Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:34 — 34.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

On April 24, 1897, ultrarunning/pedestrian champion Alice Robison was running in second place on the last day of a three-day race held at the Fifth Street Rink in East Liverpool, Ohio, with five runners. She was very intent on catching her long-time friend who was a few laps ahead of her. Needing a rest, she retired to her room provided at the Hotel Grand next door.

On April 24, 1897, ultrarunning/pedestrian champion Alice Robison was running in second place on the last day of a three-day race held at the Fifth Street Rink in East Liverpool, Ohio, with five runners. She was very intent on catching her long-time friend who was a few laps ahead of her. Needing a rest, she retired to her room provided at the Hotel Grand next door.

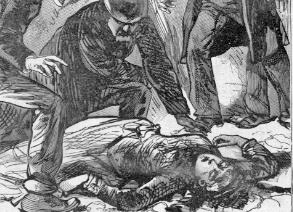

That afternoon, a man came into town on a train from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The mustached man wore a new suit with a price tag still attached, and a white hat with a black band. He went to the hotel and inquired where Alice was staying. He ascended the stairs and went to the third-story room. Shortly after, a gunshot was heard! The porter of the hotel rushed into the room and found the woman on the floor bleeding from a gunshot wound in her head and saw the man leaning over her, holding a revolver. How could this happen, an ultrarunner was murdered during a race!

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Alice Robison’s true name was Agnes Jane Jones (1860-1897). She was from Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, the oldest of eleven children, a daughter of a coal miner. She married very young to James Waters, a coal miner, had three children, and later divorced. In 1882, at the age of 22, she next married again to Zachariah S. Robison (1851-1906).

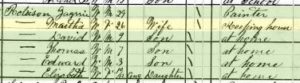

Alice was Zachariah’s second wife. His first wife, Martha Alexandria (1854-1881) from Kentucky, died in 1881 at the youthful age of 27, leaving behind four children who had gone to live with their Robison grandparents. Alice eventually took on the role of mother and stepmother to all these seven children ages 3-12, and then had two more of her own, Robert (1883-) and Georgia (1886-) for nine children in the home on a small farm.

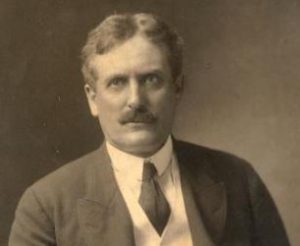

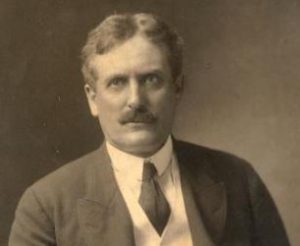

Zachariah Robison

Alice’s new husband, Zachariah Robison, was born in 1851. His Robison ancestors came from Ireland and settled in Beallsville, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles south of Pittsburgh, where his father was a cabinet maker. Of Zachariah it was said, “from the time he was 5-6 years old, he was puny and sickly and frequently had epileptic fits.” When his mother Susan Robison (1831-1906) would discipline him, he would fall to the floor in convulsions and remain unconscious.

Once married to Alice in 1883, the Robison family moved around to various places in the west suburbs of Pittsburgh across the Ohio River. Alice became the boss of the family and was in control of all the family finances, including property in Crofton, Pennsylvania rumored to be worth $10,000. She worked hard as a washerwoman and house cleaner. Both Zachariah and Alice had drinking problems and would get drunk causing difficulties in the family. The oldest son David S. Robison (1871-1931), when age 15 in 1886, did not like the manner of life led by his father and stepmother Alice, so he left home and learned the trade of a tailor.

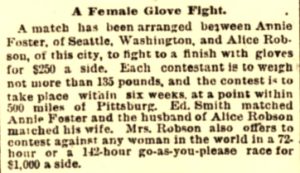

Becoming a Professional Boxer

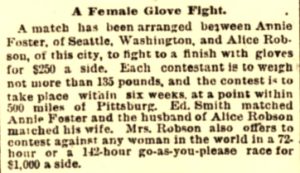

Zachariah also took lessons and the two would box each other. He even sold a small home to help pay for lessons. Alice was very serious, taking four lessons per week and started to make public challenges to fight other women and fought professionally.

