Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:30 — 39.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

On a summer morning in 1883 in midtown Manhattan, New York City, a young boy ran down 34th Street, getting the attention of a policeman. He cried out, “A man has killed some folks.” Officer John Hughes ran with the boy to a new saloon that recently opened. There he saw a man, pale, and trembling. He found out that the man was George Noremac, one of the most famous ultrarunners/pedestrians in the country.

On a summer morning in 1883 in midtown Manhattan, New York City, a young boy ran down 34th Street, getting the attention of a policeman. He cried out, “A man has killed some folks.” Officer John Hughes ran with the boy to a new saloon that recently opened. There he saw a man, pale, and trembling. He found out that the man was George Noremac, one of the most famous ultrarunners/pedestrians in the country.

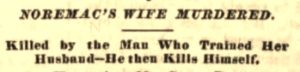

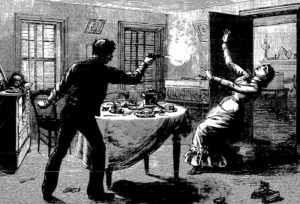

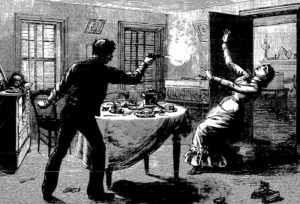

Noremac led the officer up two flights of stairs to the apartment where he lived. On the dining room floor lay two dead bodies, Noremac’s young wife, Elizabeth, and his longtime friend and trainer, George Beattie. A revolver lay on the floor near Beattie’s left hand. The murder and suicide occurred while Noremac was downstairs, but his two young children, still crying, had sadly witnessed it all. How could this have happened?

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

As a young adult George became interested in running in 1872 at the age of 20. His first achievement was winning a one-mile race in 5:13 at Powder Hall Grounds, Edinburgh, Scotland. He quickly became recognized as one of the best sprinters in Scotland and would compete in various one-mile races during town fairs, always placing high. He improved his one-mile personal best to 4:21 and won three-mile races too.

Entering Pedestrianism Sport

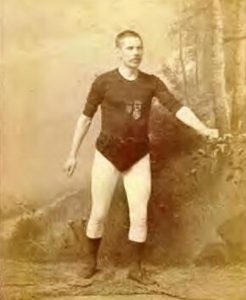

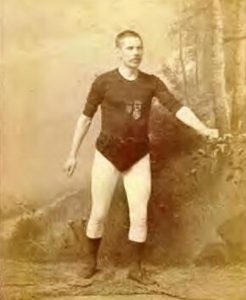

In 1879, long-distance pedestrianism started to get intense attention in Scotland as Edward Payson Weston barnstormed Great Britain, putting on walking exhibitions and competing in races. With so many others, George entered the sport that year. He was a small man, ideal for long-distance running, standing only 5’3”” and weighing about 122 pounds.

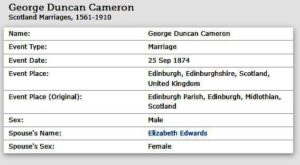

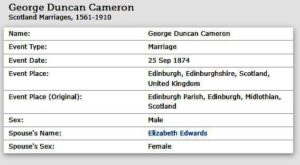

He decided to take on the stage name of “Noremac” which is Cameron spelt backwards. He did not originate the idea of using his transposed name as an alias. Other Camerons before him had also used the Noremac alias both in Scotland and America.

Noremac’s earliest known ultra-distance race came in July 1879. He ran in a 26-hour, outdoor six-day running tournament, at the Aberdeen Recreation Grounds in Inches, Scotland. Contestants ran four hours a day and six hours on the last day. It was put on by the 100-mile world record holder, George Hazael of London. “By the finish, an immense concourse of people had congregated within the enclosure, who seemed to take on eager interest in the competition, cheering one or other of the competitors whenever a spurt was made.” Noremac reached an impressive 156 miles.

