair and sleeps a few hours, and immediately resumes his walk. He has not lain down since he was attacked by this peculiar mania.”

In cold weather he walked in his small home in a room reserved for his walking. While inside, he felt like a prisoner but would accelerate his pace until he “fairly runs about his apartment.” He wore broad, heavy-soled shoes, without socks, and the muscles and tendons of his legs were as tense and firm as rawhide. Oddly, he never became sick. His digestion was good and temperature, circulation and respiration normal.

Even more strangely, he seemed to have a gift to foretell coming events. Many events occurred that he predicted accurately. In 1885, he talked about a great world war that would happen in a few decades, but also predicted that the world would soon end as the sun cooled. “He never jests or laughs, nor whistles, but will talk to all who visit him and is clear and lucid on all points except the cause of his desire to walk. He is of a quiet disposition, unless aroused by some insinuation that he is a crank or monomaniac; then he is someway violent and demonstrative.”

After more than a year of this, he believed it would take 50,000 miles to cure him of his malady. But after believing he exceeded that distance, he kept it going

Hundreds Come to Witness

A month later, during the cold December of 1886, a reporter described his home, an old three-room log cabin. “In front and on either side of the cabin are narrow foot-paths, worn deep into the earth and made hard almost as rock by constant travel.” He went into the house and found Snyder marching around a wood-burning stove. The walker enjoyed telling the story of his sad affliction.

In two years, he had worn out ten pairs of heavy shoes and twice that number of soles and had walked an estimated 59,000 miles. He had been married for 30 years and two of his adult sons cultivated the farm and provided support for the family. Three daughters helped with duties in the home. He felt confident that at some time he would overcome the disease.

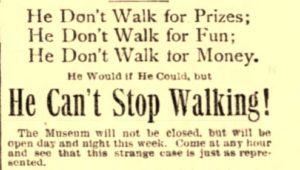

Exhibitions in Museums

While in Chicago the odd feeling went from his legs to the soles of his feet and he had hope that he was finally walking out of it, but the weather changed, and the pain went back up in his legs again. He explained what it felt like. “It is a kind of tickling pain. It goes first up one side of my leg and then down the other and feels more like a bug or something crawling up and down your legs more than anything else.”

He moved his show on to Indianapolis. More than 10,000 people would come to Eden Musee to watch him walk during a week. He then walked at various fairs in Indiana. But after nine months, he stopped his tour once an impostor started appearing in cities. He put a stop to the fraud and vowed to never appear in public again. His appearances netted him about $12,000 (worth $370,000 in today’s value). The fortune allowed him to expand his farm to 50 acres and make his family comfortable.

Snyder’s Final Months of Walking

During the Fall of 1887, Snyder became ill and started to get steadily weaker. His legs began to swell, making him walk with a limp. “It was a sad scene that met the eye of this reporter. With feeble, tottering steps, and a face upon which was stamped suffering and melancholy.” When asked if he would ever stop walking he replied, “I am afraid not in this world. In the next, dunno.”

He soon became pale and haggard and at times refused to talk. It was evident that he was slowly dying. When visited in early November, he said, “I feel I am nearing the end of my journey.” A week earlier he rejoiced when he thought the end had come when he became blind and felt faint, but he revived and continued on. He said he still averaged walking about 20 miles per day. He said he was feeling lonesome and sad at times. “I fear I may die, and none be near me to know how I die or assist me if I need help. I wish to die while walking about. My three years’ affliction has warmed my heart towards all mankind.”

But still he walked on. “he says the only relief he can obtain is in keeping in motion. To stop means suicide, to stop means death, and a terrible death. To stop, the legs and feet cramp until the torture is beyond endurance in its intensity.”

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Jan 28, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Feb 2, 10, Mar 24, 1879

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Jan 18, May 1, 1887, Feb 15, 1879

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Feb 24, 1879

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Feb 24, 1879

- The Sun (New York City, New York), Mar 4, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 4, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 4, 1879

- The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), Aug 19, 1885

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Aug 7, 1885, Dec 18, 1885

- Winfield Daily Courier (Kansas), Feb 17, 1886

- The Post-Star (Glens Falls, New York), Jul 8, 1886

- The Indianapolis Journal (Indiana), Nov 23, Dec 12, 1886, Apr 10-11, Jul 28, 1887

- The Muncie Morning News (Indiana), Jan 8, 1887

- The Dayton Herald (Ohio), Jan 21, 1887

- The Fort Wayne Sentinel (Indiana), Mar 21, 1887

- The Indianapolis Journal (Indiana), Apr 17, 1887

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Oct 29, 1887

- The Jasper Weekly Courier (Indiana), Nov 11, 1887

- The Advance (Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin) Dec 12, 1887

- The Huntington Democrat (Indiana), Dec 15, 1887

- The News (Quincy, Illinois), Dec 6, 1887

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 6, 1887

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 7, 1887

- Manitoba Weekly Free Press (Winnipeg, Canada), Dec 8, 1887

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Apr 15, 1900