Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:17 — 30.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

By 1906, when the pedestrian era was over, most of the elite pedestrians turned to legitimate professions to support their families. Daniel O’Leary was traveling for a big publishing house. John “Lepper” Hughes was in the real estate business, Jimmy Albert was a Texas cattleman, Robert Vint was an oil agent in Russia. Samuel Day was a house painter in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

By 1906, when the pedestrian era was over, most of the elite pedestrians turned to legitimate professions to support their families. Daniel O’Leary was traveling for a big publishing house. John “Lepper” Hughes was in the real estate business, Jimmy Albert was a Texas cattleman, Robert Vint was an oil agent in Russia. Samuel Day was a house painter in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

But many others had a darker side, driven by motivations of greed and were not necessarily the most outstanding citizens. It should not be too surprising that many were involved in wild free-spending lifestyles, scandals, illegal activities, and run-ins with the law. This episode will concentrate on the strange darker side of the sport during the late 1800s. Future episodes will focus on corruption during the races and some bizarre love triangles among the running community.

| Run Davy Crockett’s Pony Express Trail 50 or 100-miler to be held on October 14-15, 2022, on the historic wild west Pony Express Trail in Utah. Run among the wild horses. Crew required. Your family and friends drive along with you. http://ponyexpress100.org/ |

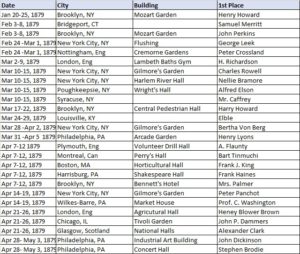

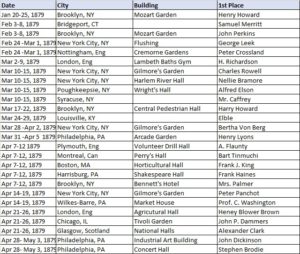

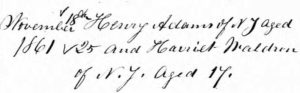

Publicity Fraud and Redemption

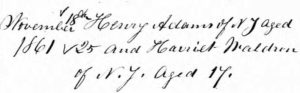

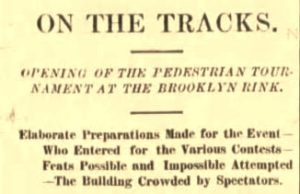

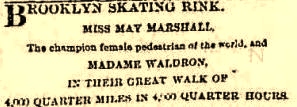

In January 1879, Adams (Madame Waldron) walked 150 miles in 50 hours at the Adelphi Theatre in New York City. Next, on March 3, 1879, she competed in an “International Pedestrian and Billiard Tournament” that was held at the Brooklyn Roller Skating Rink, near Dr. Justin D. Fulton’s Temple. Pedestrians, male and female from nine countries attempted various walks for huge money on seven sawdust tracks, each 20 laps to a mile, set up in the building. It was an amazing spectacle. “Its entire appearance had been changed from a mammoth, bleak and dreary barn to a bright and cheery place of amusement. Between the tracks were placed rows of evergreens, shrubs and flowing plants which gave the floor much of the appearance of a garden. Three full-sized billiard tables were placed in a space in the center of the rink. From the roof were pendant hundreds of bright flags. At the rear of the hall was a large music gallery.”

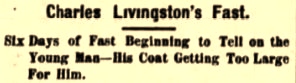

Fasting for 42 Days

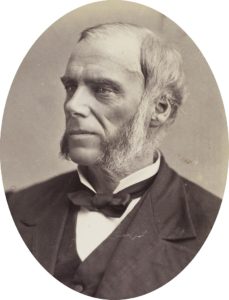

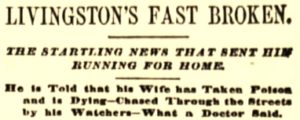

Livingston’s crazy fast began on September 7, 1880, at a beer saloon at 5 Willoughby St., Brooklyn, New York. He claimed that in the past he had fasted 23 days and he wanted to go after a 42-day record held by a Dr. Henry S. Tanner (1831-1918), completed a month earlier. Livingston said, “I don’t care for food, it has no temptation for me, and I can go without eating or sleeping without any inconvenience.”