Noremac continued to win nearly every race. In January 1880, a two-day (12-hours per day) race was held at Perth, Scotland in Drill Hall. There were 23 starters. The track was very tiny, 31 laps to a mile. Noremac led after the first 12-hours with a remarkable 69 miles. He won by ten miles with a total of 138 miles after the two days.

Noremac’s Trainer

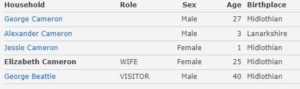

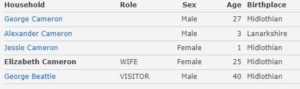

As Noremac became serious about being a professional pedestrian, he hired George Beattie, age 40, to be his trainer/handler. He him in London and hired him. George Beattie (1839-1883) was from Scotland, had been a private in the British Army for 22 years, and served 12 years in India where he took part in the Afghanistan war in 1878-79. He belonged to the Fifth Rifle Brigade where he became a skilled rifleman and participated in competitions. He had recently retired as a sergeant from the service and was living on a soldier’s pension, received quarterly. With no living relatives, he went to live with Noremac’s family.

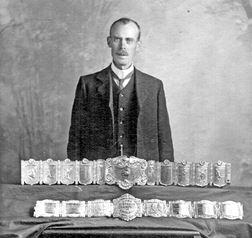

Prolific Successful Ultrarunner

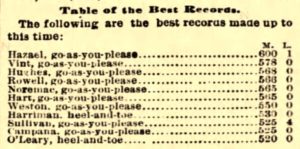

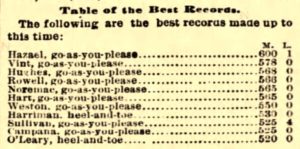

![]()

![]()

With his great success, Noremac started to compete on the bigger stages outside of Scotland and ran in his first six-day race without a daily limit in hours at the Victoria Hall in Newport, Wales, reaching 459 miles, winning 70 pounds valued at $10,500 today, probably more than he could earn in a year doing his printing job.

His friend Beattie traveled with him, performing attendant duties during his races. Noremac received special recognition by athletic clubs after he broke a British record running 66 miles in 10 hours, outdoors, at Arbroath, Scotland.

Noremac wanted to next compete against Blower Brown of Fulham for the six-day long distance championship of England Astley Belt, but terms with Brown could not be reached. With this frustration he set his sights on competing in America where there were more opportunities to race for big money.

To America

On May 27, 1881, Noremac and Beattie sailed out of Glasgow, Scotland for America. He left his wife, Elizabeth, behind in Edinburgh where she had a candy shop. He had his eyes on competing in a Rose 72-hour contest to be held on Coney Island. He did not know at the time, but with what he found in America, he had left his homeland behind forever. They arrived in New York City on June 10, 1881, and on July 3, 1881, he won the Coney Island race.

Using his winnings, Noremac opened saloon called “Walker’s Rest” at Prince and Mulberry Streets across from The Basilica of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in today’s Nolita district in Manhattan. He moved into an apartment above the saloon with Beattie, who worked in the saloon as a bartender. Now settled, he sent Beattie back to Scotland to bring pregnant Elizabeth and his two little children to join him in America. They arrived on October 12, 1881, on the steamship Circassia. A daughter, Jane, was born in New York City that year.

Ennis Six-day Race

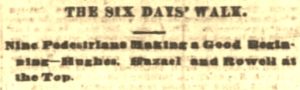

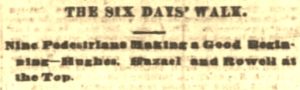

The start was witnessed by 3,000 people. Noremac started slow but each day climbed the leaderboard. Throughout his career he became known as a slow starter who then ran negative splits later in the week. Competitors learned that no early lead over him was safe. “Noremac aroused the boys in the dull hours long before daylight by performing lively Scotch airs on an accordion while running the race. The other racers fell in behind him, keeping step to the tunes when they were not too fast.”

