Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:58 — 25.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

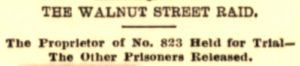

Race Accused of Disorderly Conduct in a Saloon

Jamison, who also had a retail store, had previous run-ins with the law and believed the raid “was a piece of spite work on the part of a neighbor with whom he was competing in business.” At the hearing, it was testified that the place was noisy and disorderly. “Mr. J. L. Grotenthaler, the owner of the competing business, said the place was interfering with his business, and he was losing his lady customers. Officer Watson said that he visited the place because of complaints that young girls were enticed into it. He saw a man guarding the entrance to the show room allowing nobody to enter without one of the checks presented by the barkeeper with each glass of beer or liquor sold. He saw both men and women drinking. Jamison was held for $1,000 to answer the charge of keeping a disorderly house and the other prisoners were released.”

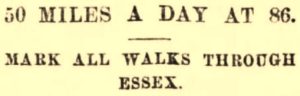

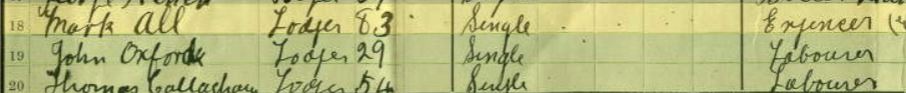

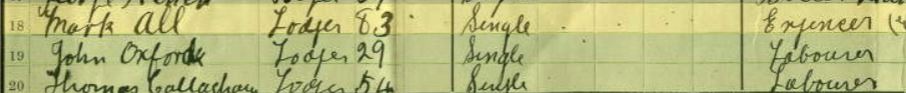

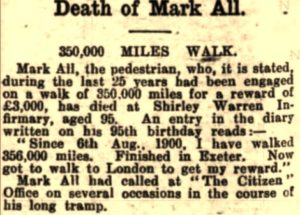

Mark All, the 60,000-mile Pedestrian Arrested

All was born in Greenwich, England in 1828 where he learned an electrical engineering career. For years he was employed by a firm of engineers. But during a great strike of 1897-98, he lost his employment. Since he was 72 years old, he made up his mind to start a walking tour and find employment wherever he could, to prove that a man isn’t “used up” in old age.

All claimed that he started a long walk on August 6, 1900, and walked 30,000 miles before his efforts were noticed by the sports newspapers of that era in 1904. He said that three of the papers raised a £500 prize for him if he could continue and reach 60,000 miles in a total of seven years. He was described as “a ruddy-faced, white-haired man, carrying a black bag containing small engineering tools, a walking stick and having a picture of his dead British bulldog suspended from a button of his waistcoat.”

His tales to reporters became more and more outlandish. “Mr. All has suffered as many persecutions as St. Paul, been flung into prison, attacked with knives, shot at, stoned, baited with dogs, and had many adventures and extraordinary escapes.”

Starting in 1909, authorities finally recognized that he was a homeless traveling tramp, and he was committed or admitted voluntarily over and over again to workhouses. These were public assistance institutions and were intended to provide temporary accommodation for homeless people. They would do work such as digging for potatoes.

All would state to reporters that there were important conditions for his walk, “that he shall not enter a workhouse or fall into the hands of police.” Well, records show, he was committed to workhouses continually. He would get out and visit local newspaper offices, claiming that his walk was continuing, with a trip even to America. Reports never saw him walking, he was only seen in newspaper offices.

As All was nearing death, he stated that he hoped that in the afterlife he “may travel on a beautiful highway where there will be no bloomin’ motor cars to choke an old fellow with dust.”

The Tax Man Cometh

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Signup at https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Assault with a Pewter Pot

In 1881, George Pegge (1830-1884), age 51, a shoemaker from Derby, England, “a well-known pedestrian” who had recently walked 102 miles in 25 hours and accomplished 382 miles in a six-day match, was charged with a violent assault on a butcher, Henry Thorpe. “On Monday, Pegge entered the Old Neptune Inn and offered to walk against anybody to the town of Burton for £20. He then offered some money to Thorpe telling him to cover the bet, but when he declined, pushed it away and the money fell on the floor. Pegge gave him a blow on the head with a pewter pot, injuring him severely, and saying he would knock his brains out. The tankard hit Thorpe’s head, cut the scalp, and caused a wound which had to be dressed at the Infirmary.” Pegge was sentenced to three months in prison with hard labor. He had been convicted of other crimes before, including stealing a hare from a neighbor. He had been called a “foolish, drunken freak.”

Cruelty to Children

In 1881, in New York City, Thomas Smith Sr. was arrested for cruelty to children. At the American Institute Building, he forced his 15-year-old son, Thomas Smith Jr., to participate in a walking match, “in which, after having walked 98 miles under the use of stimulants and influences, the boy fell insensible on the track, completely broken down.” The father made him continue, supporting him as he tottered around the track. But when that didn’t work, he carried his son to his tent, and then he was sent home in a carriage “in a dangerous condition.” At the trial, the boy denied that he had been forced to compete, but Smith pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to ten days in prison and given a $100 fine.