Getting Into Pedestrianism

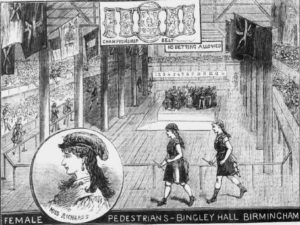

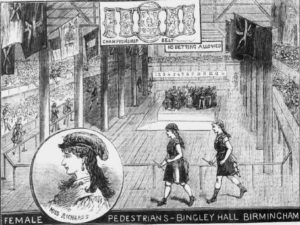

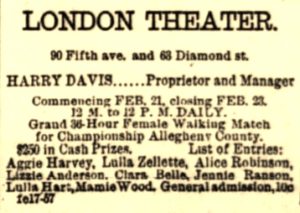

The Robisons became interested in following the sport of pedestrianism and by 1889 Alice jumped in to compete, probably at the encouragement of a friend, Frankie Flemming, who had been competing and was also interested in boxing.

The “Robison” name was always confusing to the sports press. Thus, she was called by several names in competitions, “Alice Robison,” “Alice Robinson,” and “Alice Robson.”

Alice’s First Walking Match

Alice’s Greatest Race

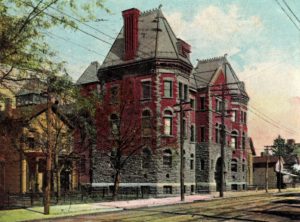

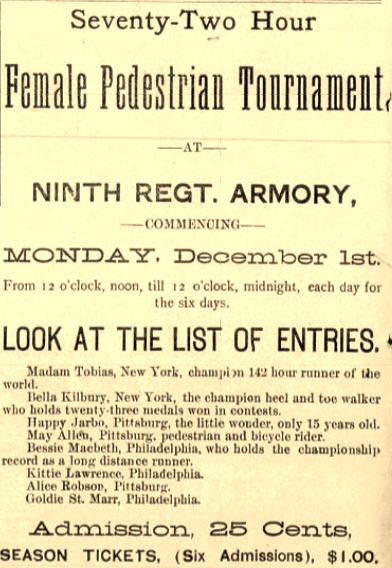

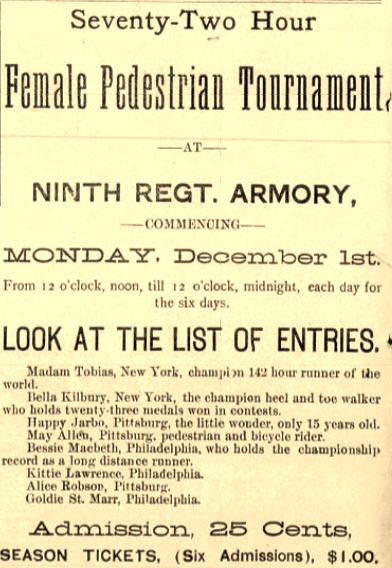

Alice’s greatest race came in December 1890, at a six-day, 12-hours per day race in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in the Nineth Regiment Armory Building. The race began on December 1, 1890, and Alice was crewed by her husband, Zachariah. Among her competition were veteran champions, Sarah Tobias “an old walker, with many medals, and the champion 142-hour woman walker of the world,” and Bella Kilbury the six-day world record holder.

Alice was described as “a tall, black-eyed girl in red and black striped garment with short skirts, is the noisy one of the lot and a good stepper.”

On the second day, Alice withdrew her daughter, Happy Jarbeau, worried that she could not handle the continued strain of the race. The crowd was relatively small, about 500 people. The women had a goal of reaching at least 225 miles, in order to get a share of that gate profits. By day four Alice was leading with 171 miles.

Champion Pedestrian

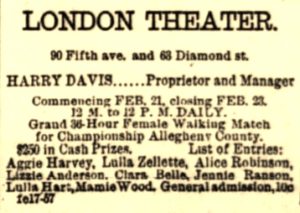

But Alice continued to compete in many races elsewhere in 1892-1893, including Washington D.C., Chicago Illinois, Detroit Michigan, and Baltimore, Maryland, where she went over 264 miles. As a popular champion, she was away from home on long road trips. But then she took the next three years off, as competitions further dwindled.

The Robisons continued to move around and lived for a time in the East Liberty section of Pittsburgh. Family life became a struggle. Zachariah’s heath declined with his drinking and smoking. Alice brought in most of the family income but was also helped by stepson Thomas Robison (1873-) who took up painting jobs with his father. Zachariah’s mood became melancholy. Thomas said, “I noticed it in his walk. He stooped over, and never looked around.” He would complain of sleeplessness, act erratic at times, and fall down on the floor experiencing a fit like he had as a child. Alice said that it seemed like he was losing his mind.