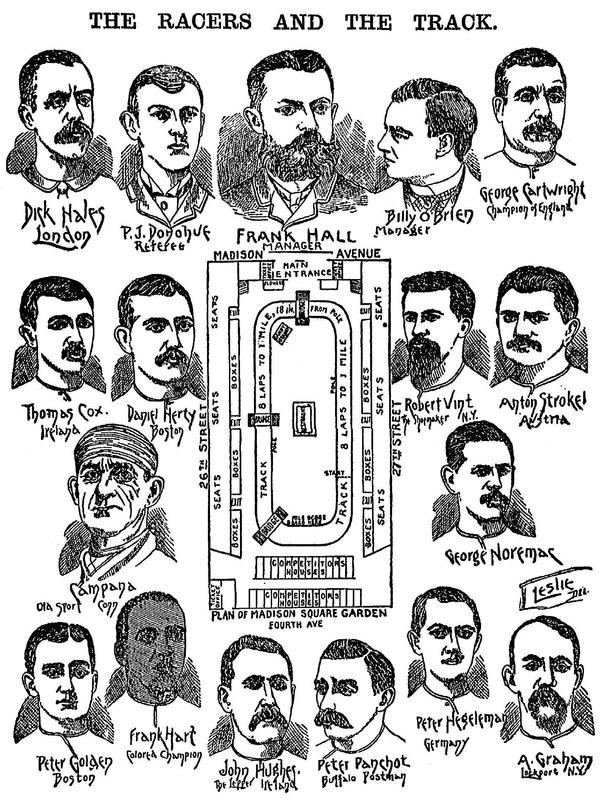

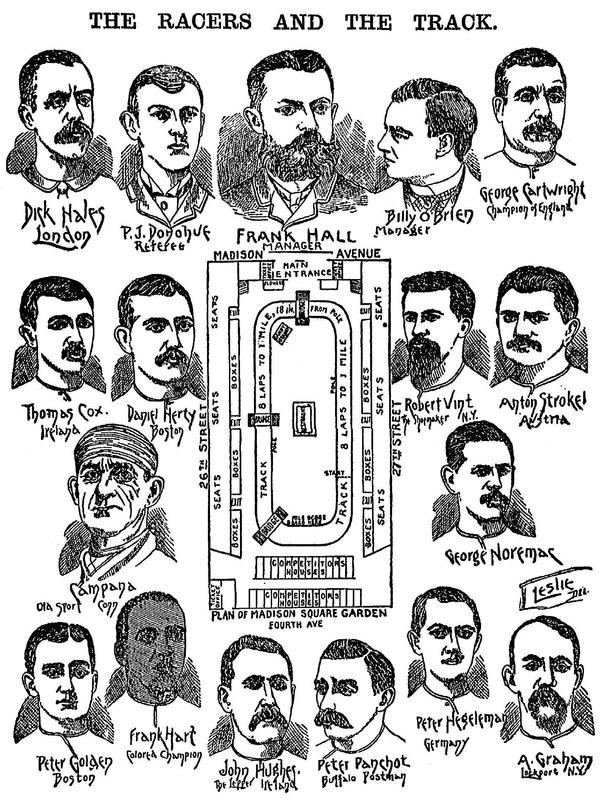

Diamond Whip Six-day Race in Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden was heated by steam and during the night illuminated by 30 electric lights. Certain windows were boarded up to keep the gatecrashers out. “The book-makers were in full force with their tin boxes and sat at little tables near the stand fitted up for newspaper reporters, timekeepers, and scores.” Patrick Gilmore’s 50-piece band was hired to play popular songs. The start was witnessed by about 8,000 people. “The great gathering was in an uproar of excitement when at 12 o’clock by the judges’ timepiece, Referee Busby gave the word ‘Go.’ The champions bounded away like deer.”

The race initially was highly competitive without drama. “Although the crowd was large, there was less enthusiasm manifested than has been witnessed in previous contest. Except when the band of musicians gave vent to their feelings, the scene was almost funereal. The spectators stared at each other oftener than they did at the champions.” The massive bar did good business but ran out of beer and liquors during the first night.