Wife Beater

In 1881, Michael S. Tynan, a shoemaker from Staten Island, New York, competed in the 3rd O’Leary Belt six-day race in Madison Square Garden. He left the track after reaching 85 miles in the first 24 hours. His friends had pressured him into entering the race and he went home with a feeling of disgust about failing. He took it out on his wife, Alice, and beat her, giving her black eyes and tearing out much of her hair. “It was shown that Mr. Tynan was of irritable temper, especially at times when he was in training, and that it was customary for him to throw dishes around the house, break glass and raise the wind generally. He promised to reform before leaving the court, and marched down Butler Street followed by two of his misguided backers in the recent contest.” He was fined $20 which was paid by his employer.

Runner Charged with Sexual Assault

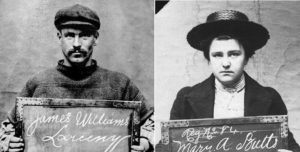

Arrested for Stealing

In 1887, Thomas Trainor, a former professional pedestrian, was wanted for stealing a diamond ring from Thomas Kirk. He was spotted on the streets of Pittsburgh by police and a foot chase was conducted. “But being too fleet-footed for the policeman, he would have escaped had not he been headed off by two other officers.”

Getting proper footwear was important to runners. John Green, a former professional pedestrian was boarding with Thomas White in Eastleigh, England in 1887. One day White noticed that Green was wearing a pair of boots and socks that had been stolen from his house. He refused to return them, and White had Green arrested. At the trial, it came out that the boots, valued at 11 shillings, had been in a box with other things that the landlady had taken from White in lieu of rent and she had given them to Green. “She said White owed her money, and she detained his box, which after a time she broke open and amongst other things were the boots and socks which she lent to Green.” White dropped the charges, but when investigators looked more closely, it turned out that the boots were military property White was then charged with unlawful possession and proof was found that he had purchased them from Winchester Barracks. He ended up getting a heavy fine for obtaining the articles.

Arrested for Highway Robbery

Robertson has been visiting him in jail and affectionate interviews have taken place between the two.” She brought a clergyman with her to the jail, stating that she was going to marry Davis at once and that she wanted to share his cell with him. The Sheriff would not allow the marriage until permission was granted by her parents. The young woman wept terribly, knowing that permission would not come. After two months in jail, Davis was acquitted of all charges. It is unknown if the marriage took place.

Arrested for Drunkenness

It was fairly common for pedestrians to become alcoholics, given the amount of liquor that many of them drank during training and races. In 1883, the English champion, George Hazael (1845-1911) from London, England, was in New York City to try to win money racing others and to establish a pub in the city. He said, “I am prepared to run anybody in the world from ten miles to 100 miles. I don’t think there will be any more six-day races. There is no money in them. I have run three times more races than any other man. I am well-fixed in regard to finances, and never felt better in my life.”

He was soon arrested along with three others in Brooklyn, New York, for drunkenness. “They were found squabbling with a hackman near Broadway and Hazael accused one of them of stealing a buffalo robe, but it was shown that it was dragged off the back in the squabble.”

Sunday Lawbreakers

Many cities had laws against holding events on Sundays. In 1879, as six-day races were reaching their height in New York City, the Brooklyn chief of police, Patrick Campbell (1827-1908) received complaints about walking matches being held on Sundays at Mozart Garden. The police chief went to see Mayor James Howell (1829-1997), believing that there was a law on the books against the practice and he wondered about the permit that the mayor had issued for the race. The mayor assured the chief that he had not thought about the Sunday problem. “He believed that men should go to church and that the day should be observed according to Christian custom. If such a place as Mozart Garden were kept open on Sunday by virtue of his permission, he wished to revoke the permit.” Thus, in Brooklyn, the mayor started to disallow races on Sundays.

They found an obscure law on the books. “There was no statue in the State on the subject except one, which imposes a fine on a man if he is out walking anywhere on Sunday, unless it be in pursuit of charity, going after medicine or the doctor, or is on his way to church if the church is within a distance of twenty miles.” They also found an ordinance against rope-dancing, an exhibition of animals, puppet shows, or other common shows without a permit signed by the mayor.” It was clear that they needed to pass a specific law against pedestrianism on Sundays and they intended to pursue it.

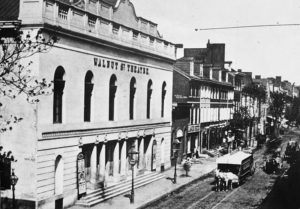

The mayor pulled the permit for the current female walking match at Mozart Garden. The justification was, “these physical shows on Sundays have become a nuisance to Brooklyn that residents in the neighborhood are annoyed by them and that adjacent property is depreciated; that the whole thing is foreign to the traditions and habits of Brooklyn; that crowds of idle and loud tonged loiterers are gathered inside and outside the building by them, to the great annoyance of quiet and orderly families who pass on their way to and from church.”

Brooklyn took a hard stance and published that week, “Sunday pedestrianism in a public hall to which the public is admitted will not in the future be tolerated in Brooklyn. The morals of the community and the peacefulness of the city on Sunday are of more importance than any ‘sacrifice of calves’ on the part of any number of pedestrians.”