Chuck Stewart Arrives

In 1895, a young man, Charles “Chuck” Stewart (1872-1924), age 23, came into the lives of the Robisons. He was known by police in the area of being a “troublemaker.” He was convicted of burglary in 1891 and was in and out of the workhouse/prison eight times for being convicted of assault, battery, and disorderly conduct. He was generally lazy and did not hold down jobs. When he did work, he was a slate roofer and was said to be a big, good-looking man.

Stewart started to visit the Robisons regularly and drink with them. He claimed to have no place to live, being thrown out of his house by his father because of his drinking. Alice took pity on him and wanted him to move in with the family, but Zachariah would not consent. Since Alice was the family boss, she let him move in anyway. He was pretty much a freeloader, rarely taking on work, would come in drunk, and sleep in late.

Every few months, the three of them would go on a big drinking binge when Alice would bring home as much as a gallon of liquor. As Zachariah became drunk, Alice and Stewart would even pour booze down his throat and then go out together, sometimes all night. Son, Thomas became suspicious and warned his father that something was going on between Alice and Stewart. But Zachariah couldn’t believe it, he loved her so much. When he confronted Alice, she scoffed at the idea, claiming that nothing could ever come between them, and that Stewart had a transmittable disease anyway.

Three-Day Race in East Liverpool, Ohio

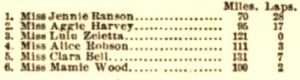

Alice decided that she wanted to make a pedestrian comeback and run a race in East Liverpool, Ohio, about 60 miles away. Her longtime friend, Agnes “Maggie” (McShane) Weigand (1870-), who had entered the race, invited her to go. Maggie’s stage name was Aggie Harvey, and she was a very experienced pedestrian who held the world record for a six-day, 8-hours per day race distance of 200 miles. Alice asked Zachariah if she could go, and he consented. She left their East End, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania home on April 19, 1897.

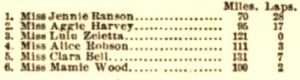

The race, held at the Fifth Street Rink, was rather disorganized. There was first a men’s race the first three days and then then a women’s race was started but only ran for 3 ½ hours on the first day. By the next day, Robison was in second place, chasing her friend Agnes, who was only five laps ahead. She was confident that she would overtake her. It was reported, “The scenes at the race during the week were disgraceful in the extreme.”

A Love Letter Found

Zachariah showed the letter to his son Thomas, who confirmed his suspicions that Alice had been unfaithful. Robison became distraught, could not concentrate on work, and left to go confront Alice in Ohio. He first stopped to see her close pedestrian friend, Frankie Fleming, and showed her the letter. Frankie had been increasing disgusted with Alice’s lifestyle and mentioned that once on the road for a race in Manchester, New Hampshire, she had discovered Alice drunk in bed with multiple men. This further disturbed Zachariah and he left.

Confrontation

Zachariah arrived at East Liverpool by train and immediately went to the Hotel Grand, next door to the rink where the race was being held. He first got a shave from the barber and then took a half hour to figure out which room Alice was in. He finally knocked on the right door. Her friends, George and Agnes Weigand were there, along with the race manager Edward G. Wilson. They were preparing for the final six-hours spurt of the race and Alice was in the process of packing up her things to leave for home the next day. “He went right in her room, and Alice spoke to him and told him she was glad to see him.” She had been expecting him to come and help for the last day of the race. She asked how the folks were doing at home. His calm reply was, “Whom do you mean, your lover?”

Her friends left the room so they could be alone. Zachariah then confronted her about the letter. About ten minutes later, he went to the room of her friend, Agnes. He asked her if Alice had been receiving letters from Stewart. Agnes later said, “He said she had been unfaithful and called her the vilest of names. While he was talking, Alice came to the door of the room and asked him to come to her room, as she wanted to see him.”

They talked, came out, and Agnes warned Alice that she should stay away from him until he cooled down, because she saw that he carried a revolver in his right hip pocket. Zachariah and George Weigand went out of the hotel to view the track in the rink and get some drinks at Joseph Geon’s Saloon. Zachariah stated that he planned to help Alice with her race during that night. While he was away, Alice, probably fearing that her husband would see more of her mail, went to tell a porter that if any mail came for her, that it should be delivered to Agnes.

Fatal Shot Fired

George Weigand had heard the shot, tried to get in the door but it was locked. He went down and got George Perry and the hotel porter, Robert Donaldson from the hotel bar to go with him to investigate. He said, “I went into the room. Mrs. Robison was lying on the floor and he was kneeling beside her sponging her eyes. Robison said it was only a flesh wound and I told him he had better give the gun to Perry.” Alice was moaning with blood streaming from a hole in the corner of her right eye.