Noremac’s Family life had its sadness. On July 20, 1882, their one-year-old daughter, Jane died at their home at 47 Prince, Manhattan, New York City and was buried in Calvary Cemetery. Elizabeth was pregnant at the time and a few months later gave birth to another daughter, Georgina.

Championship of the World

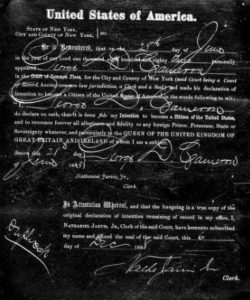

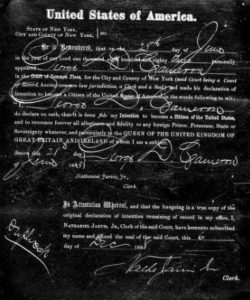

Sadness returned to his family when their one-year-old daughter, Georgina died. This was Noremac and Elizabeth’s fourth child that died in infancy. He refrained from racing for several months and likely concentrated on his saloon business. On June 21, 1883, Noremac became a U.S. citizen. Life looked good in America for Noremac.

Family Strife

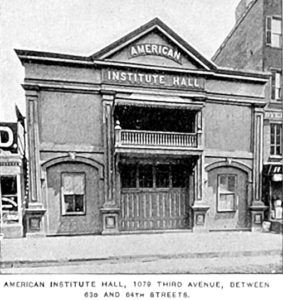

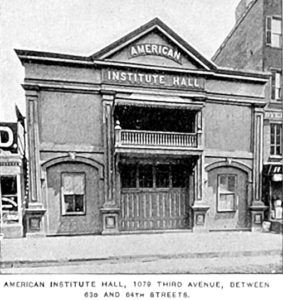

In August 1883, Noremac sold his saloon and opened a new one located on 466 8th Avenue between 33rd and 34th street, called “Midlothian Arms,” in Midtown Manhattan. A saloon was on the first floor and the basement contained a billiard room and a bowling alley. On the third floor, was a nice five-room family apartment with a front parlor, two bedrooms, a dining room and a kitchen. He spent all his savings on the new place.

The living quarters was crowded. Noremac’s trainer, Beattie living with them, slept on a sofa in the parlor. Peter Campbell, Noremac’s brother-in-law and James Barclay, as Scotsman, lived in one of the bedrooms. Noremac, his wife and children slept on a large folding bed in the dining room. Another boarder had used the other bedroom, but he had just died from a stroke.

When Noremac and Elizabeth returned one evening from a picnic of the Midlothian Society, he discovered that Beattie had been drunk and used abusive language toward the workmen who were putting on the finishing touches for the saloon. “A quarrel between the two men led to blows and Noremac knocked Beattie down and gave him two black eyes. Beattie decided to go to Canada, where he could collect his pension money, but he continued to remain an unwelcome inhabitant of the house.”

Beattie thought that Noremac had become ungrateful of all his work for him over the years. Elizabeth had become fed up with Beattie, declaring that he was a nuisance in the house. Beattie, probably in a fit of revenge, told Noremac that Elizabeth had been going out secretly at night, implying that she was having an affair with someone. He was obviously causing some serious domestic stress in the family.

It all came to a head on morning of August 23, 1883. “Noremac threw out some hints of what Beattie had said about her while she was making ready to get breakfast. She was angry and when her husband was going downstairs, she said to him ‘Beattie has been telling you some lies about me.’” Her look was so calm that Noremac made some light reply and went down to the saloon without giving it a further thought. It is believed that after he left, she confronted Beattie about his lies, and they had a terrible argument.

Murder – Suicide

A little of 10 a.m., a boy ran down West 34th Street and got the attention of a patrolman, John Hughes, telling him that he needed to go to 466 8th Avenue. He asked the boy why. The reply was, “A man has killed some folks.” That got Hughes attention and he ran to the four-story brick building where Noremac had his new saloon and living quarters on the third floor.