He was allowed to drink water. To verify the stunt, one “watcher” was always on duty. Livingston spent much of his days relaxing and chatting in an easy chair donated by a furniture store. He loved the attention that he was getting in the New York City newspapers, and his stunt started to be reported nationwide. Spectators coming to see him started to be charged admission after the second day. His manager, T. J. Murphy said, “If he wants to starve, I will give him a good chance.”

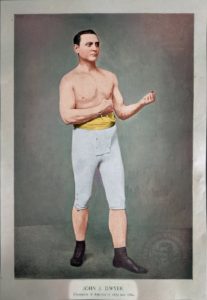

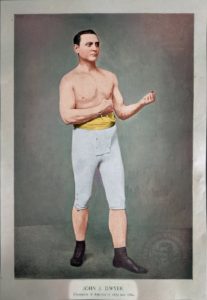

Many callers came each day to visit him including John Dwyer (1847-1882), the ex-prize fighter and Congressman Daniel O’Reilly (1838-1911). “Livingston sat near the front window of the hall, and his wife sat most of the day by his side. He is her second husband, and they are an affectionate couple. She is many years his senior.”

After just four days, Livingston, age 26, was getting thin and complaining that his clothes were too large on him. Oddly, his face still looked full, and he had not yet weighed himself. Dr. Tanner was very skeptical of the stunt, stating that “unless physicians watch him, the genuineness of his fast will be doubted.”

On day seven, Hattie visited, still insisting that Livingston stop, and told him falsely that his father died from a heart attack and that he must leave immediately to attend the funeral. Livingston didn’t buy the story and didn’t budge.

On the nineth day, Hattie sent word to her husband at the barroom that she was sick in bed with heart disease and wanted him to come see her. He and the two watchers went to his home at 358 Atlantic Avenue, but she looked as healthy as ever. She insisted that he stop his fast or she would be the one who would die. Livingston refused to stop and returned to the bar.

Hattie was moaning, a cup containing bedbug poison was on a table near her bedside. “He came out to his watchers and announced that after eight days and ten hours, he would stop his fast, as his wife was bound to get him home.” The ambulance was going to take her to the hospital, but Livingston said that there was nothing wrong with her, that the poisoning was a ruse. The press wrote, “Starvation is the last resource of the lazy man. A lazy person would rather starve to death than work.” It was believed that Livingston belonged to that class of people. Livingston immediately drank a glass of beer and ate three crackers. The next morning, he started to look for a job.

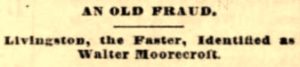

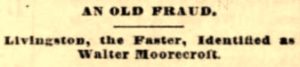

Fasting Fraud Revealed

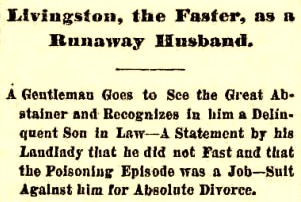

Livingston’s landlady, Mrs. Fisher revealed that the entire fasting event was a fraud. Hattie had secretly supplied him with food and stimulants and was in on the hoax. “Mrs. Fisher also let it be understood that the poisoning dodge was a job put up between Livingston and his wife as a dramatic close to the fasting imposture.”