Later that same year, six women were competing in a six-day match at Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. “Two were arrested at night for violation of the Sunday law. The others escaped.”

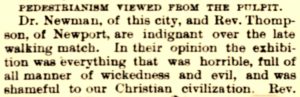

Clergymen Condemn Pedestrianism

Rev Edward Eggleston (1837-1902), Methodist minister and historian, preached, “When you put men on a racecourse for six mortal days and nights together, it has some elements like the old Roman gladiatorial shows. It is liable to result in the destruction of life and bring an abridgment for life.”

Rev Dr. John Phillip Newman (1826-1899), a Methodist Episcopal minister, added, “The pains of a whole life were endured in a week, and the happiness of a life was sacrificed in the same brief time. Is happiness so cheap? Others will be tempted to try and will suffer in turn. We can applaud the fireman and soldier who suffer in the discharge of their duty, but he who inflicts voluntary suffering upon himself defrauds society.”

Well, it was quite an era. If you are racing in an ultra today and the police show up, just act natural. Stay tuned for more Ultrarunning Stranger Things

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources for Episodes 115, 116, 122:

- Steve Brodie (bridge jumper)

- That daredevil Steve Brodie!

- Henry S Tanner (doctor)

- The Daily Record of Times (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Aug 3, 1875

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Jul 29, 1875

- The Courier and Argus (Dundee, Scotland), Dec 14, 1876

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 31, 1879, Feb 15, 1879

- New York Tribune (New York), Apr 15, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 16, 1879

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Apr 17, 1879

- The Sun (New York, New York), Apr 18, 1879, Sep 8-17, 25, 1880

- Buffalo Weekly Courier (New York), Apr 23, 1879, Sep 10, 1889

- Brooklyn Times Union (New York), Apr 25, 29, 1879, Sep 17, 1895

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Mar 4, 1879, Apr 29, May 1, 16-17, 24, 1879

- The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), May 3, 1879

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), May 5, 1879

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), May 15, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Feb 6, Mar 22, 24, 1879, Sep 16, 24, 1880, Feb 24, 1881, May 17, 1886, Jun 17, 1915

- The Norfolk Virginian (Virginia), Jul 8, 1879

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Sep 13, 1879

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), Sep 18, 1879

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Oct 15-22, 1879

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Oct 18, 19, 1879

- The York Daily (Pennsylvania), Sept 3, 1879, Jul 3, 1885

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Apr 29, 1880, Jun 4, 1881

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Mar 5, 1881

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 7, Apr 15, 20, 1879, Sep 16, 1880, Mar 6, Oct 3, 1881, Mar 27, Dec 15, 1883, Mar 8, 1886, Mar 6, 1892, Feb 1, 1901

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Feb 23, Mar 7, 1881

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Jun 6, 1881

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 14, 17, 19, 22, 1879, Feb 18, 1880, Jun 5, Jul 10, 1881, Feb 25, 1883, Nov 9-10, 28, 1886

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Jun 22, 1881

- Nottingham Journal (England), Jan 8, 1881

- Sheffield Daily Telegraph (Yorkshire, England), Nov 16, 1881

- Derby Mercury (Derbyshire, England), Jul 9, 1881, Nov 16, 1881

- The Merthy Express (Wales), Nov 7, 1885

- The Hampshire Advertiser (Southamption, England), Dec 17, 21, 1887

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Sep 9, 13, 1889

- The Shore Press (Asbury Park, New Jersey), Jul 8, 1892

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Jul 19, 1879, Jun 29, 1893

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Apr 28, May 1, 31, 1879, Jul 1-2, 1885, Sep 11, 1894

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), May 17, 1898, Dec 9, 1899, Feb 19, 1904

- The Troy Messenger (Alabama), Mar 14, 1900

- The Buffalo Enquirer (New York), Feb 2, Aug 23, Dec 3, 1900

- The Buffalo Review (New York), Feb 24, 1900

- The Buffalo Times (New York), Nov 22, 1900, Jan 26, 1901

- Miners Journal (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Feb 6, 1901

- Passaic Daily Herald (New Jersey), May 3, 1902

- The Weekly Dispatch (London, England), Jun 12, 1904

- The Macon Telegraph (Georgia), Feb 19, 1904

- The Nottingham Evening Post (England), Jan 16, 1905

- The Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Apr 9, 1906

- Ashbourne News (Derbyshire, England), Aug 23, 1907

- Manchester Courier (England), Sep 11, 1907

- The Tacoma Daily Ledger (Tacoma, Washington), Jun 10, 1908

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), May 13, 1912

- Leicester Evening Mail (England), Jul 4, 1913

- The Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), Jun 16, 1915

- Brooklyn Times Union, Mar 20, 1891

- The Ashbourne News (Derbyshire, England), Feb 2, 1906

- The Staffordshire Sentinel Daily and Weekly (England), Sep 2, 1905

- Midland Daily Telegraph (Coventry, England), Sep 23, 1905

- The Gloucestershire Echo (England), Jan 1, 1907