“Elizabeth Cameron lay near the door of a small kitchen She had been killed by a bullet which passed through her head. Beattie’s body was in the opposite corner, near a window. He was shot in the left side of the head, near the ear. A large 44-calibre ‘British bulldog’ revolver lay on the floor near his left hand.” On the dinner table were three place settings for breakfast with bread, fried onions, and some newly cooked liver.

“Elizabeth Cameron lay near the door of a small kitchen She had been killed by a bullet which passed through her head. Beattie’s body was in the opposite corner, near a window. He was shot in the left side of the head, near the ear. A large 44-calibre ‘British bulldog’ revolver lay on the floor near his left hand.” On the dinner table were three place settings for breakfast with bread, fried onions, and some newly cooked liver.

“Noremac looked at his wife’s body for a moment and then sat down on a chair and buried his face in his hands.” The policeman took him out of the room and downstairs and brought to him his six-year-old son, Alexander, who sadly had witnessed the killings.

How it Happened

Noremac went upstairs to find his children screaming and his wife dying. She gave a last gasp and died without a word. Little Alexander was crying, “Mamma is killed! Mamma is dead.” Noremac picked up the two children, moved them to another, and then went back downstairs, staggered, and fell into a chair, pale, hardly able to speak and asked someone to get a policeman. A boy was sent.

Once the police were through with the investigation after a couple hours, Noremac said to a friend, “Get his body out of the house. Don’t let him stay a moment longer than you can help.”

Noremac stepped aside from racing for eight months to get his life back together and to start training again. He soon married again to “a little Scotch woman.”

Running Again

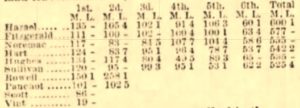

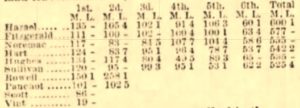

In April 1884, Noremac ran again for six days in Madison Square Garden, where Patrick Fitzgerald broke the world record, raising it to 610 miles. Noremac finished 4th place, with 545 miles, winning $1,400, his fifth time going over 500 miles in six days. He was on his way again to compete regularly.

In July 1884, there were strange happenings at a six-day race in Chicago. On the first day, hot-head John Hughes claimed that scorers deducted 10 miles from his score. Noremac stepped off the track and struck Hughes. Then a runner riot started. Burns, Hart, and a backer kept up the disturbance and were arrested. Burns even struck an officer. Noremac quit the race. Daniel O’Leary, who put on the race, denounced Hughes’ behavior. “He said Hughes was a chronic kicker and had been barred from walking matches all over the country. He started the fight.”

5,100 Mile Walk

For entertainment, a piano and violin played to spur him on. He ate six meals a day and fell to only 102 pounds at one point. He said his run was “spiritless, and the excitement was wanting, hence the task was monotonous and dreary” He succeeded on February 26, 1884. This was his most famous accomplishment.

However, some sporting authorities said they would not sanction the record for administrative reasons. “He was scored and clocked by competent and reliable people, but he failed to request the assistance of some authority so that the great feat, when accomplished could not be gainsaid as a record. The fact that he failed to have the timing and scoring authenticated debars the performance from taking precedence over Weston’s feat.” He vowed to do the attempt again with proper scoring, but never did.

Normac was asked why many pedestrians smoked. He said that he did not smoke much but believed that smoking was stimulating to pedestrians. He liked a good strong smoke, but not when hard pressed by opponents in a race.

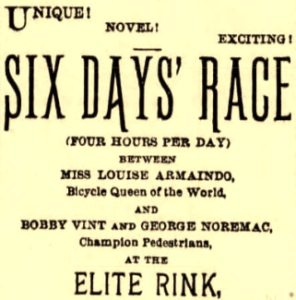

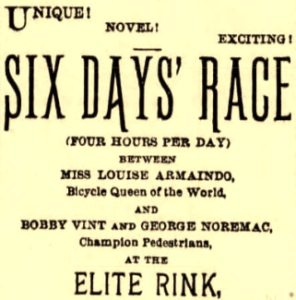

Roller skating for Six Days

In 1885, the first six-day roller-skating race was held in Madison Square Garden while Noremac was walking circles in his saloon. The event was popular, but not a financial success and the winner, 18-year-old William Donovan, a newsboy from Elmira, New York, who reached 1,092 miles, died a couple months later from pneumonia.