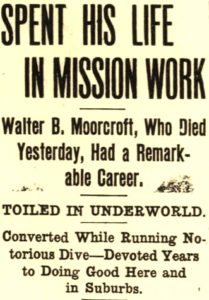

Lives Turned Around

Finally in 1894, something happened. Moorcroft underwent a spiritual conversion one evening and immediately telegraphed his bar with instructions to close the business. His employees thought the police were after him. “But Moorcroft disabused everyone’s mind by hurrying down to his saloon, taking out all the bottles of whiskey and emptying them into the sewer and then doing the same with every drop of alcoholic beverage he had in the place. Not a bottle of flask or keg was left unemptied by Moorcroft.” He sold his business and donated the money toward fallen girls of New York City.

Moorcroft later explained, “I had a big business and made money, loads of it. I never was bothered by any pangs of self-reproach or remorse. I was a laughing sinner. One day, I was moved to enter the John Street Methodist church that I happened to be passing. A half hour later I was a saved man, born again.”

He then joined the Methodists and started work as a fulltime missionary. He put his heart into the rescue mission and in 1895 was described as “a gentleman possessing an aggressive and intense personality, full of humane kindness, with the courage of his convictions, with one idea to administer succor to the outcast and abandoned.” He and his wife lived at the mission.

Later they moved to New Jersey in 1901 and opened missions in Ridgewood, Lodi and Paterson and were involved with the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. “He took in free of charge hundreds of men and women rather than have them arrested for either drunkenness or disorderly conduct and sent to jail.”

| Please help the ultrarunning history effort continue by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Signup at https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

Runner becomes a Horse Thief

Prater was an engineer and gained national fame for constructing a model of the Brooklyn Bridge that weighed 750 pounds and had 350 figures (people, carriages, boats, etc.) But he was constantly in trouble with the law for beating people up and committing other crimes. He paid many fines and spent time in prison.

In 1898, a horse, buggy, harness, and bridle were stolen from different owners in Georgia. Through good detective work, Sherrif Durham believed that Prater was the thief and tracked him down in Albertville, Alabama with the horse and buggy. Prater had become very popular in the city with young people, attended picnics, and led a choir at Sunday School. But as the old adage says, “Things are seldom what they seem.”

A year and a half later, Prater was finally apprehended. “A pair of handcuffs fastened to one end of a chain were snuggly clasped around Prater’s wrists and the other end of the chain tightly held by the big sheriff, who said he was carefully guarding against the escape of his prisoner in case the old walking feeling should come over him again.” At his trial, the jury found him guilty, but gave a recommendation of mercy. Before the judge rendered a sentence, Prater finally confessed that he was guilty. He was sentenced to two years in prison.

In 1904, out of prison, Prater was run over and killed by a train in Macon Georgia. He met his death at a crossing that citizens called “a death trap.” The train operated over the crossing with no regard for city laws. Prater left behind a wife and four children. His widow, Belle C. Prater, filed a $25,000 suit against Southern Railway.

A Public Nuisance

In 1875 as Weston and O’Leary were gaining fame, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a man agreed to walk from the Opera House to Thirtieth Street, a little more than two miles, in 22 minutes for $25. “He started shortly after 7:00, dressed in an easy walking costume and his rapid strides soon attracted an immense crowd, which kept increasing at every step he took. His followers were shouting ‘there goes Weston,’ ‘look out for O’Leary,’ etc. A detective considered the rabble somewhat disorderly and requested the walkist to desist, but as he signified his intention of walking on, the officer walked him off to the Central station.” His friends paid for his bail.

In 1885, William Buckler, age 36, “the great Newport pedestrian” who had just completed a walk of 306 miles between Aberdare and Pontypridd, Wales, in six days was arrested and appeared in court. Buckler had been seen walking in Aberdare, in a light pedestrian costume followed by a large crowd of men, women, and children. The complaint was, “If anybody wished to drive a carriage along the street at that time, they would have had considerable difficulty in doing so.” Apparently, that had happened several times before.

![]()

![]()

For the next two decades, Buckler continued to attempt ultra-distances walking stunts in many towns, including his version of the backyard ultra in 1907, walking 2,300 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours, 2 miles and 530 yards each hour for 41 days, in Halifax, England.