A doctor was telephoned for, but it was clear that there was no hope. Zachariah showed no emotion. He went back over to where Alice lay, then leaned down and kissed her. He kept saying, “It is only a flesh wound. She’ll be all right in a little bit.” When the doctor came, he mentioned that he did not want to pay for the bill. He was heard mumbling, “This is what women get for trifling with their husbands.”

Robison Arrested

Strangely, the race continued. “Often the opinion was expressed that the place should be closed by the authorities. There was a crowd at the race Saturday night, and when a well-known resident asked a young man connected with the race why the place was not shut up in view of the tragedy, he brutally replied, ‘Oh a little thing like that wouldn’t affect us.’” Soon the match was stopped by the police, and they detained all of the participants as witnesses. The race manager, Wilson, quickly skipped out of town without paying the bills.

The next day, Major Gilbert visited Robison and informed him that his wife was dead. A hearing was held, and Robison plead not guilty to first degree murder.

Robison’s Trial

Robison’s ten-day trial started about two months later, on Jun 15, 1897, in Lisbon, Ohio, and certainly was the trial of the year for that area. Multiple pages of details were carried daily in the local newspaper. Dozens of witnesses were called. The defense strategy initially was to try to prove that Robison was insane or that he was defending himself from an attack by Alice while they were alone in the hotel room.

On the second day of the trial, the love letter from Alice to Chuck Stewart was read, and it was the first time Robison showed any emotion. “On hearing the terms of endearment in the letter addressed to Stewart, Robison’s form was shaken with sobs, and for five minutes he wept piteously.”

Chuck Stewart’s Strange Testimony

The Prosecution’s Case

Later in jail, Robison complained about pain in his heart from the death of his wife. He said, “I don’t care, they can send me in the chair and electrocute me if they want to.” He seemed to be detached from the reality that he caused her death.

Closing Arguments

The Verdict

Later back in his jail cell, Robison said, putting down a Bible, “The past four months are like a dream. My mind at times has seemed blank. I have been dazed and I think it took something like the shock of the verdict to make me normal. I am innocent of killing my wife. But it was through me she died, whether intentional or not, and I feel that I loved her well enough to suffer death now for the harm I have done her.”

The news went out across the country, “the story of the tragedy is the old one of woman’s frailty and man’s maddening jealousy.”

The Death Sentence

The Appeal

A couple of months later, the judge claimed that a technical error was found in the proceedings of the case, and he referred the matter to the Circuit Court. A book of 891 pages, five inches thick, was sent to the court. In the meantime, Robison was the model prisoner in the Columbus Penitentiary. He mostly kept to himself, reading, and he received a few letters from family and friends. His youngest children went to live with their Robison grandparents.

The Plea Deal

Prison Life

Robison Released from Prison

Robison went to live quietly with his son Edward who worked for the railroad in Donora, Pennsylvania, 25 miles south of Pittsburgh.

Zachariah S. Robison died Sept 9, 1906, in Mercy Hospital at Pittsburgh, at the age of 54 from alcoholism and lead poisoning. He was buried in Beallsville Cemetery, where his first wife and other family members were buried. His mother died a week earlier at the age of 75, and his father died the following year.

Alice Robison has been forgotten for more than a century. She had hundreds of descendants living today who never knew the tragic story of their famous ultrarunning great-great-great grandmother Alice Robison.

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- The Evening Mail (Stockton, California), Dec 7, 1887

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Nov 27, Dec 28, 1887

- Pittsburgh Dispatch (Pennsylvania), Feb 17, 21-23, 1889, Apr 10, Jun 9, 1891

- The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), Oct 2, 1889

- Miners Journal (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Dec 2, 1890

- Wyoming Democrat (Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania), Dec 5, 1890

- The Times Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Dec 2-3, 5, 1890

- Sunday News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Dec 7, 1890

- The Anaconda Standard (Montana), Sep 6, 1891

- Minneapolis Daily Times (Minnesota), Apr 5, 1892

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Aug 13, 1891, Apr 25, 1897

- The Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio), Apr 17, 26-27, Jun 15-28, Jul 7, 19, 21, 24, Aug 17, Sep 1, 29, Oct 5, 20, 1897, Sep 13, 1900, Nov 13, 1901, Jul 25, 1902, Mar 6, Dec 2, 1903, Jul 14-15, 1904

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), May 5, 1887, Apr 25, Jun 15, 1897, Aug 30, 1906