Competitions during 1887-1888

Noremac took six months off, returning in 1886, competing each month in the upper Midwest. He would win in the money but now with few wins. In February 1887, in Easton, Pennsylvania, he broke a 72-hour six-day record by a mile, reaching 415 miles. He would hold that record until broken by Peter Golden in 1888 with 430 miles.

In February 1888, he competed in a major six-day race in Madison Square Garden with 24 runners. “The buxom wife of George Noremac, who has been in attendance on her plucky husband all through the race, has established herself at housekeeping In a sort of front wing to his booth.” When a bagpiper played, Noremac ran with a smile on his face. James Albert broke the six-day world record in 621 miles. Noremac reached 525 miles, finishing in eighth place, and winning $240 for all his work.

Runners Against Cyclist

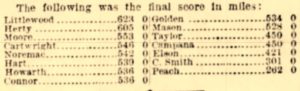

George Littlewood’s Historic World Record

Moved to Philadelphia

By late 1889, he discovered that maintaining championship form was becoming harder. He admitted he was not in top condition, and it showed when he finished last with only 212 miles in 72-hour six-day race in Pittsburgh. Any winnings earned were far less than in prior years and his backers lost large amounts of money.

But Noremac did not give up. His wife helped crewed him in at his races, watching her plodding husband with constant and anxious eyes. “His wife, a large, buxom woman, is his trainer and attendant, and there is no more faithful or skillful one in the business.” Finally, in March 1890, in Detroit, he got back into his groove and placed second in a six-day race with 500 miles winning $424.

But at age 37, he was a mid-pack runner and just couldn’t break into winning the big races again. He battled injury, causing him to skip months of races. It was said of him, “He can be depended upon to stay on the track until the walk is over, but not as a rule a first prize winner, but he usually wins some prize.”

In March 1891, he ran in a six-day race in Madison Square Garden with 43 entrants. It was billed as, “A determined attempt to revive the interest in pedestrianism.” He reached 525 miles, qualifying him for a share of the profits. It was at least the 12th time in his career that he exceeded 500 miles in a six-day race. After the race, it was called, “The greatest fizzle of a six day walk that was ever held. It has been a most dismal failure from the standpoint of sport, and its promoters and everybody connected with the affair have lost money.”

Comeback Attempt

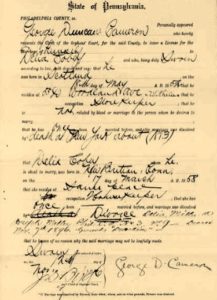

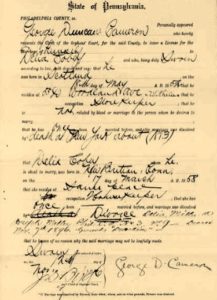

Noremac’s last truly competitive six-day race was in May 1891 in Madison Square Garden when at the age of 39, he finished in sixth, with 525 miles. Finding it difficult to win money, Noremac went into retirement as fewer six-day races were being held. In 1896, he married for the third time, Delia (Cobey) Miller (1859-) in Philadelphia. She had recently divorced her husband. They stayed together for the rest of his life.

In May 1899, at the age of 47, Noremac was determined to compete again as six-day races were trying to make a comeback. He competed in a 72-hour, six-day race in New York City at the Grand Central Palace on a track 13 laps to a mile. He was the old-timer in the race. He came in last place. Two doctors with the Board of Health visited and threatened to take all the old runners off the track. He continued to try to compete but always finished in the back. The new Mrs. Noremac would help during the races. His comeback attempt was partially successful in 1901 at the age of 49 when he finished fourth at a six-day race in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania with 414 miles, winning him “an immense bouquet of chrysanthemums.”