Apparently, such arrests were common in Great Britain. In 1876 four local pedestrians were convicted for foot racing on a public Highway in Aberdeen, Scotland. “A crowd was collected, and the traffic obstructed. The defense claimed that the four had been allowed to race by two policemen, but then he waited until the first race was over and made the arrests.”

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources for Episodes 115, 116:

- Steve Brodie (bridge jumper)

- That daredevil Steve Brodie!

- Henry S Tanner (doctor)

- The Daily Record of Times (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Aug 3, 1875

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Jul 29, 1875

- The Courier and Argus (Dundee, Scotland), Dec 14, 1876

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 31, 1879, Feb 15, 1879

- New York Tribune (New York), Apr 15, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 16, 1879

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Apr 17, 1879

- The Sun (New York, New York), Apr 18, 1879, Sep 8-17, 25, 1880

- Buffalo Weekly Courier (New York), Apr 23, 1879, Sep 10, 1889

- Brooklyn Times Union (New York), Apr 25, 29, 1879, Sep 17, 1895

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Mar 4, 1879, Apr 29, May 1, 16-17, 24, 1879

- The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), May 3, 1879

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), May 5, 1879

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), May 15, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Feb 6, Mar 22, 24, 1879, Sep 16, 24, 1880, Feb 24, 1881, May 17, 1886, Jun 17, 1915

- The Norfolk Virginian (Virginia), Jul 8, 1879

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Sep 13, 1879

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), Sep 18, 1879

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Oct 15-22, 1879

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Oct 18, 19, 1879

- The York Daily (Pennsylvania), Sept 3, 1879, Jul 3, 1885

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Apr 29, 1880, Jun 4, 1881

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Mar 5, 1881

- The New York Times (New York), Mar 7, Apr 15, 20, 1879, Sep 16, 1880, Mar 6, Oct 3, 1881, Mar 27, Dec 15, 1883, Mar 8, 1886, Mar 6, 1892, Feb 1, 1901

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Feb 23, Mar 7, 1881

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Jun 6, 1881

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 14, 17, 19, 22, 1879, Feb 18, 1880, Jun 5, Jul 10, 1881, Feb 25, 1883, Nov 9-10, 28, 1886

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Jun 22, 1881

- Nottingham Journal (England), Jan 8, 1881

- Sheffield Daily Telegraph (Yorkshire, England), Nov 16, 1881

- Derby Mercury (Derbyshire, England), Jul 9, 1881, Nov 16, 1881

- The Merthy Express (Wales), Nov 7, 1885

- The Hampshire Advertiser (Southamption, England), Dec 17, 21, 1887

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Sep 9, 13, 1889

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Jul 19, 1879, Jun 29, 1893

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Apr 28, May 1, 31, 1879, Jul 1-2, 1885, Sep 11, 1894

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), May 17, 1898, Dec 9, 1899, Feb 19, 1904

- The Troy Messenger (Alabama), Mar 14, 1900

- The Buffalo Enquirer (New York), Feb 2, Aug 23, Dec 3, 1900

- The Buffalo Review (New York), Feb 24, 1900

- The Buffalo Times (New York), Nov 22, 1900, Jan 26, 1901

- Miners Journal (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Feb 6, 1901

- Passaic Daily Herald (New Jersey), May 3, 1902

- The Weekly Dispatch (London, England), Jun 12, 1904

- The Macon Telegraph (Georgia), Feb 19, 1904

- The Nottingham Evening Post (England), Jan 16, 1905

- The Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Apr 9, 1906

- Ashbourne News (Derbyshire, England), Aug 23, 1907

- Manchester Courier (England), Sep 11, 1907

- The Tacoma Daily Ledger (Tacoma, Washington), Jun 10, 1908

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), May 13, 1912

- Leicester Evening Mail (England), Jul 4, 1913

- The Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), Jun 16, 1915