It can be said that Noremac never fulling retired from Pedestrianism, the sport retired on him. He kept competing to the bitter end in 1903 until most competitions were discontinued due to lack of interest and local laws put in against such events. His last known true race was a relay race in November 1903, when he was 51 years old. He teamed up with fellow old-timer, Sammy Day in a six-day race at the Industrial Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on track measuring 17 laps to a mile. They dropped out on the second day.

Running Finally Over

In January 1908, when Noremac was 56, Akron Ohio, thought it would be fun to put on a six-day race and invited many of the aging pedestrians for a nostalgic race. Large crowds came out. “Noremac appears periodically on the track and adds to the amusement of the crowds. The shrewd little Scotman’s observations on his competitors have proved an unfailing source of amusement to the watchers.” He came in last with 73 miles, only able to walk a few days and not truly trying.

George Noremac was perhaps the most prolific six-day ultrarunner in history. It is estimated that he finished about 80 six days races, reaching more than 300 miles in nearly all of them, and exceeding 500 miles in sixteen of them. In all, his career miles in races exceeded 30,000 miles, spanning 25 years

Noremac was buried in Arlington Cemetery in Philadelphia, sadly not next to his murdered first wife, Elizabeth, buried and forgotten in New York City.

Ultrarunning Stranger Things Series:

- Part 1 – Two Tales

- Part 2 – Hallucinations

- Part 3 – Sickness and Death

- Part 4 – Race Disruptions

- Part 5 – Steve Brodie – New York Newsboy

- Part 6 – Fraud, Theft, and Nuisance

- Part 7 – The Murder of Alice Robison

- Part 8 – Love Scandals

- Part 9 – Corruption and Bribes

- Part 10 – Richard Lacouse – Scoundrel

- Part 11 – Arrests

- Part 12 – George Noremac and Murder

- Part 13 – Strange and Tragic

Sources:

- P.S. Marshal, King of the Peds

- P.S. Marshal, GEORGE NOREMAC: The Original “Flying Scotsman!”

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Feb 24, 1865

- North British Daily Mail (Lanarkshire, Scotland), Aug 20, 1877

- New York Times (New York), Jun 16, 1879, Feb 27, 1882, Mar 2, Oct 29, 1882, Aug 24, 1883, May 11, 1885

- New-York Tribune (New York), Mar 5, 1882, Oct 23-28, 1882, Aug 24, 1883, Dec 2, 1888

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Jul 22, 1881, May 11, 1885

- The Brooklyn Union (Jun 16, 1879)

- The Sun (New York, New York), Dec 26, 28, 1881, Mar 1, Oct 29, 1882, Aug 24, 1883

- Aberdeen Journal (Scotland), Jul 8, 1879

- The Courier and Argus (Dundee, Scotland), Jul 15, 1879

- Sporting Life (London, England), Jan 3, 1880

- Aberdeen Herald (Scotland), May 29, 1880

- Sporting Life (London, England), Oct 6, 1880, May 31, 1881

- Glasgow Herald (Scotland), Dec 20, 1880

- North Star (Darlington, England), Jan 6, 1881

- The Evansville Journal (Indiana), May 14, 1882

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Aug 1-5, 1882

- The Penny Pater (Cincinnati, Ohio), Oct 12, 1882

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Aug 24, 1883

- The Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), May 28, 1883

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Aug 27, 1883

- The Daily Deadwood Pioneer-Times (South Dakota), Aug 28, 1883

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Nov 4, 1884

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), Nov 4, 1884

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Mar 25, 1888

- Waterbury Evening Democrat (Connecticut), Oct 14, 1889

- Pittsburgh Dispatch (Pennsylvania), Dec 3, 28, 1889

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Dec 23, 1890

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Jan 11, 1891

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Mar 21, 1891

- The Los Angeles Times (California), May 13, 1899

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Nov 17, 1901

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Feb 18, 1922